Jessica Deane Rosner can’t discuss the inspiration for her latest exhibit. It might suffice to say that, last September, she experienced a terrible and life-changing event. It forced Rosner to reconsider her self-concept as someone bold and brave. The aftermath of this episode forms the subject matter of Manuscript:Word Drawings, in which Rosner spills the entire story, her “way of saying it without saying it.”

Jessica Rosner

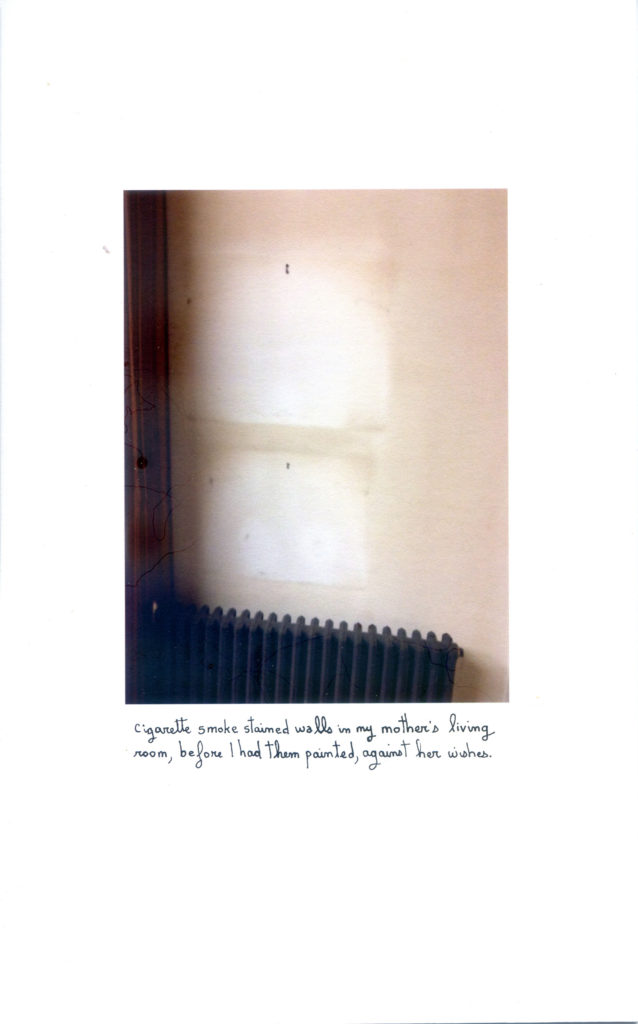

The Effects of Cigarette Smoke

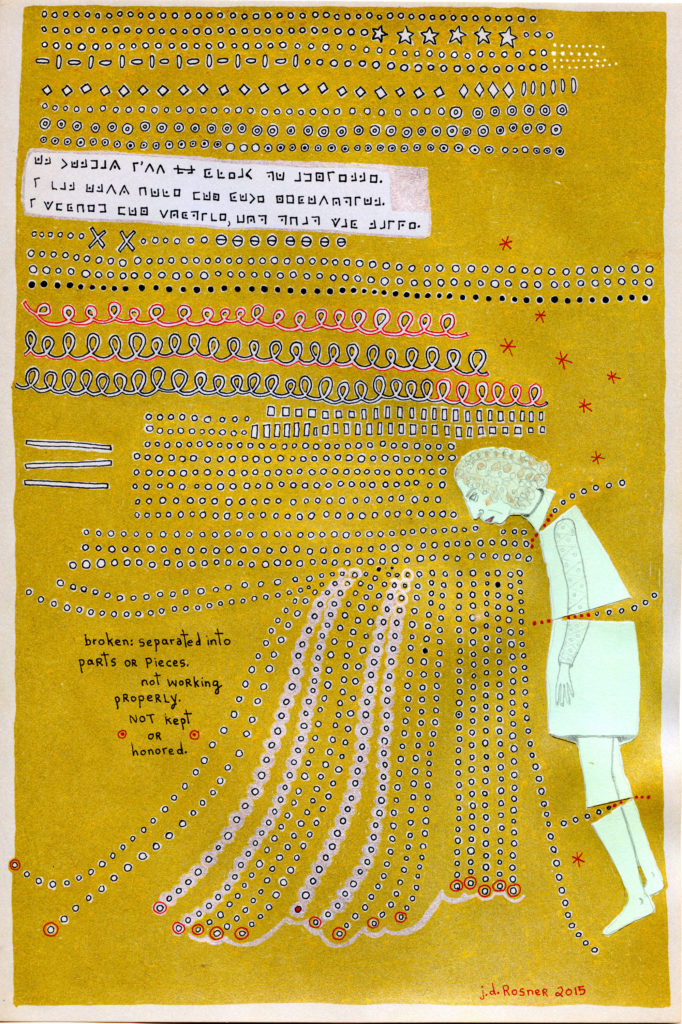

A substantive psychic injury is retold in a set of notepaper-sized drawings, each illustrated in Rosner’s thoughtful and unflinching style. The excruciating details shine brightly through clouds of golden ink. Distressed figures float amidst walls of indecipherable symbols (a coded retelling of the incident), whereas a severe vocabulary is more legible: Wound, Grief, Isolation, Betray. In the piece Manuscript: Acquiesce, Rosner crawls on the ground, her neck tied to a pole like an unruly pet.

Manuscript:Word Drawings is one half of the double-feature that comprises Rosner’s first solo show at Yellow Peril Gallery, with Stitching Mona occupying the remainder of the space. In creation and concept these bodies of work emerged separately, but there’s overlap in their emotion and epistemology (and the relation thereof). Both exhibits point to an inconclusive and more nuanced understanding of difficult feelings “Most people don’t spend a lot of time looking inward,” Rosner remarks. “They find it too scary, too painful and too embarrassing.” She is more willing to tackle the complexity of the unpleasant, even if the results might be unspeakable.

In Stitching Mona, for example, the work is inaccessible to the exhibit’s subject. Here, Rosner complements her previous parental panegyric: the epic Ulysses Gloves, which inscribed her deceased father’s favorite tome onto yellow kitchen gloves. Stitching draws its essence from her 86-year-old mother Mona Lenore Rosner, who suffers from dementia. On paper, Rosner reproduces Mona’s doodles with ink, gouache, and pencil, while vintage cloth provides a surface for threading words “lifted directly...from her rantings.”

Jessica Rosner

Label and Notebook gowns

Rosner’s most evocative use of embroidery comes in the form of fabric name tags she custom ordered. Over several years, Rosner meticulously sewed the labels into a gown worn by a 19-year-old Mona. Eventually, the white dress was covered with Mona’s maiden name repeated ad infinitum in tiny black text amidst a sea of pink rectangles. One might recall Tracey Emin’s infamous tent, another confessional told through stitches, which critic Kelly Grovier describes as containing the “private syllables of…sewn-on identities.” Emin exposes the “meanings…poised between what is secret and what is shared,” a feat Rosner also performs.

In 87 Flowers (Pretty Dangerous), each paper blossom—representing one year of Mona’s life— has been gifted a cigarette burn. These charred florals reference Mona’s penchant for chain-smoking, as does the pack of Marlboro Reds (her favorite brand) on a decoupaged table nearby. The tabletop arrangement—two books of Proust, the bogies and a photo of a younger Mona, hunched over in concentration—is elegantly punk, seemingly a good fit for Mona’s feisty personality. “Before she had dementia, my mom would say: Shit, fuck, piss and corruption,” reads one of Rosner’s embroideries, the cuss words threaded in an acerbic red. She revives her mother’s “unrealized” talents in the gallery space: “She is the artist. And I am the artist.” Yet an important question remains: does Mona approve?

“She can’t see it,” Rosner says. “And even if I told her, she would forget…My husband thinks she would be touched. I think she’d be pissed off.” She motions to the notebooks and novels, the appropriated words. “Especially this stuff. She was never a sentimental person.”

A comparable presentation of filial grief is Sophie Calle’s Rachel, Monique (2014), an installation-cum-eulogy for her mom Monique Sindler, who died in 2006. Like Mona, Sindler favored Proust and smokes. Calle’s effort, as in Rosner duplicating her mother’s notebook musings, resuscitates the maternal text; the French artist enlisted actor Kim Cattrall to record revealing excerpts from Sindler’s diaries. While these projects share in the public display of mourning, Calle’s posthumous memorial imparts a certain sense of finality that Rosner’s lacks. Mona is alive, but Rosner explains she is no longer the same person as the dementia worsens.

The waning of capability seen in old age is often absent in North American discourse about the elderly. In a 2014 article, anthropologist Sarah Lamb suggests widening our acceptance of aging’s inalienable pitfalls, “to come to better terms with the normal human conditions of decline, dependence, and death.” She calls for “a recognition of meaningful decline as a valid dimension of aging and personhood,” which “the prevailing successful aging model, in popular discourse, biomedicine, and academia, does not include.”

Stitching Mona discards the standards Lamb describes and instead accommodates uncomfortable truth. Rosner feels her goodbyes have already been said. In the gallery, one confronts Mona’s absence, receiving it not as Rosner might but as something nebulous, uneasy and bittersweet. The knowledge that Mona can’t see the exhibit (worse yet, that she might not like it even if she could) precludes any sentimental solutions. Similarly, the Manuscript drawings might initially draw our curiosity through narrative—until we scrutinize the drawings closely, and realize the despondency they were intended to dispel.

Given current political and social happenings, Rosner claims her troubles are “not even in the same orbit.” Yet she remains somewhat vexed by last year’s dilemma: “Why did this thing bring me down? Because I am a strong person…I don’t know the answer to that. I think part of it is not being able to talk about it.” These exhibits incant sadness to give it form. No, materializing the trauma will not kill it, but it does render visible the fallout.

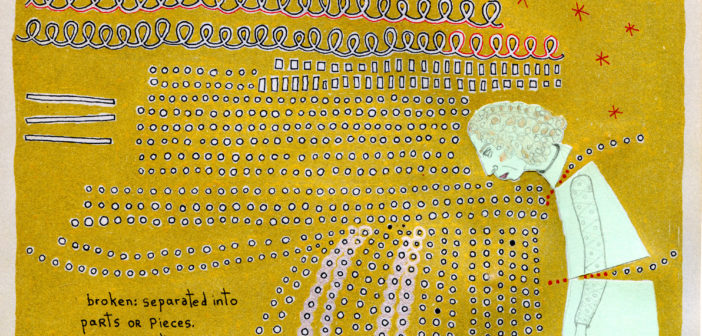

Jessica Rosner

Manuscript: Broken

Rosner admits the Manuscript drawings were “hugely cathartic” as she navigated her confusion. They became a means to transcribe, slowly and with care, the unpredictability of despair. Rather than inviting pity or sympathy, this record instead asks that we might recognize our own unresolved shit, to borrow one of Mona’s favorite words.

“I really don’t believe in life there is any closure,” Rosner says. “If you get closure, it’s a miracle. You just have to accept the fact that there will always be mysteries and unsaid things.”

In a nation beset with prescriptive happiness, however, the mere acknowledgment of lasting, stubborn or complicated sorrow might become radical. Anguish is often displaced or sacrificed to empower illusions about personal strength. Pain’s tutelage can be destructive, not enlightening, and time is an unreliable healer at best. In Rosner’s work, there is no naiveté about the alleged medicine that is hardship. Instead, there is vulnerability, a rarity in a culture that encourages invincibility at the expense of humanness.

- Jessica Rosner Mona Doodle

- Jessica Rosner Manuscript: Secret