Pregnancy and parenting can create serious changes to an artist’s process. As installation maestro Sarah Sze elaborated on a 2012 exhibit in London: “The pieces in this show appear to measure space, or time, and now that I have two children, time is more significant. It has more weight.”

Those exact themes of time, space, weight, measurement, and parenthood also appear in Anna Shapiro’s Kerfuffle, her latest body of works both flat and sculptural, on view at AS220 Project Space. Since giving birth to her daughter two and a half years ago, the Providence artist says “the amount of time I can spend in the studio is definitely more fragmented.”

Such time constraints have considerably affected Shapiro’s practice. Throughout her career Shapiro has oscillated between hard and soft, opting for iron, steel, plaster, yarn, collage, thread, paint. Postpartum life has nudged Shapiro into using more accommodating media, enlisting allies both pliable and firm, with crochet especially prominent. There’s material continuity with her older work, but the motifs here are less acid and more plush.

“My imagery before was very aggressive,” Shapiro says, referring to the firearms and teapots she depicted earlier in the decade. “I lost that barb. The edge is still there…like the humor and the provocativeness, but I’m not interested in presenting the violence in such an explicit way.”

The ecosystem of curiosities in Kerfuffle derives from the everyday realities of parenting. The work has “become more sophisticated…by being more juvenile,” Shapiro says. One example is Little Urchin, in which cast iron bottle nipples protrude from a nest of colorfully polka-dotted fabric. Reflecting on the piece, Shapiro asks, “What happens when time is not linear, when it’s circular?”

The omnipresence of a schedule (and the resulting circularity) in Shapiro’s life informs work-on-paper like Rounding It Out and I Couldn’t Fit You In, both of which serve as calendric grids, with X’s, dots and clocklike marks reiterated over and over. The temporality they record is not something contiguous but recurring. These pieces suggest a record of parenting’s numerous tasks: diaper changes, feedings, pacifying tears.

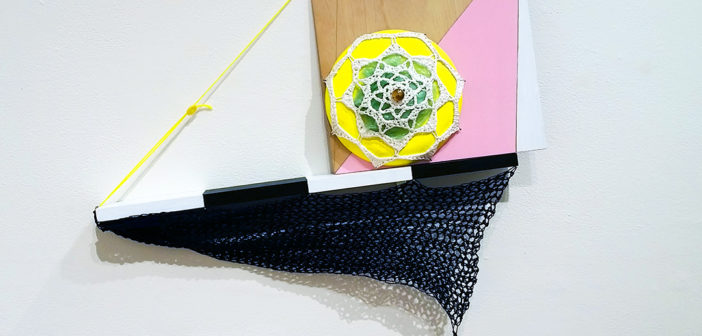

To match the repetitiveness of these actions, the paper is often not an uninterrupted sheet but instead, tiny squares queued, stacked and sewn together. These stitched paintings tally time, while the show’s sculptures measure space, like NoNu, which extends a wooden plank toward the viewer. A pink balloon levitates above the lumber, shielded by a yellow crocheted doily in a peculiarly mammary arrangement.

To match the repetitiveness of these actions, the paper is often not an uninterrupted sheet but instead, tiny squares queued, stacked and sewn together. These stitched paintings tally time, while the show’s sculptures measure space, like NoNu, which extends a wooden plank toward the viewer. A pink balloon levitates above the lumber, shielded by a yellow crocheted doily in a peculiarly mammary arrangement.

This diversity of matter, and its subsequent fusion, is salient in Kerfuffle. One of the standout pieces is Kerfuffle #1:30x, a crocheted, organismic form stuffed with newspaper and adorned with caps recycled from pouches of baby food. Like the twine cocoons of Judith Scott, the piece binds varying substances into a new entity. The individual components are not entirely lost, but their singular identities seem less important against the lumpy, dark majesty of the whole.

“These beginnings are small but I hope they become wonderfully and perversely big!” Shapiro writes in her artist’s statement. This attitude might be contextualized by turning to Kay Hayunani Trask's Eros and Power, in which the author injects the Freudian concept of Eros (the life instincts) with a dose of radical feminist theory. Trask reenvisions this “feminist Eros” as “consciously ‘timeless,’ literally reclaiming time by uncovering repression” and prioritizing “human relationship over structure, ideology, and aggression.” The feminist Eros opposes “the false separation of mind and body” and “patriarchal values of polarization and separation.”

In her statement, Shapiro poses her new work as “abstract, pre-verbal and post-theoretical,” a “collective politic of mind, body, and material”—an apt realization of the feminist Eros Trask describes.

Trask finds that once Eros is no longer “misconstrued as purely sexual,” the “true pursuit of women’s deepest erotic knowledge,” such as the mother-child bond, might begin. Kerfuffle seemingly emerges from this well of knowledge, acknowledging the mother-daughter relation as an earnest process of shared growth. Shapiro wants to include her daughter in the making process. Her babe’s influence has not gone unabsorbed; the many circles in Kerfuffle were culled from her daughter’s drawings. “I feel like I’m going back to kindergarten,” Shapiro says.

She eagerly applies the feminist label to her work. She sees fiber art as a suitable vessel for not only feminism but the concerns of any marginalized group, citing Nick Cave as a strong example of the medium’s potential for social consciousness.

“That’s what feminism to me is about,” Shapiro says. “It’s women’s issues, it’s cultural issues, it’s social issues, it’s class issues, race issues—it’s all of that stuff.”

“It's intersectional,” I say.

“Yes, exactly! Thank god for that word.”

She thus selects media not only out of preference but their political implications: “I choose my materials because of what they say, and how they say it and who else is saying it with me.”

For Shapiro, that “who else” includes artists like Forcefield, Sheila Pepe, Jessica Stockholder and Richard Tuttle. “I really love that lineage of art history, and I’m glad to insert myself into it,” she says. With these artists, Shapiro shares a purposeful retooling of craft into ‘fine art,’ challenging the monopoly of more traditional genres like painting. As Trask’s Eros upends patriarchal structures, so too is there an anarchistic sentiment to the use of craft media and methods in the upper spheres of fine art. Said Pepe of one installation: “It is definitely like honoring the crafts of the mothers.” She sees her work as homing in on “systems of power in art and education.”

For Shapiro, that “who else” includes artists like Forcefield, Sheila Pepe, Jessica Stockholder and Richard Tuttle. “I really love that lineage of art history, and I’m glad to insert myself into it,” she says. With these artists, Shapiro shares a purposeful retooling of craft into ‘fine art,’ challenging the monopoly of more traditional genres like painting. As Trask’s Eros upends patriarchal structures, so too is there an anarchistic sentiment to the use of craft media and methods in the upper spheres of fine art. Said Pepe of one installation: “It is definitely like honoring the crafts of the mothers.” She sees her work as homing in on “systems of power in art and education.”

Recent years have seen a warm institutional reception for the soft arts. One of the more memorable efforts is the Institute of Contemporary Art/Boston’s 2014 exhibit “Fiber: Sculpture 1960—present.” Fifty works by 34 artists filled the ICA in an exhibit that was billed as “the first…in 40 years to examine the development of abstraction and dimensionality in fiber art.” (Soft Power, on view through January 16, is an abbreviated survey of the ICA’s supple acquisitions, including a Soundsuit by Cave.)

Socially conscious, materially odd art, however, does not exactly equal salability: “If you think about collectors...there’s lots of people who don’t really want crocheted, whimsical things that stick out to their space that they bump into in their house. They want something that fits really nicely on their wall or desk or something,” Shapiro says.

She acknowledges that cast iron, another of her favorite media, “earns respect” in a way that whimsical, “wimpier” materials do not. The heftiness of metal and the intensive process it requires imply a greater potential for profundity—but only if one equates weightiness with erudition.

Weightlessness poses another kind of knowledge. Shapiro’s sculptures resist the idea that insight might only be gleaned from transcendent moments. Awareness might not arrive in a flash of epiphany, but instead the simple acts of care and companionship between parent and child. Shapiro’s work thus acquires a meditative quality, but her results are closer to a koan than an untroubled mind.

Pieces of the quotidian pile like laundry and assert themselves anew. The familiar becomes strange, and the routine is inverted to reveal its squishy, confused insides—a visual imagining of the exhibit’s colorful title. What exactly is a ‘kerfuffle’ anyway? The word probably derives in part from the Scots ‘fuffle,’ meaning ‘disorder.’ Shapiro eschews safety and predictability here to indulge this disorder. From bedlam, she achieves something amusing, defiant, relatable and uproariously fun to observe. Parenthood can be chaos, but there is certainly wisdom in its fractured time.