In a recent conversation with Amy Sillman at the opening of Leidy Churchman’s provocative solo show, Lazy River, at the Boston University Art Gallery, I asked Sillman about the state of painting. In 2011, Artforum considered the "The Ab-Ex Effect," thereby attempting to take the pulse of a simultaneously revered and reviled hallmark of modernism in the visual arts. Where had painting come since then? It was a question that had plagued me ever since my first encounter with Nicole Eisenman’s paintings, prints, and sculptures.1 Eisenman’s investment in art history, when combined with her penchant for absurdity and subversion, seemed to upend everything I knew about contemporary art. The same shock occurred when I thought about Sillman and her inscrutable mixture of pigment and perversion—and iPhones. With Amy Sillman: one lump or two opening at the Institute of Contemporary Arts, Boston, and Nicole Eisenman appearing in both the 2013 Carnegie International and Nicole Eisenman: In Love with My Nemesis at the Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis in 2014, it seems that we are on the verge of a new definition of artistic practice.

I had attempted for a while to characterize this charged moment, but it was not until Sillman answered, "It’s almost a queer formalism" that I found the necessary words.2 The phrase captures something revolutionary, a sense of palpable anticipation for much-needed transition that is just around the corner. The move toward queer formalism prefigured by Sillman and Eisenman, as well as artists Elise Adibi and Leidy Churchman, cannot be fully explained in a single article or with one analytical lens. It is my hope here to offer a set of disjointed thoughts that will coalesce into a question or a basis for further investigation, but never an answer.

1. Queer formalism is a paradox. Formalism requires the centrality of an object, whereas queer rejects authorship and universal concepts. Queer subverts singularity while the medium requires it. To find meaning in the internal factors of the medium is to invest in its selfhood, its ability to signify. But isn't this what queer accomplishes? Is this not what we have fought for—the ability to express one’s self, to speak, to be legible to others as a unified agent? Queer rejects unification, however. It advocates for a "queer subject" while attacking the notion of "subjecthood." Where is the balance?

2. It is exactly in the immiscibility of the terms queer and formalism that queer formalism finds its power. Queerness "represents" an unsure mixture of singular embodiment and a passionate ownership of one’s identity with the refusal of singularity.3 So too does the medium.

3. If the medium is the "essence" of the art object, its internal logic, it becomes a sort of aesthetic identity politics. Formalism’s investment in the medium has, throughout art history, suffered from a limited historical awareness and a tendency to privilege normative patriarchal values. Clement Greenberg’s assessment of Jackson Pollock, a legacy Sillman and her contemporaries have inherited, is exemplary of the mid-century valorization of medium specificity and artistic heroism. Paint became analogous with the (straight, masculine) psyche of the artist, his authority to express himself. Hence the urgent need to move toward conceptualism and institutional critique, right?

4. Still, being an artist requires a direct engagement with a medium. I firmly believe that art is not purely a product of external constructs, no matter how forcefully (and rightfully) it has been used to expose capitalism, commodification, and institutionalized oppression. In some indefinable sense, art is resistant to the outside. We cannot escape materials, and while it should not be venerated, technical skill (or an intimate connection with one’s brush or sponge or pencil) should not be discounted as not "postmodern" enough. Likewise, we cannot escape the medium of our bodies, even as that medium has become increasingly described in terms of social construction, artifice, and performativity.

5. Queerness and the medium are thus parallel. They never meet, but the path they carve out engenders an incredibly productive landscape for discussing identity and the visual arts.

6. In working toward an understanding of queer formalism, it is essential to engage with the modes of being, description, and expression unearthed by "queer." Most obviously, it is a slur that has been "reclaimed." Some find it shamefully unspecific; others consider it beautifully and necessarily open. Queer is in-between; that goes without saying. Formalism is, in some circles, a dirty word that is reminiscent of many years of a masculinist, heteronormative tendency in modernism. Being a formalist, however, does not place anyone in danger.

7. One cannot "queer" things. No matter how fervent your search for a gay character in Othello, you are not "queering" Shakespeare. Queer is not the grafting of a theory upon an unreceptive source, and queer formalism is not the queering of formalism or the formalism of queers. Queer does not require someone to "interpret" or "find" it. But if no one does, who will?

8. Queer is not a catch-all term to rack up points for political correctness, though it does touch many more people than one might expect. It affects and engages with issues of race, class, imperialism, and politics. Its function, however, is not endless; it must be tethered somewhere. But where?

9. Queer is not something beyond gay or lesbian or transgender, nor is it more "enlightened" than the identity politics of gay liberation or second wave feminism. Queer is informed by history; it is at once conceptual and contemporary and the product of countless years of physical work. We vainly consider it a product of our present moment, but it belongs to no moment.

10. The phrase "queer community" is both necessary and deeply fraught with exclusionary tendencies. Community implies accord, and has often effaced essential differences that unwittingly perpetuate institutional biases. However, the only people who can understand a specific form of oppression are those who have lived it, and finding a community is essential for many people’s coming out process.

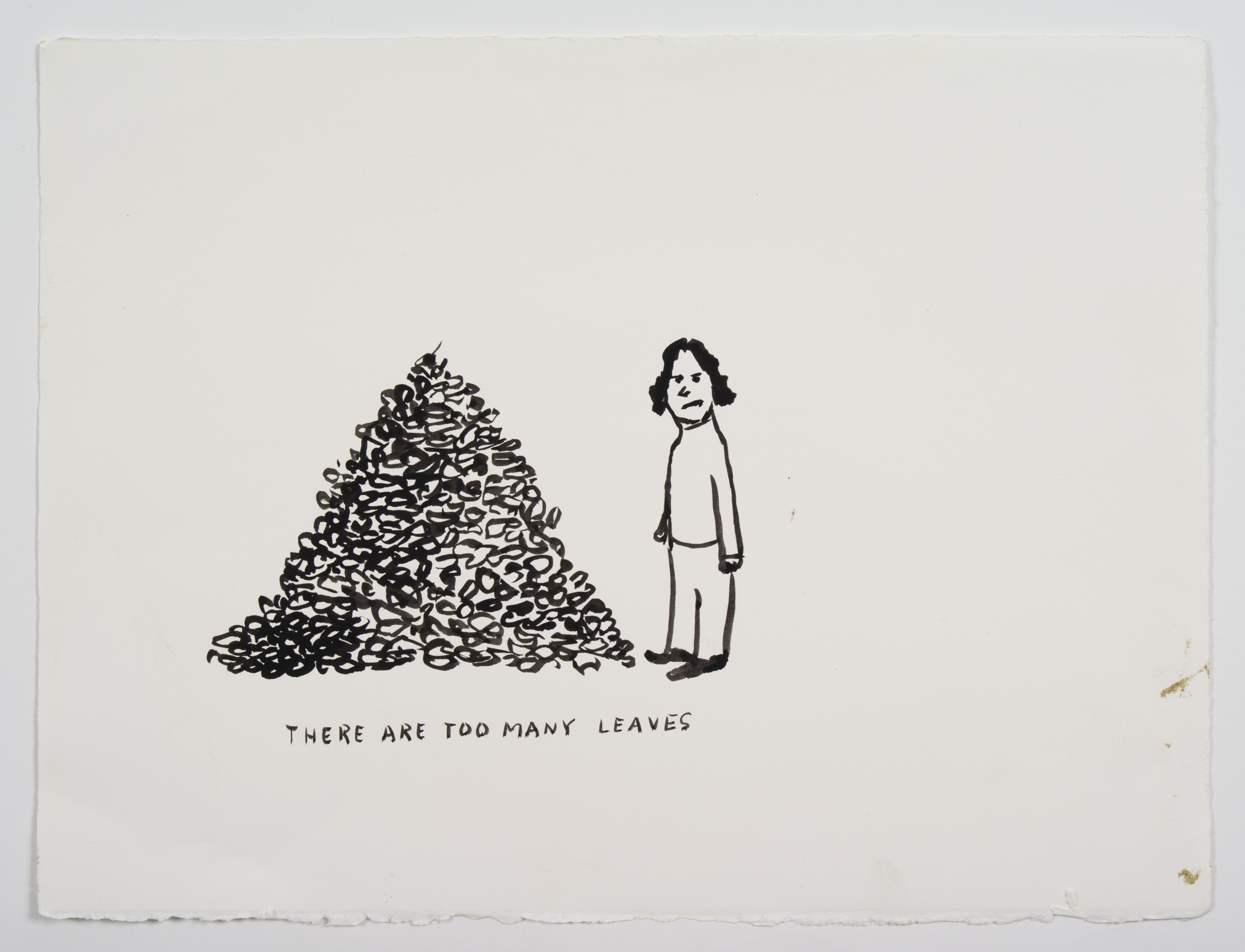

11. Eisenman’s Beer Gardens series is exemplary of queer formalism’s brand of solidarity, which she described in an interview with Brian Sholis as a diverse, anti-utopian group of misfits: "Last year, when I painted my first beer-garden scene, I immediately wanted to keep painting them, to paint them for the rest of my life…It’s where we go to socialize, to commiserate about how the world is a fucked up place. It is healthy to look at sadness in the world, and in yourself, and to dwell on it for a little while."4 Queer formalism does not exist for itself. It lives for others while retaining a precarious independence.

Nicole Eisenman, Beer Garden, 2007

Nicole Eisenman, Beer Garden, 2007

Oil on canvas, 65 x 82 in (165.1 x 208.3 cm)

Courtesy the artist and Koenig & Clinton, New York.

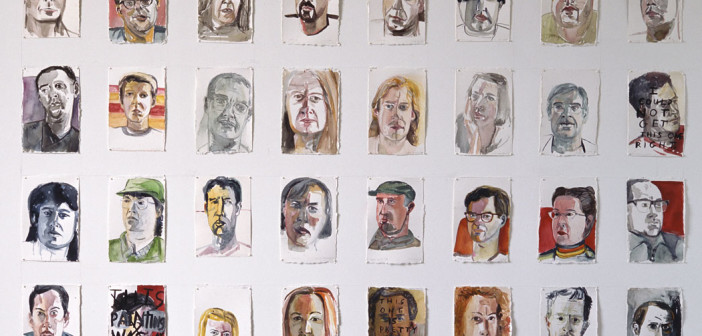

Amy Sillman, Williamsburg Portraits, 1991-92

Ink, gouache, and pencil on paper

Set of 32: 8 x 11 inches each

Courtesy of the artist and Sikkema Jenkins & Co.

Photo: John Berens

12. Queer is within and outside the masculinist, homophobic confines of our world, phenomena to which the art object is not immune. Queer requires a not-queer, or "straight," in order to exist. Homosexuality has been understood as not only a perversion, but also an inversion—what appears when you lift the mossy rock of proper social relations and look at the terrifying flora and fauna underneath. Queer defines itself in opposition to not-queer, but it need not always be in a state of antagonism.

13. Queer is not a mode of being or a means of deconstruction, and one who is queer need not constantly be in a state of rehearsing or living their sexuality. Queer is not always against; sometimes it just wants to sleep in and cuddle on a Sunday morning. Sometimes the pressure is too much to handle. It is, at times, deeply frustrating to "be" queer, a nuisance even. Must I always explain myself?

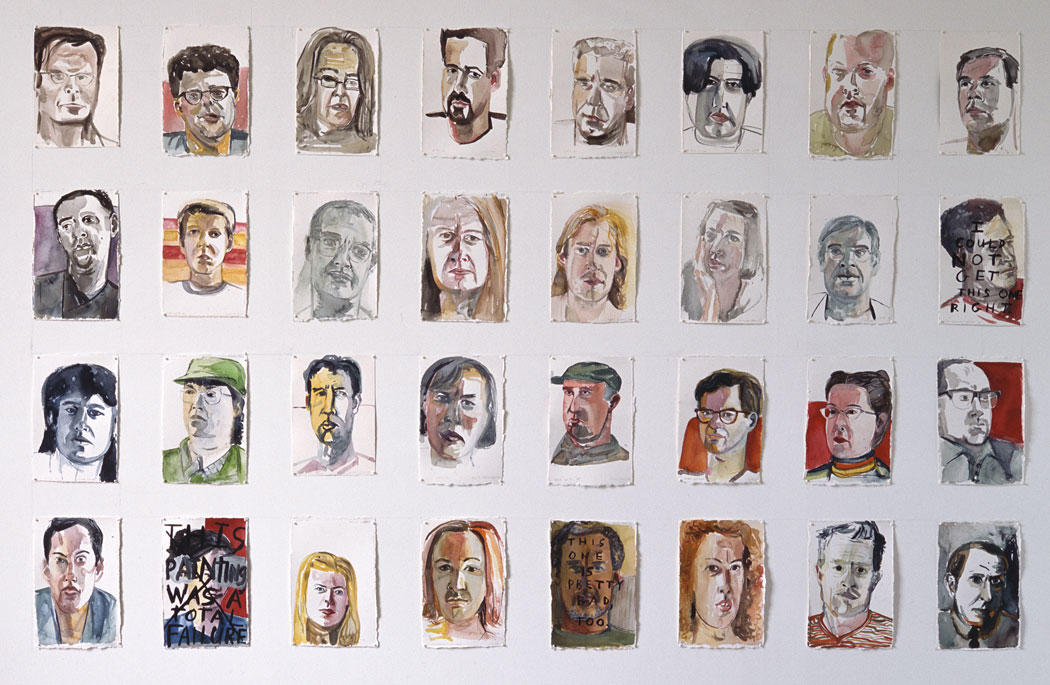

Amy Sillman, Untitled Cartoon from Amy Sillman: Visiting Artist, 2002

Ink and gouache on paper

9 1/2 x 9 3/4 inches

Courtesy of the artist and Sikkema Jenkins & Co.

Photo: John Berens

14. Queer necessitates bodies, but it also rejects the solidified nature of bodies. It insists on specificities, even as it acts as an ever-expansive force. Queer is bounded by skin, but not contained by it, like the ink, pencil, and gouache in N & O v3 (2006). Sillman’s marks bleed and seep within and among bodies, yet the image retains a particular morphology, epitomized by the architectural forms that emerge from the sitters themselves. Or maybe, conversely, the bodies originate in Sillman’s scaffolding. Sillman’s bodies somehow subsume and resist the gesture, prompting an unanswerable question - Where does the medium begin and corporeality end?

Amy Sillman, N & O v3, 2006

Ink, colored pencil and gouache on paper

17 x 14 inches

Courtesy of the artist and Sikkema Jenkins & Co.

Photo: John Berens

15. Queer is a connective force and a merciless severing, a relational action and a rejection of the world outside the self. The medium can be made to serve both purposes as well; it is both intimate and filled with lonliness. As Helen Molesworth said of the works in Amy Sillman: one lump or two, there is an element in Sillman’s work of "trying to connect with a thing that we cannot connect with."5 Sillman echoes this sentiment, "I’m so interested in things that split in two."6 Like the explosion of energy that results when atoms join or break apart, Sillman’s interest in pairs transforms the body, the gesture, and the structure of the medium into a conjoined power source. She depicts art and identity at a moment of simultaneous recombination and destruction.

16. In Shade, for example, paint becomes the body and delineates the body. True to its function, paint flows and mixes, but Sillman arrests its motion. She leaves paint destitute; its final iteration is two figures devoid of individuality. Though the figures perhaps desire to lose themselves in each other, they cannot reach across the expanse of the canvas. Sillman’s paint becomes Lot’s wife, doomed to live forever as a pillar of salt for doubting God.

Amy Sillman, Shade, 1997-98

Oil and gouache on wood

50 x 60 inches

Courtesy of the artist and Sikkema Jenkins & Co.

Photo: John Berens

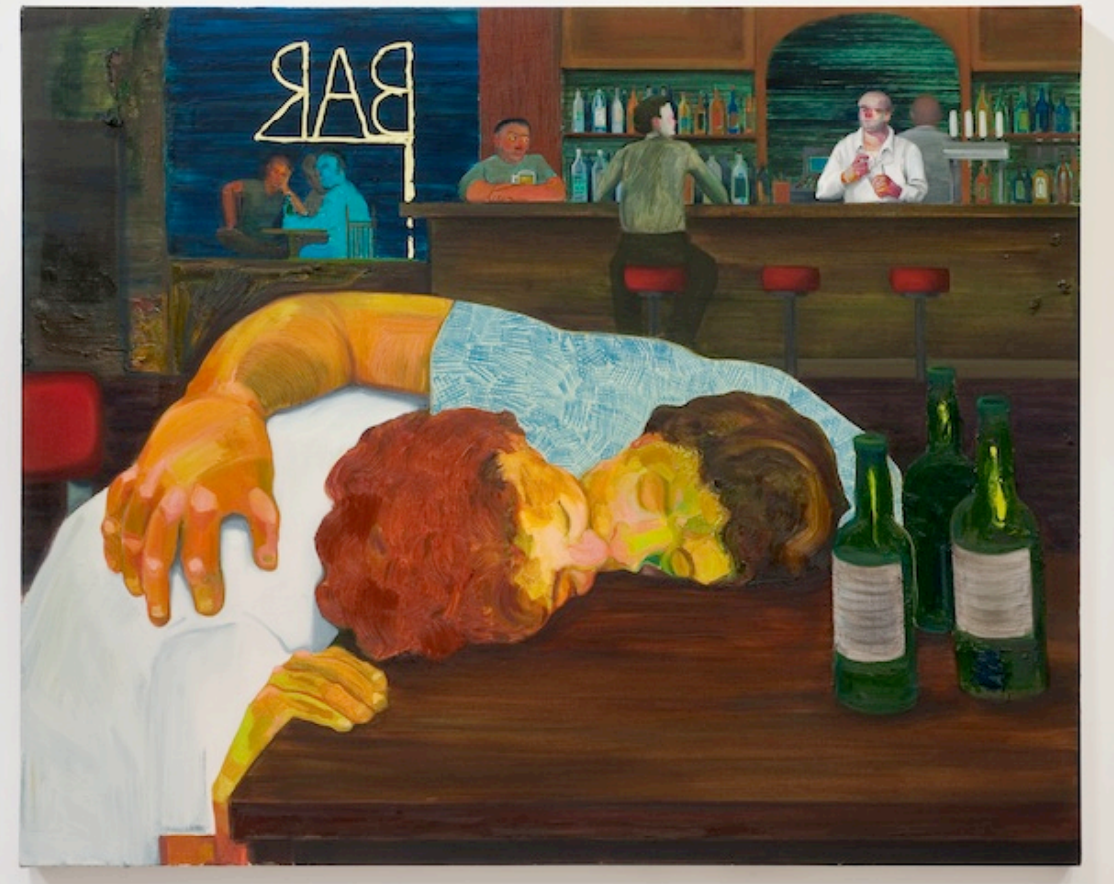

Nicole Eisenman, Sloppy Bar Room Kiss, 2011

Oil on canvas, 39 x 48 in (99.1 x 121.9 cm)

Courtesy the artist and Koenig & Clinton, New York

17. Queer can be a deeply held conviction, a passionate self-appraisal that informs one’s daily, bodily, erotic life. Still, queer expands into culture, and in Sillman’s work, it becomes implicated in the artistic process itself. Sillman drew various couples she knew and reimagined the drawings as abstract paintings on canvas, such as C (2007). C approaches the realm of concept and limitless expressivity while maintaining the outlines (not confines) of "real" bodies. As Ewa Lajer-Burcharth points out in her text to accompany Amy Sillman: one lump or two, "Through repeated re-presentation, figuration was transformed into abstraction, bodies—reduced, voided—turned into shapes, lines, colors, and forces," an operation that one can see throughout Sillman’s and Eisenman’s careers.7 Sillman presents a kind of painterly sadomasochism. Though the body is reduced to pulp, its integrity remains. The (queer) body is reincarnated as paint.

Amy Sillman, C, 2007

Oil on canvas

45 x 39 inches

Collection of Gary and Deborah Lucidon

Photo: John Berens

18. It follows that queer is both immaterial and corporeal. It is conceptual and reliant on the medium. It is deconstructive and authorial. It is the Self and the Other, together in perpetuity but not mapped onto each other. It is a multiplicity of media that lack a hierarchy, but it is not post-medium. The oeuvre of the queer formalist, like queerness itself, is invested in the interspace between and among paradoxes. Sillman has said, "I’m interested in simultaneity—the copresence of abstraction and figuration, deep space and shallow space, high and low, recognizable, literate, narrative, mythic things and dumb, vernacular, kind-of-stupid, jokey things—all these dialectics."8

19. After all these attempts at a definition of queer, can we predict what results when "queer" and "formalism" collide?

20. To begin, in the same way that queer does not require "coming out" or "identification," queer formalism need not exteriorize itself, or expose its contents to the world. It is somewhere between discovering and proclaiming itself and investing in what Lajer-Burcharth calls "intangible, unlocalizable interiority."9 What might it mean to "come out" in the medium?

21. Androgyny or fluidity cannot capture the emotional, historical, sociopolitical, and artistic plenitude of queer formalism. The term androgyny advances a monolithic vision of queerness that relies upon normative visual decidability. Queer is not a project of counting the number of figures in a work of art whose gender is indeterminate. Fluidity is as bad as androgyny when used as a weasel word to give the illusion of progressive scholarship. Queer formalism is not about scrambled gender roles. For some queer people, gender roles are central to their sexual experience. Furthermore, gender/sexual identity can be as important as life itself—trans* pioneers have taught us that. Fluidity, when used irresponsibly, can negate lived experience.

22. Assessing the sexuality of the artist is not enough to establish queer formalism, though it may be a relevant factor. Queer formalism does not only apply to "queer" artists, and it is certainly not equating art made by queer artists with "queer art." Moreover, sexuality is not something that must be constantly embodied by an artist. While it is a moral imperative to acknowledge gender and sexuality (the personal is political, and it always will be), the character of an artist must not be imprisoned by biography. One might create a work of art "as" a gay artist one day but not "as" a gay artist the next.

23. Elise Adibi, who does not identify as queer, has worked to understand, appraise, and take apart the monolithic history of the grid by assaulting it (or paying cautious homage to it?) with dripped paint, plant oils, and rabbit skin glue. She combines long-entrenched modernist discourses, such as the expressive gesture and the determinist grid, that are as consecrated as the gender binary itself. In so doing, Adibi points to the possibility of the Self and Other coming together without the specificities of either being extinguished. Adibi approximates a space described by Gayle Salamon in Assuming a Body: Transgender and Rhetorics of Materiality, that is, "the place where I confront the otherness of the other without annihilating or canceling that difference or replicating the other in my own image."10 Is this not a project of queer formalism?

Elise Adibi, Aromatherapy Painting, 2013

Rabbit skin glue, graphite, oil paint and blue tansy essential plant oil on canvas

20 x 20 inches

Courtesy of the artist and Churner and Churner

Photo: Heather Latham

24. Brief intermission. Is queer formalism only conceivable to queer critics? Is it morally tenable to discuss queer formalism if and only if the historian or critic is queer? I hope not. Am I only writing this because I myself am gay? I have no privileged access to issues of gender and sexuality. No one does, irrespective of one’s gender or sexual expression.

25. Queer formalism is tragic and destructive and vile; it wrecks our understanding of respectability and order. It is dangerous and sexy and angry and spiteful and ridiculous. In the July 3, 1906 edition of the Lewiston Daily Sun, the author reports on a lethal train crash:

Salisbury, Eng., July 2 — The embalmers are busy tonight and by tomorrow the majority of the bodies of the score of Americans who lost their lives in the wreck of the Plymouth express Sunday will be prepared for their return for burial in the land they so recently, in the fullness of life and hope, left . . . The inquest today was a prolonged and tedious formality . . . a strange proceeding to the many Americans present but which is thought to be due to the queer formalism that seems characteristic of such cases in this country.11

Queer formalism is exactly the opposite of formality, but it is not frivolous or secondary to "serious" criticism. All honest scholarship is based in passion, desire, rage, and obsession; it is always ready to brush with death, perhaps its own destruction. According to Bob Nickas, "Doubt, then, is one of [Sillman’s] most reliable and trusted subjects."12 This is not, however, tentativeness or timidity. Indeed, queer formalism’s insecurity is a radically courageous act, a fearless celebration of the precariousness of life. Love, bodies, paint, paper, and canvas all disintegrate only to be reborn.

26. Sillman assaults her chosen medium and its support, be it paper, ink, oil paint, canvas, or an iPhone touch screen, in order to access its internal logic or confusion. Returning to Lajer-Burcharth, who describes a series in the late 1990s and early 2000s that combines humanoid figures with abstraction, it is evident that Sillman locates this (queer) physicality within the medium itself:

Violence is implicit in both the final form of these paintings—bold, sweeping, rectilinear trajectories of chroma cutting through the representational field—and the preparatory drawings showing bodies deformed by the slashes of black ink, to say nothing of the very logic of subtraction, or evisceration, that defines the process Sillman adopted in this series.13

27. Likewise, in his video project Painting Treatments (2010), Leidy Churchman equates canvas and body bag, sculpture and corpse. For Churchman, everything is a kind of medium—skin, office folders, tree branches. Bodies and paint bleed together, at times creating a beautiful sculpture, but more often a cluttered, fecal mess. There is no room for idealism in Painting Treatments—aesthetic, sexual, or otherwise. Pollock’s immortalized ejaculatory dance becomes an unassuming display of flippant eroticism that is simultaneously arousing and sickening. Sillman recalls,

They [Churchman and his associate Anna Rosen] did excessive, polychromatic things to our bodies, like dipping a banana into a can of orchid-lavender paint and pressing it against our asses, or dragging a rake with green and brown paint in its combs across our legs, or letting chrome-yellow enamel dribble off random pieces of plywood onto the smalls of our backs, or tossing some green-gray grit on us.14

Queer formalism is messy while maintaining a perverse beauty. It acknowledges the uncertainty of artistic discourses and of life itself. It is not afraid to cry or get beat up. Like my mom always said, if you’re not bleeding, you’re fine. There’s something wonderful about queer formalism’s ability to be not fine, to hurt, to expose the abjection inherent in both the paintbrush and the body.

PAINTING TREATMENTS 2010 from Leidy Churchman on Vimeo.

28. Queer formalism understands history and pays homage to it. It has its own history; it fought for its own history, but in doing so, destroys history. Sillman evokes the legacy of camp in relation to Abstract Expressionism:

I would argue that this is because AbEx already had something to do with the politics of the body, and that it was all the more tempting once it seemed to have been shut down by its own rhetoric, rendered mythically straight and male in quotation marks. AbEx’s own deterioration into cliché was a ripe ground, a double-edged challenge that, to quote [Susan] Sontag again, "arouses a necessary sympathy." AbEx was like a big old straight guy who had gone gay.15

29. Eisenman, also deeply aware of the history of art and culture, pointed out the absurdity of classical heroism in her contribution to the 2013 Carnegie International. Sometimes you have to take a break from posing and have a smoke. Standing on a pedestal all day must be tiring. Additionally, in the Beer Gardens, Eisenman draws on the style of French impressionists, her brush creating a swirling optical event.16 Despite her homage, she is no flâneur, and this is not Bal du moulin de la Galette. Free of the pretentious spirit exhibited by much of contemporary art, Eisenman plays with art historical truisms with a strange combination of reverence and frustration.

Nicole Eisenman, Prince of Swords, 2013

Plaster, wood, burlap, ceramic and crystal, 77 x 46 x 27 in (195.6 x 116.8 x 68.6 cm)

Photo: Greenhouse Media

Courtesy the artist and Koenig & Clinton, New York

30. It is not clear, however, if queer formalism is "campy," though it does engage with the legacy of camp as Sillman astutely theorizes. We live in an age entirely run by irony, wonderfully gaudy performativity, and cultural naïveté—a veritable campy culture industry. Pop culture icons from Lana Del Rey to Lady Gaga have come to embody the neuroses of the Millennial generation, whose difficulty creating a culture of its own has left it permanently adrift in the Digital Age. Camp has become as entrenched within American culture as the capitalist regime itself, and may have thereby lost its subversive quality. In the spirit of 30 Rock, it is hip to be an outrageously uncool, yet somehow enviable, outsider. But Sillman is nevertheless spot-on. Camp retained its revolutionary sincerity in queer formalism when, all the while, camp became mainstream. Queer formalism is neo-camp and post-camp.

31. Queer formalism is not entirely theoretical, but it knows theory like the back of its hand. "Theory" is largely anti-feminist and anti-queer, but queer formalism must engage with theory in order to take it apart. Even Freud would love the grotesque, bitterly hilarious psychosexual vision in Eisenman’s Sunday Night Dinner.

Nicole Eisenman, Sunday Night Dinner, 2009

Oil on canvas, 42 x 51 in (106.7 x 129.5 cm)

Courtesy the artist and Koenig & Clinton, New York

32. Queer formalism can be represented both at the level of subject matter and at the moment of signification. It falls somewhere between representation and theory, sociopolitical effects and aesthetic origin. For example, Sillman’s Me and Ugly Mountain (2003) is perhaps a representation of the baggage of many years of "feminine hysteria" or "homosexual inversion," as well as the reflection of those biases in the visual arts. Still, queer formalism represents the opportunity to ease that history when it becomes a burdensome assumption about the "meaning" of an artwork. One must look beyond an initial interpretive assumption about content without rejecting what is "represented." Queer formalism is childishly truthful, but is nevertheless filled with lies, dreams, and possibilities.

33. Alongside its personal, embodied, human aspects, Me and Ugly Mountain also recalls the tumultuous erotics of paint itself. At once an abstraction and a landscape, the mountain is filled with orgiastic ideas, lines, and colors. It literally erupts on the face of the most essential mark—the horizon line—like a newly formed pimple. As a result, the mountain is not just a personal, psychoanalytic representation, but also a disruptive force buried within and essential to the material constructs of the scene.

Amy Sillman, Me and Ugly Mountain, 2003

Oil on canvas

60 x 72 inches

Collection of Jerome and Ellen Stern

Photo: John Berens

Nicole Eisenman, Conscious Mind of the Artist

(Subconscious Decision and Actions in Progress), 2007

Oil on canvas, 39 x 48 in (99.1 x 121.9 cm)

Courtesy the artist and Koenig & Clinton, New York

34. Above all, queer formalism is not limited to one artist, group, or medium. It represents the possibility of a new way to discuss art in a nuanced, inclusive fashion. Art history and criticism require reinvigoration, and Sillman, Eisenman, Adibi, and Churchman, among others, are at the vanguard of a necessary transformation that is decades in the making. All queer formalism requires is a willingness to listen and see and feel. Venturing into the unknown is a terrifying process; queer formalism asks us to embrace unfamiliar ways of relating to our bodies and those around us. It begs us to think critically about how we define ourselves. A willingness to begin that journey, however, can have exciting and unexpected results.

- Amy Sillman, Shade, 1997-98 Oil and gouache on wood 50 x 60 inches Courtesy of the artist and Sikkema Jenkins & Co. Photo: John Berens

Amy Sillman: one lump or two is on view at the Institute of Contemporary Arts, Boston until January 5, 2014. Nicole Eisenman: In Love with My Nemesis will run from January 24, 2014 to April 13, 2014 at the Contemporary Art Museum, St. Louis. Elise Adibi: Metabolic Paintings is on view at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study in Cambridge, MA until December 20, 2013. The author would like to thank Amy Sillman, Nicole Eisenman, Leidy Churchman, and Helen Molesworth for their overwhelming kindness. This article has especially benefitted from conversations with Elise Adibi, whose passionate dedication to the arts has been a source of inspiration.

[1] For a further discussion of Eisenman’s evolving relationship to lesbian identity politics, please see my essay "’Queered in Every Sense of the Word’: Sexual Multiplicity in Nicole Eisenman’s Beer Gardens", published in Tuesday Magazine, Spring 2012.

[2] Literary scholar Eric Savoy has used the term queer formalism to describe the work of Henry James and the nuanced relationship between sexuality and criticism. See, for example, Savoy, Eric. "The Jamesian Turn: A Primer on Queer Formalism." In Reed, Kimberly and Peter Beidler, eds. Approaches to Teaching Henry James’s Daisy Miller and The Turn of the Screw. New York: The Modern Language Association of America, 2005. "Queer formalism" has also been employed by Robert Sulcer to describe the ambivalent, shifting nature of the gay male critic in nineteenth century literature. See Sulcer, Robert. "Ten Percent: Poetry and Pathology." In Dellamora, Richard ed.Victorian Sexual Dissidence. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 1999. The usage of the term in the context of literary studies is certainly worthy of further consideration as it relates to the visual arts.

[3] The role of ownership with regard to gender and sexuality was brought to my attention by Ashley Temple and Stephanie Garland.

[4] Eisenman, Nicole and Brian Sholis. "Nicole Eisenman." Artforum (6 September 2008).

[5] Molesworth, Helen. Press preview for Amy Sillman: one lump or two. ICA/Boston, 1 October 2013.

[6] Conversation between Amy Sillman and Helen Molesworth, The Institute of Contemporary Arts, Boston. 21 November 2013.

[7] Lajer-Burcharth, Ewa. "The Inner Life of Painting." In Molesworth, Helen ed. Amy Sillman: one lump or two, exh. cat. New York: Prestel Publishing; Boston: Institute of Contemporary Arts, 2013. 85. See also Molesworth, Helen. "Amy Sillman: Look, Touch, Embrace." In Molesworth, Helen ed. Amy Sillman: one lump or two, exh. cat. New York: Prestel Publishing; Boston: Institute of Contemporary Arts, 2013. 51, 53.

[8] Richards, Judith Olch ed. Inside the Studio: Two Decades of Talks with Artists in New York. New York: Independent Curators International and Distributed Art Publishers, 2004. 247.

[9] Ibid, 91.

[10] Salamon, Gayle. Assuming a Body: Transgender and Rhetorics of Materiality. New York, NY: Columbia University Press, 2010. 140.

[11] Accessible via Google news archive.

[12] Nickas, Bob. Painting Abstraction: New Elements in Abstract Painting. London and New York: Phaidon, 2009. 224.

[13] Lajer-Burcharth, 85.

[14] Sillman, Amy. "AbEx and Disco Balls: In Defense of Abstract Expressionism." Artforum, Summer 2011.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Eisenman and Sholis.