Jamaica Plain-based painter Josh Jefferson has recently received a lot of attention for his brightly colored geometric collages and head series. Jefferson will be showing his work at Steven Zevitas in the SoWa district on September 9 and has shows lined up in NYC, LA, and Milan this upcoming year. I first discovered his work through Instagram and was immediately drawn to the beautiful and subtle color palette of earlier collages. His newer work is punchier and more dynamic. He has an excellent grasp of form and his color choice is sophisticated in its directness (interestingly enough, later I learned he is color blind). I was excited to learn that he is based in Boston, I reached out to do an interview. Jefferson invited me to do a studio visit of his newest work- large-scale abstract paintings made with a homemade 12” paint brush and layers of vinyl paint mixed directly on the canvas. We talked about the playful interaction Jefferson and his son have through making art, the concept of a painter’s “language”, and his process.

-------

Farrell Mason- Brown: Has fatherhood changed your relationship to art?

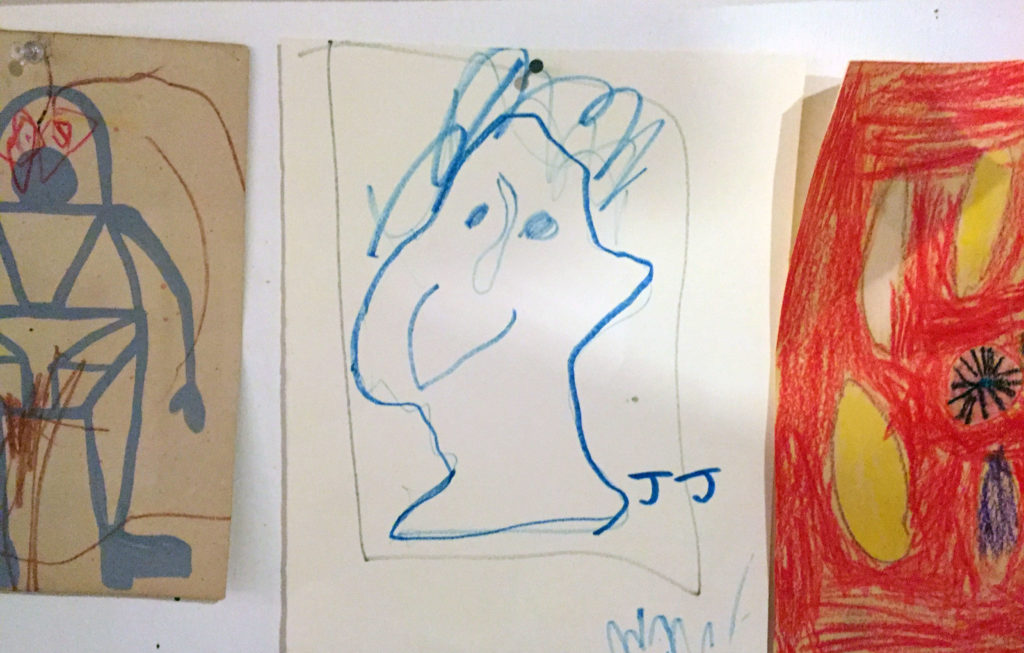

Josh Jefferson: I would say 100% I didn’t start painting till my son Hunter was born. What happened was that I had less time, and with that pressure, I had to make a choice, and it was either I could go to sleep, watch TV, or get to work. I only have 2-3 hours a day. I became more disciplined and focused. And also it’s the creative process of being a father and growing with him, and making art with him. I still use his art in my collages. And he imitates my paintings. We have a nice back and forth through art.

FMB: I love kids’ art. They use space in such a refreshing way.

JJ: Yeah, it’s immediate; there’s no filter. It just comes right out.

Homemade 12" brushes used by Jefferson in his studio

FMB: It’s interesting that you schedule and structure this 2-3 hours to paint every day but in that structured time you aim to be unstructured and open to inspiration.

JJ: Laurence Stephen Lowry said inspiration is hogwash. It’s really just about consistency, or rather, working every day. Being persistent is the only way you can grow. You have to be constant and hit these points over and over again. And luckily if you can, you’ll get to some unknown, a new growing point. And you just do it over and over.

FMB: By hitting points do you mean themes you want to work on?

JJ: Through process you find certain things that have worked and you keep adding them to your vocabulary. Like in music you learn how to make a chord and then add that chord to the melody. The more you hit certain points the more you can enlarge your language.

FMB: Can you explain what you mean by language?

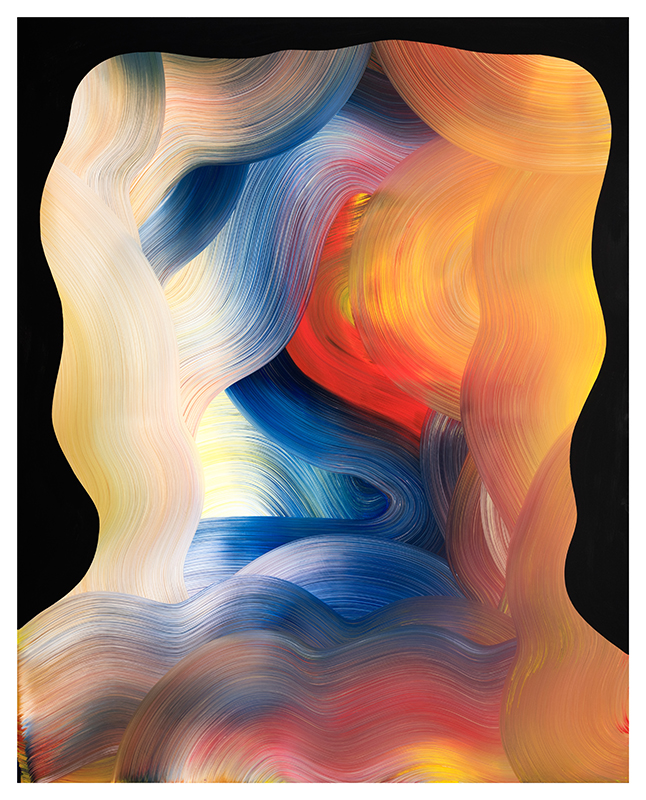

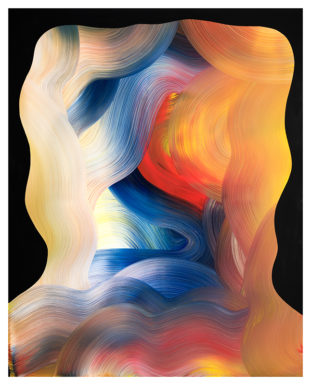

Josh Jefferson, Is that you Pumpkin, 2016, Acrylic and flashe on canvas

JJ: I really think that language is the hallmark of a good artist. If an artist has a language that’s big enough and strong enough to build their world up inside it you can see it. Take Philip Guston; he is really great and completely developed his own language, not just some words that were his own. He went through a breakdown where he could only draw a line. When I started making art again I went through a similar shakedown. Collages didn’t have enough “hand”. I took a year and just drew; eventually, I cut up the drawings and collaged them to flush out the concept. Like anything worthwhile you have to work at it all the time to start developing your language.

FMB: What about the trend of making a brand in art, like artists that make art that is always violent or grotesque, would you say that’s a limited language?

JJ: Not limited but I do think what matters is when the language is really worked out and developed. I think that’s deeper and truer than when somebody riffs on the same thing that works and doesn’t grow from it.

FMB: Besides painting, how do you to enrich and build your language as a painter?

JJ: Talking; I think artists should talk to each other. I realized that over this weekend. I got to do a studio visit with Austin Lee. It’s reassuring because we’re all in this great unknown, in this subjective area. It’s nice to have a community. And that’s where the gallery comes in.

If it works right, galleries create a relationship and build a community. We need each other—it’s symbiotic. Also, Instagram is a great new platform for interacting with art. I see a lot of art through Instagram by following artists and galleries. And it’s nice because now you don’t have to live in New York to be that engaged like you did 20 years ago.

FMB: To me, your paintings have a lot of freedom and beauty in the brush strokes, yet are often contained by heavy outlines. How do freedom and control play off one another in your paintings?

JJ: Working with a big brush and painting with my whole body is the freeing part. I mix the paint directly on the canvas with full body movements. I don’t think; I just go for it. And then I cut the shape in with the black paint- that’s the control part. When I cut in, it’s more deliberate. I’m choosing to make it look like a certain way.

Josh Jefferson, Untitled, 2016, Acrylic and flashe on canvas

FMB: How do you manage that balance?

JJ: Well there’s a certain amount of control needed. Then, if things don’t turn out the way you intended, you go with it, you adapt and that’s the control of letting go. There’s a book called Flow by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, it sounds really cheesy but it’s great. It’s a study on people who are highly skilled and work on one specific thing for years, like professional athletes and surgeons. When you’re in the zone you’re not thinking—that’s freedom. But you only get the freedom if you have mastered the control part. You have to be really skilled to get that free.

That’s what I do for the big paintings, sometimes I’ll try to think and say maybe I’ll put a curved yellow here and then I’m like fuck that. I put the paint on the canvas and just step up and do it. And then look back and say oh it’s awful (laughs).

FMB: You were a free jazz musician for around 20 years, playing for small audiences—what did you learn from that time in your life?

JJ: We made music that’s not for the faint of heart (laughs); it was completely improvisational. We made a type of music that was kind of like collage and you could draw a parallel between that style and the paper collages I went on to do. I didn’t turn away from music but painting pulled me back in. It’s something about the investment in time; I get more back in return from painting. I love music because it’s bigger than you; you play with 3 or 4 people. There’s a certain mental looseness that I learned from playing music- I look at something and wonder if it could be cut away and I do that with my art too.

The way I played was simple. The simpler the better: brevity. That’s what I aim for with my art too. Directness has a velocity to it; there are no fads. There’s a truth to it. To me, it feels like the best thing I can possibly do.

FMB: Heads appear over and over again in your work—what’s the significance of this image?

JJ: Betty Blayton talks about how she paints on these circular canvases over and over. She does the same thing again and again, she twists and pulls and the circles help her grow as an artist.

The head is helping me grow—they’re always changing. When they work really well they can dance along the line of abstraction itself.

FMB: There’s a lot of importance put on conceptual and theoretical art. Do concepts and meaning emerge for you in the process of creating this series?

Josh Jefferson, Gummy Bear, 2016, Acrylic and flashe on canvas

JJ: That stuff is such a drag and such bullshit. Maybe concepts emerge for me as an afterthought but that’s not what the definition of conceptual art is. I was reading this Christie’s catalog and this artist Joe Bradley had an artist statement that read “I don’t like reading other artist’s statements so I’m not going to have one here” or something like that and his titles were “Working on a Title”. That’s brilliant!

It’s hard to talk about anything deep without sounding like a pompous douchebag. People are either ironic or overly real and then you don’t even want to listen to their story.

What works for me is that I’ve been creating bodies of work. I’m not the kind of painter that connects emotional things. If I’m angry I don’t paint an angry face. I don’t work that way. I focus more on my process, which is intuitive.

Ideally, for me, when I’m painting I’m not thinking at all. Forms emerge, and words emerge, but they come from somewhere else. Art is all about the gut, not the brain. It’s how you feel, how you respond that matters. In other words, there are no words.

-------

Versed in consistency and improvisation, and mastering his own process, it makes sense that Jefferson has been so prolific and successful in the past couple years. It was impressive to meet someone so energized and immersed in art, and getting recognized for it. With his fame rising, his style rapidly developing, and his exhibition schedule accelerating, it felt like he was on the brink of something big. Riding forward in a subjective unknown territory, but staying above water. Only because Jefferson is so well equipped with the necessary skill and language can he so calmly and adeptly ride this mounting wave.

Josh Jefferson's solo show, Shaboopie, will be on view at Steven Zevitas Gallery from September 2 to October 29, 2016. To visit the gallery's website, click here.

- Josh Jefferson, Gummy Bear, 2016, Acrylic and flashe on canvas

- Josh Jefferson, Is that you Pumpkin, 2016, Acrylic and flashe on canvas

- Homemade 12″ brushes used by Jefferson in his studio

- Josh Jefferson, Untitled, 2016, Acrylic and flashe on canvas

- Josh Jefferson in his studio, 2016

- Untitled, drawn by Josh’s son imitating Josh’s style and signature, 2015, Crayon