Dell M. Hamilton’s work draws on not only the historical conventions of photography and performance art but also on the history of black theater, the written and oral traditions of black & Latina women writers as well as the contradiction & exuberance of drag performance. In this interview, we spoke about her practice, our current socio-political landscape, and her recent photo series: Fallen Angels: Making Sense Out of Nothing, which investigates the relationship between persona, performance, and photography through the conflation of characters inspired by Central American folklore, personal memory, and family history.

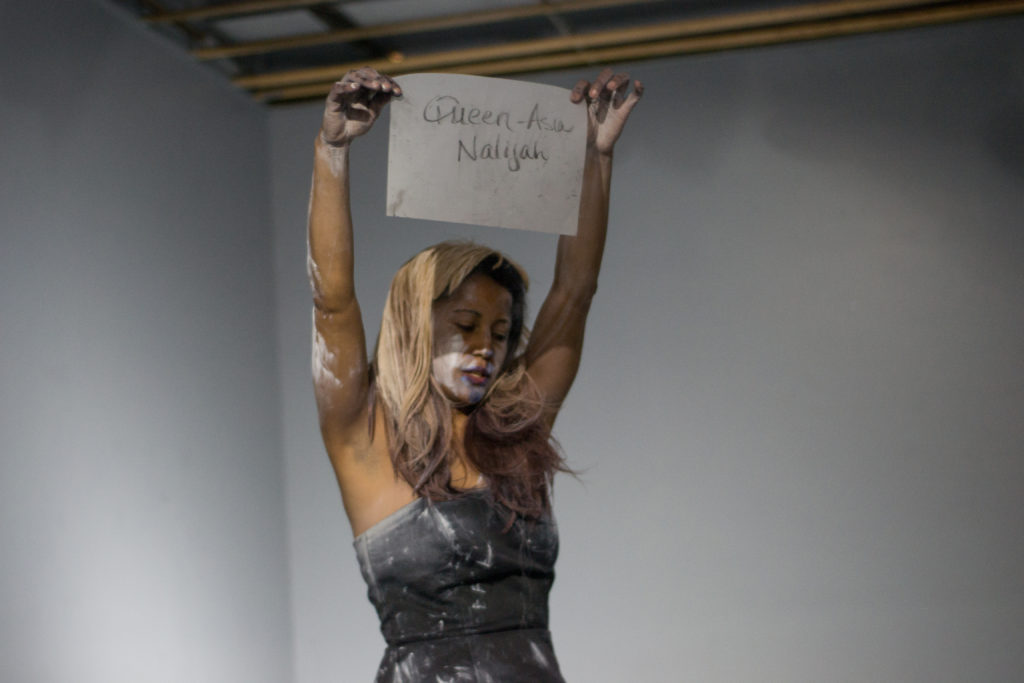

#BLACKGIRLLIT: BETWEEN LITERATURE, PERFORMANCE & MEMORY at FIVEMYLES. Photo by Tiph Browne

Silvi Naci: I know political and social fragmentations currently happening in the U.S. for the last year and especially last few months have hit you really hard; how does your work (visual, writing, curating) confront these issues? How do you change your tools as an artist, engage the viewer differently, and your civic engagement to your audience?

Dell M. Hamilton: Currently I’m in a moment of pause and reflection. It’s been a really crazy year, a really irrational, erratic year. Not just in the sense of the election but it’s a year where I have experienced a lot of death - with family members, mentors, colleagues, all of them in different stages of their lives, with so much meaning, exuberance, and vibrancy to still contribute to the world. And trying to wrestle with those absences has been really difficult for me. But it seemed to me that I needed to deal with my own grief. I want to read to you briefly this passage:

"I read somewhere that we begin grieving the instant we're born because we've given up the only tangible security we can ever have. That is to say that loss, fear, and anger - major components of grief - are intended to be ever-present in human life. Depression evolves when we stop expressing our genuine emotions. Perhaps that occurs as we learn to put on a happy face to please those who feed us, tickle our chin, and touch us when we look cute and happy. I freely admit that I would walk towards a happy baby, or adult faster than toward one whose screaming. And so the socialization begins. Be easy, be happy, or be rejected. Don't let others know how you see things, or how you feel, if it jeopardizes your crumbs of security. Some would rather give up expression than risk being or feeling alone." - Eric Maisel

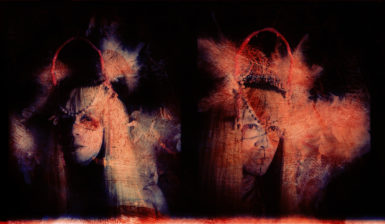

Fallen Angels #3.

I refer to that passage partly to grapple with my sense of aloneness and also knowing that ways I’ve gotten through previous bouts of moral, personal or existential crises have been to be in community. But yes again, I am in a moment of deep pause and deep reflection and trying to rethink how I would reshape my practice. In 2016, at a talk at Harvard’s Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, Tania Bruguera discussed perhaps needing to shift from being an artist to being a politician (as a result of her detainment for organizing a public performance called “Tatlin’s Whisper #6” in Havana’s Plaza de la Revolucion in 2014. There’s something about that I feel is so beautiful, so brave and so courageous but at the same time reminds me of the limits of art and the limits and risks of citizenship. To me right now this is not always necessarily about possibilities but grappling with my own constraints and the constraints of our own political systems.

SN: On your first article on BR&S for (INSIDE/OUT artist residency) you write: “How do I now make sense of a country whose present strauma (stress, trauma, & drama) is as anti-Semitic, anti-immigrant, anti-indigenous, Islamophobic, homophobic, oppressive, war-mongering and misogynistic as the one into which I have been born and willingly make art about?”

Now that the truth is out, the veil has been lifted in our society, how do you continue to make work? What conversations are you engaged in, choose to be engaged in, and how do you see your work changing or shifting?

#BLACKGIRLLIT: BETWEEN LITERATURE, PERFORMANCE & MEMORY at FIVEMYLES. Photo by Tiph Browne

DMH: Checking in with colleagues, seeing family, I am thinking a lot about the concreteness of what I can do in the now. This includes recently meeting with two of my mentors, who are a married couple, a minister and a sociologist. There’s a kind of radical acceptance in knowing that we can really push the train forward. And there are moments in which the power structures that are already in place, and human beings who are not willing to give up power and are not willing to share power and co-engage are going to push back and they are going to push really, really hard. So Trumpism happens as a result of President Obama but in spite of Obama. That is what I’m thinking about and relying upon seasoned mentors and activists who have great faith in the fact that human beings always have the ability to transform their situations and to speculate for a future world that includes all of us. Those are the things I am trying to hold onto - a faith in humanity. Not necessarily the systems, but in how human beings in our day-to-day interactions can enact a level of kindness, support, and agency.

SN: Can you speak a bit about the personas you investigate in the series Fallen Angels: Making Sense Out of Nothing?

DMH: I began developing the Fallen Angels series during the Boston Snowpocalypse (winter of 2014-2015). Something I am always thinking about is the limits of performance and the limits of photography. And so one of the tensions that I am really struck by, which I know exists but I still have to wrestle with, is that when I do a performance, I experience it in a particular way and when I get the documentation something else has transpired. Because whoever is documenting sees what they want to see. It occurred to me that I am never going to solve this problem because I can’t control everything, and perhaps don’t even want to.

I wanted to retreat back into imagination, in my studio space, retreat back into myself and allow myself to collapse these boundaries between photography, performance, and personas. To me, personas are very useful as they have so much elasticity, and we can just make them up. Each of us is performing some part of ourselves or invented thing all the time. I was thinking of my own need to still make pictures even though I make live art. I need to make pictures because I need to make them. There are images in my head that I need to fix on a surface. So I am thinking about film as a skin, canvas, tabula rasa, and surface for me to project onto.

Fallen Angels Reina #6.

These characters are loosely based on my mom and her sisters. I come from a highly matriarchal family, where the women are in charge of everything. The men are there but they are not really consulted. Their job is to sit back and let the women take care of what they need to do.

As a young girl, I thought of with my mom and my aunts, they seemed like superheroes to me. There were so many of them, and I often never knew what they wanted or expected. But now as an adult, I am thinking about inter-generational memory and the processes between girlhood to womanhood and adulthood. How so much of that is rendered through images and touch, also oral history and stories that are told and not told. I wanted to see if I could get at some of these personalities and if I could build these characters through these performances (and images). So the personas are disguises for my mom and my aunts in different phases of their lives.

Fallen Angels Reina #7

I feel I am in the beginning of the series and thinking about how to build a narrative with these images, and what would the actions and the gestures mean; what happens when there’s more than one character in the frame? What happens when it becomes a video piece and there is dialogue?

SN: At the Gertrude lecture, artist Jeanne Simms brought up the idea of whiteness in regards to the photographs, your light skin in the work, and the angles in regards to Christianity. What does that ‘whiteness’ mean to you and were you thinking of white face while making the work?

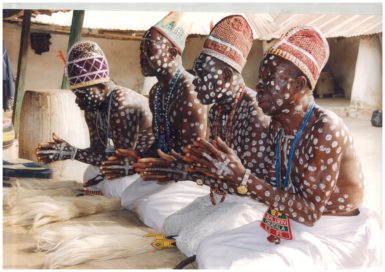

Photo by Esteban Felix.

DMH: In an American context, yes that’s one way to think about whiteness because everything in the U.S. is about blackness or whiteness. But it’s actually a mixture of white body paint and cascarilla- (egg white paste). In Afro-Cuban and West African religious traditions (where the use of body paint is widespread), so the white is not about whiteness as a racial construct, but I have also left that open for viewers to think about. However, I was more thinking about a syncretism that’s related to Christianity but that which is looking at both side of the Atlantic. It was also about white light as a force field to put around yourself. What I know about myself is that I’m a sponge, and there’s something about covering yourself in white light in order to keep out the darkness. The use of white body paint was also influenced by my incorporation of imagery from ‘Day of the Dead/All Saints Day gatherings.

SMITHSONIAN NATIONAL PORTRAIT GALLERY with MARIA MAGDALENA CAMPOS-PONS & NEIL LEONARD. Photo by Paul Morigi

SN: Can you speak of the influence the women and mentors in your life have had in your artistic practice?

DMH: For me, it’s been Carrie Mae Weems, Maria Magdalena Campos-Pons, Deborah Willis, Cheryl Finley, they are all four amazing women who told me, all in different ways, that I could do this. I didn’t grow up thinking that I would be an artist. That is not what I had in my head. Watching them work, seeing how they approach their practice, which is very much about collaboration and always about a conversation and a discourse.

SN: You became “Abraham Lincoln’ for a performance with fellow artists Maria Magdalena Campos-Pons and Neil Leonard for their project “Identified” that was part of the ‘IDENTIFY: Performance Art as Portraiture’ series at the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C. How do you think through constructing your performances in relationship to other great contemporary artists such as Campos-Pons, Deborah Willis, and Carrie Mae Weems?

DMH: When Madga [Campos-Pons] approached me about the performance in Washington, D.C., she wanted to think about Lincoln’s impact on the Caribbean, in particularly because the top level of the museum has a room in which Lincoln held his inauguration dinner. Because Magda is Afro-Cuban, she is always trying to make these larger connections. It was an interesting concept and I didn’t know what Lincoln’s impact on the Caribbean was.

I tried to think about the fact that, once emancipation happened in the United States, it signaled to other countries in the Caribbean that emancipation was possible and the abolition of slavery was possible, which is meaningful simply because slavery wasn’t abolished in Cuba for example until 1886, (slavery was abolished in the U.S. in 1865). For Madga’s family, those stories are intact, which is not necessarily the case for my family, who has roots in Honduras, Belize and the Caribbean.

SMITHSONIAN NATIONAL PORTRAIT GALLERY with MARIA MAGDALENA CAMPOS-PONS & NEIL LEONARD. Photo by Paul Morigi

I learned that during the Civil War, Lincoln had a contingency plan, and started to think about what would happen if the North didn’t win and African Americans could not ever find emancipation, liberation, and equality. What would happen then? He met with a retinue of African American leaders and thought about a contingency plan in moving black folks to British Honduras, (which is Belize now), and found this historical document developed by British Honduras government which was handed out in encampments. So once runaway slaves made it to union army camps they were considered ‘contraband’, so they were in this middle space between slavery and citizenship. But at that moment members of the British Honduras Company would hand out these pamphlets at encampments, so I thought about handing out these pamphlets and doing the Gettysburg Address, and how would I dress up and queer the performance to allow for this other narrative to be brought to the forefront.

SN: There’s a duality in your previous work (Emulsions in Departure series). The images could pass for beautiful photographs but the process is so much more involved. I think about your work and your civil duty – as a self-described “political junkie.” How you mesh your aesthetic with that of journalistic or news images?

DMH: I’ve been watching the news, reading the newspapers, arguing with my Mom and Dad, doing and thinking about politics since I was a kid. This makes me think a lot about the limits of my own work. I can do everything that I can to try and be ethical and engaged and there’s still so much I cannot do. Like if it was up to me, Trump would not be in office. I would just wave my magic wand. Like the character Reina in the photographs, she lays waste to whoever is not suppose to be there; all three angels in ‘Fallen Angels’ are revenge angels and are really preoccupied with getting justice. But I can’t do that. I am thinking a lot about continuing to talk with folks and try to listen, to understand what exactly are the origins of the ‘alt right’; ‘white nationalism’ or ‘white nativism’ (such as re-reading the work of scholars Richard Dyer and Robyn Wiegman). But there is also a point in which you have to walk away from your abuser and not engage at all.

However, I’m in a place where I am not willing to give up. I can’t give up, because if I do give up then I might as well not get out of bed.

Obatala Priests in Nigeria.

SN: During your Samsøñ/SubSamsøñ residency you had many great studio visits, can you share a great advice given from a curator?

DHM: What stood out to me was that people wanted to come and talk with me about my work. I thought that was fascinating. This was important because I’ve been trying to figure out my art practice, and myself for a long time and the fact that people were paying attention, I have so much gratitude for that.

What Liz Munsell (MFA/Boston, Assistant Curator, Contemporary Art and Special Initiatives) reminded me about was the physicality of my work and how the work could move into sculpture, installation and still be fully engaged, activated by performance & live art. As Carrie Mae Weems says: What does the work want, what does it need and how can I get out of the way, so it can do what it needs to do because it has to live outside of you. As Fred Wilson has also said, the work will probably have a better life than I do. It gets to be collected and live in museums and I just go back to my regular life.

SN: Ode to Hans Ulrich Obrist, do you have any unrealized projects?

DHM: Yes. I want to write a play, and I want it to be a conversation between my mom, my grandmother, great-grandmother and Zora Neale Hurston.

––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Dell M. Hamilton's artist talks, solo performances, scholarly lectures, and collaborative performances have been presented to a wide variety of audiences in Boston and New York as well as in France, Italy and Chile. Born in Spanish Harlem (New York City), and with ancestral roots in Belize, Honduras and the Caribbean, her practice wrestles with the social and geopolitical constructions of memory, gender, race, language and history through the mediums of photography, video, drawing, installation and performance. To learn more about Dell’s work, please visit www.dellmhamilton.com, or follow her on Twitter and Instagram: @dellmhamilton

Hamilton will be presenting a performance at the closing reception of the Photographic Resource Center's exhibition: Race, Love, & Labor curated by Sarah Lewis on January 26.

STAND UP – Women* You Should Know: is an interview and lecture series program where women* of various marginalized cultures come together to share conversations about artistic processes, education, community, and contemporary art practices. [Women*: open to anyone who identifies with this word.]

References:

- THE VAN GOGH BLUES, The Creative Person's Path through Depression, 2002 Eric Maisel

- Carrie Mae Weems, I Once Knew a Girl, The Cooper Gallery, Harvard

- IDENTIFY: Performance Art as Portraiture / María Magdalena Campos-Pons

- Deborah Willis

- Cheryl Finley

- Fred Wilson