“I make these when I’m not making my ‘real’ work.” I heard this statement fall out of my mouth and stopped myself, horrified. I was at the opening of the BLAA Summer 2016 exhibit You Think It’s ____, But It’s Really ___, nervously explaining my piece to a fellow artist. In one sentence, I was both illustrating and undermining everything I wanted to talk about in my piece. My internalized ableism was rearing its head. I was showing a piece comprised of 84 collages made over the previous 6 months, shown as a slideshow. These collages were made on my iPhone and include photos of drawings, stills from private performances documented on my phone, selfies, and snapchats, all run through various free apps. The images are chopped, layered and repeated to create the collages. This method of working let me access my catalogue of visual references at the swipe of a finger. From under the covers of my bed, this process allowed me to develop my work outside of a traditional studio setting.

Rosie Ranauro, 2016. "It's not meant to be strife #2." Digital media.

For a long time, I didn't consider these 'real' works. Real work happens on canvas. Real work takes up physical space. Real work requires physical labor; otherwise, how would you know it was ‘work’? When I look back at myself making paintings in college, I remember struggling to stretch canvases. The action made my hands burn and go weak for hours and my knees and hips lock from the concrete floors. Professors would caution against cutting corners in the studio, but I would default to ‘lazy’ choices in pre-stretched canvases and watch my panels warp because I hadn’t prepared them properly. I would think to myself that “I could be a good painter if I wasn’t so lazy.” I always felt like my ideas were ahead of my technical competency. I cited laziness for the shortcuts I would take, the same laziness that makes my car so messy and my dishes sit in the sink. This idea of ‘laziness’ seeped into my identity. Years later I looked back and recognized these shortcuts were not laziness but attempts to conserve energy before I was aware of why I needed to do so before I had a name for what I was experiencing. My comment about my collages not being my “real” work was a reminder that I’ve not completely unlearned these ideas, even though I no longer believe them.

The topic of “realness” is a quick way to discredit others in their contributions and accomplishments: getting a real job, being a real adult, to name just two of the many ways I’ve heard that phrase used outside of an art context. I’ve heard countless artists tell me that they were not a ‘real’ artist because they lacked a degree or were working non-art jobs out of necessity. This concept of ‘realness’ in my case is applied to maintain the relationship between goodness with labor and laziness (or badness) with ‘disability’. The conversation needs instead to be about what we are calling ‘realness’ and its relationship to privilege, in every sense of the word. Who better than artists to not only open up a discussion about this but to hold ourselves accountable for where we are perpetuating this in our community. We need to look closely at what we value and what we don’t when determining creative worth. I think we place a lot of value on physical bravado—big paintings, body-testing durational performances, exhibits of extreme physical labor. We need to broaden how we define in contemporary art to make space for all kind of makers. We need to make space for artists who are physically (or otherwise) limited by asking ourselves why we value certain types of work over others. Accessibility in the arts is about so much more than becoming ADA compliant; we have to make the dialogue accessible to everyone from the start so that we can build a community that serves everyone, where everyone’s voices can be heard, not just a privileged few.

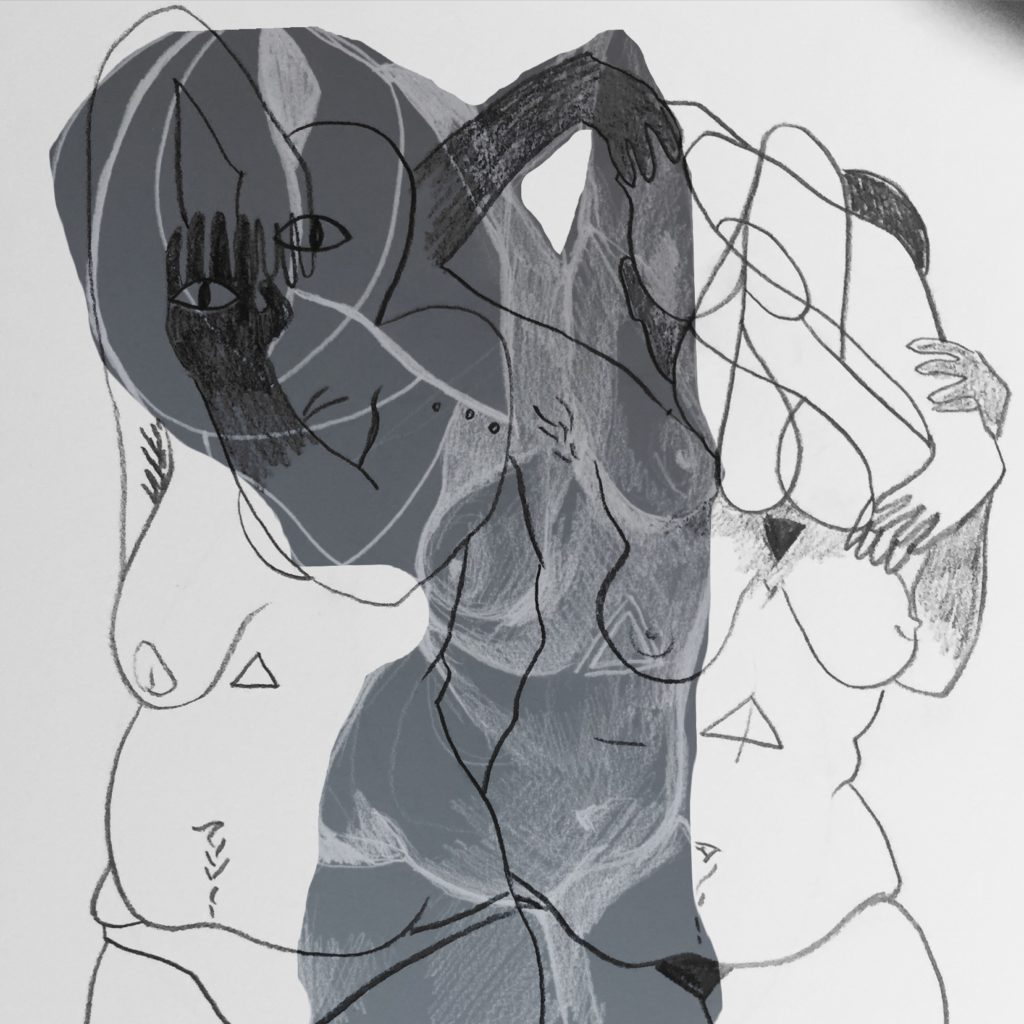

Rosie Ranauro, 2016. "You're so brave." Digital media.

Any person with chronic fatigue can tell you that, for them, a bed is more than just a place to sleep at night. The bed represents healing, as well as isolation. Depression can find you under the covers. Making art from my bed has been a major form of resistance for me: there is some comfort in feeling like your mind can keep active when your body needs rest. I can stay curled under the covers, holding my phone close with the warmth of my partner next to me. Without any physical exertion, I have access to an entire catalogue of images in my iPhone library. Many of my source images are created from my bed, by documenting 1-3 minute performances or creating selfies. Periods of illness medicalize my body and I become a set of words on a chart that I try to put out of my mind. Medications make me cloudy, make me put on weight. I look down and don’t recognize the shape of my stomach, my face looks tired and I don’t feel like I am my own. Chronic illness makes me feel out of control of my body but making my work brings me back in. The images I make can be are printed directly from my phone to my printer, where I can print multiples and manipulate, creating layers with vellum, isolating and accentuating with ink and graphite or I can work with them directly on my phone, layering in other imagery I’ve been collecting. In this work, I can respond to my figure as objectively or as emotionally as I need to, and I am able to achieve focus and flow when the physicality of my studio feels inaccessible.

Rosie Ranauro, 2016. "It's not meant to be strife #1." Digital media.

I’ve started posting this work on Instagram over the last year, almost as fast as I’ve been making it. I’m sure there are people who look at that and equate my quickness to share with selfie culture (not to mention the easy target I become as a woman making work about her body), but my quickness to engage online is more than a need for likes and validation. The importance of access to a community via the internet cannot be underestimated for anyone who is chronically ill, never mind a sick artist, for the way it provides social access even when they are not physically able to make it to events or gatherings. The internet gives my work and my body visibility when I’m feeling isolated in my illness.

Allowing myself to redefine how I think about my creative process has allowed me to keep making work through the hardest time in my life. By not limiting myself or categorizing work created outside of traditional studio methods as ‘not real’, I am freeing myself up as a creative person to make work unbound by traditional limitations. I don’t need to legitimize my work by working in specific mediums or showing that I was capable of the physical rigor we so often associate with authenticity. There are many paths to creating your work. It is all real work.

- Rosie Ranauro, 2016. “Many Selves.” Digital media.

- Rosie Ranauro, 2016. “lifelong.” Digital media.

- Rosie Ranauro, 2016. “//////o\\\\\\”. Digital media.

- Rosie Ranauro, 2016. “You’re so brave.” Digital media.

- Rosie Ranauro, 2016. “Why did u separate me.” Digital media.

- Rosie Ranauro, 2016. “It’s not meant to be strife #1.” Digital media.

- Rosie Ranauro, 2016. “It’s not meant to be strife #2.” Digital media.

- Rosie Ranauro, 2016. “Try not to hurt yourself.” Digital media.

- Rosie Ranauro, 2016. “Looming.” Digital media.