Since the ascendance of the term “identity politics” into mainstream discourse in the 1980s, the debate, vitriol, and confusion over what it means to acknowledge our unique subject-positions in the world is enough to drive one away from using the term at all. But the moment we stop trying to acknowledge the politics of our identities we risk reducing our natural variation to a single level, an operation that has historically never ended well. As a cis man, I have been slow to seek out the vocabulary for understanding nonbinary gender and gender-nonconforming identities, let alone the tools to discuss art that responds to those identities.[1] My expectation of feeling clueless at the opening of trans/draw, a group exhibition in Cambridge of recent work by area trans artists, melted away as I walked in and began discussing the installation with artists who patiently filled me in when I was unclear about the terminology they used.

Organized by BLAA (Boston LGBTQIA Artist Alliance), trans/draw features sixteen works by twelve artists. The exhibition was conceived by Boston-based artist Lenny Schnier and juried by Brooklyn-based artist Cobi Moules. Like the participating artists, Schnier and Moules are trans, as are most of those involved in the show’s organization. The venue, non-profit Gallery 263, is a cozy space with windows on two of its four walls. Not far from Central Square, it is exposed to the street, but on this occasion felt like a retreat, a safe space for artists and viewers. At the exhibition’s opening, a community coalesced around art in a humble and generous way and, I suppose on account of the community’s intimacy and political involvement, one woman leaned in to remark, “this kind of event could only happen in a city like Boston.”

Catherine Graffam, Please, Tell Us More, graphite, acrylic and acetate, 16"x20", 2016. Photo courtesy of BLAA.

Co-curator Lenny Schnier considers the practice of drawing emancipatory, immediate, and deeply personal.[2] In the context of the present show, drawing is not limited by medium, but rather taken as an attitude toward mark making. The works range from graphite on paper and paint on canvas, to film, zines, mobiles, and a conceptual installation. Some of the works are intensely labored, such as the uncanny tufts of hair on the lower buttocks of A.B. Miner’s graphite drawing Bad Fit (2016), while others, such as Schnier’s coiffed mannequin head (Untitled (pink head), 2016), engage with readymade materials. Chih Ching (Jill) Ma punctured handmade paper to look like wounded flesh in Peels and Heals Part I and II (2016) and on an adjacent, similarly distressed sheet, sutured the wounds with thread, conjuring a sensation of sharp pain in the viscera.

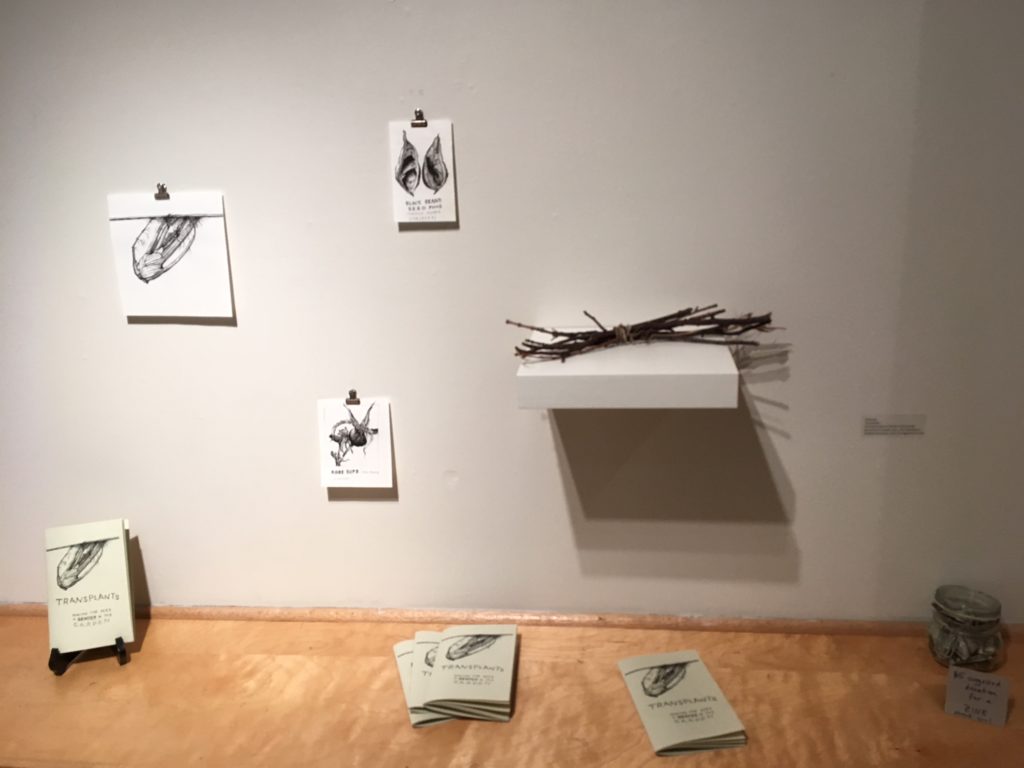

The works in trans/draw are as much about drawing as they are about a lifetime of experiences seen from a particular subjectivity—one that indefatigably defies norms and is perpetually demanded to explain, deny, and change itself. Eli Brown’s installation, Transplants: Sowing the Seeds of Gender in the Garden (2013), uses plant species that evoke human reproductive organs or change gender as a way to frame trans identities and terminology. Surrounded by Brown’s informative zines, a small bundle of sticks rests on a ledge at eye level (historically, “fagot” refers to the kindling used to burn heretics at the stake). Humbling and disquieting, Transplants is a forceful reminder that identity may be natural to us individually but is nevertheless also imposed and distorted by external forces. Going beyond the hackneyed distinction of “nature versus nurture,” the work shows how mutually-inflecting the biological and cultural domains are on the development of identity. While the natural world may not always be an inspiration for tolerance, it is telling that the scientific term for flowers with male and female reproductive parts is “perfect.”

Eli Brown, Transplants: Sowing the Seeds of Gender in the Garden. Photo courtesy of the author.

Schnier comments that trans/draw is necessary because there are so few spaces where trans artists and thinkers have centralized voices and a platform to commiserate over shared joys, desires, and challenges. This is changing with initiatives by institutions such as The Museum of Transgender Hirstory & Art at ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives in Los Angeles and the Leslie-Lohman Museum for Gay and Lesbian Art in New York, to name just two of the most prominent. Within the Boston area, trans/draw stakes out a space for work by trans artists that is explicitly separate from other contemporary art. In our present moment, grouping art under the rubric of gender nonconforming identity is a vital corrective to centuries of art devoted largely to the depiction of cis males and females, and to expressions (figurative or abstract) of those subjects’ experiences of the world. Aesthetic ideals held by some members of the trans community are still considered deviant within cis-dominant culture and it is imperative that we have opportunities to see those ideals expressed as powerfully and collectively as in trans/draw.

An exhibition that unites artworks based on one aspect of their makers’ identities is sometimes the first step toward acknowledging and celebrating them in broader-themed contexts. Extending Eli Brown’s botanical metaphors, we might see artistic, national, ethnic, and gender identities as elements of an ecosystem. When we realize how one has been constituted—through racism, misogyny, class, etc.—the others begin to shift as well. Foregrounding the trans in trans/draw did not obscure the artists’ identities as artists, but rather put that more historically-stable identity into a setting in which we can learn something new about what it means to express oneself through making and looking at art.

trans/draw is on view through December 11 at Gallery 263.

[1] On terminology: Cisgender, often abbreviated “cis,” describes individuals whose gender identity conforms exclusively to their assigned birth sex (male, female, or intersex), while transgender, or “trans,” refers to a gender identification other than one’s biological sex assigned at birth. Gender nonconformity describes behaviors and interests other than those considered culturally typical of an individual’s assigned sex. Nonbinary gender and gender fluidity describe identities and behaviors that exist on a spectrum extending beyond female and male, and which are not necessarily fixed. Neither cis nor trans identities necessarily denote a specific sexual orientation, hormonal makeup, physical anatomy, or appearance. Gender identity is an internal matter that may take any number of external manifestations. Transgender should not be confused with transsexual, a term used to describe an individual who has undergone a hormonal or surgical transition from one gender to another.

[2] I thank Lenny Schnier for taking the time to speak with me about the exhibition on November 21, 2016 from their office at the Institute of Contemporary Art/Boston. References to Schnier derive from that conversation.

1 Comment

Very cool!