“The best art speaks for itself,” someone stated at a recent public discussion about Boston Creates. My immediate internal response was yes, but art also prompts, at times even goads, us to speak or write. I concede that art is, of course, first about one’s sensorial experience of it, and there is much to be gained from this act alone. There is also much to gain from speaking, reading and writing about art as an intellectual and social–even civic–activity. In fact, these activities are vital for an active and dynamic arts ecosystem that becomes through a system that supports not only art making and exhibition but also discussion. These are not new ideas, just ones that often seem to be sidelined and taken for granted as part of an undercurrent of work by educators, curators, and arts writers.

Greater Boston’s arts ecosystem is the focus of Boston Creates—a plan which outlines goals, strategies and tactics that among other things advocates for an increase in access, communication across the City’s siloed communities, risk-taking and a diversification of platforms for the arts to thrive and for people to find personal value in creative experiences. Both art writing and art-making demand risk that we can only hope will be met by an environment of respect and informed honesty.

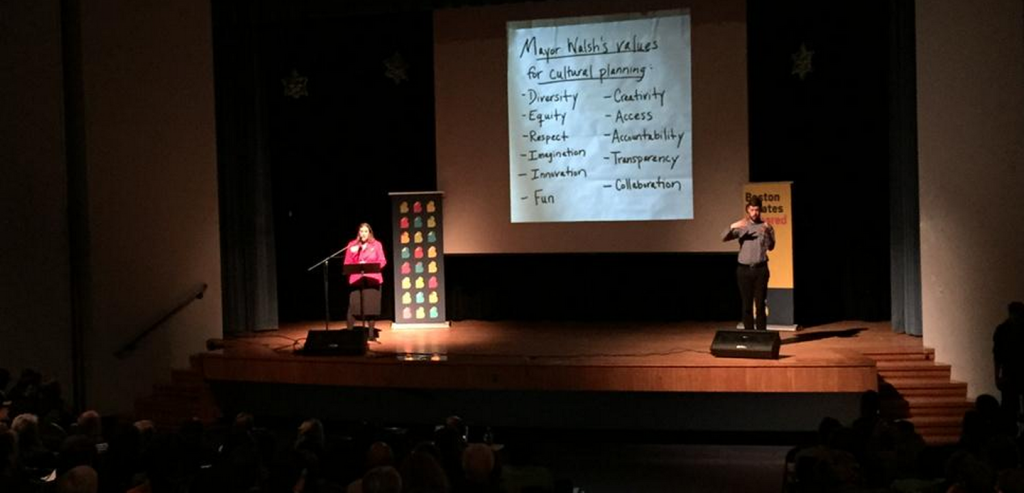

Boston Creates Town Hall Meeting, June 2, 2015.

Courtesy @MidwayArtStudio

In Boston, we are fortunate to have platforms—blogs, online and print publications, and radio programs—that focus on the arts. Some of these materials can be categorized as promotional material (press releases or surface reviews), others as arts advocacy or behind-the-scenes coverage, and still others as important forums for broad and varied reflections on art. All of these are important, but I elect here to focus specifically on art criticism—not to be confused with snarky or negative commentary—and to state plainly that we could use more of it. Art criticism, as proposed here, is writing that offers a sophisticated assessment of art and the experience of it, placing the work within a frame of reference that is informative and thoughtful. Art criticism is valuable in that it provides regular readers with language and background information to be repurposed as tools to articulate readers/viewers’ judgments of art. But where does art criticism or public forums about the arts fit into the arts ecosystem in Greater Boston? What role does it play and what are the City’s particular challenges and needs in regards to such platforms?

These questions are not novel or even new to Big Red & Shiny. In 2012, former BR&S editor and founding contributor, Christian Holland published the short essay “Why We Write,” quoting the Boston Globe’s Cate McQuaid’s valuation of art criticism as an important part of the arts ecosystem. The essay also expounds on the then-limitations of the mostly commercial coverage of McQuaid and the museum-only coverage of the Globe’s Sebastian Smee. In 2013, BR&S Managing Editor Brian Christopher Glaser shared curator Renny Pritikin’s “Prescription for a Healthy Art Scene.” On Pritikin’s list of recommendations is “sophisticated, open-minded art writers and journalists to document, discuss, and promote new art ideas,” and publications that support their work. The same year, Jason Turgeon shared a crowd-sourced map of Greater Boston’s arts ecosystem—a work in progress and need of updates, but also worth a look.

A view of SOWA First Fridays from 2008.

Photo courtesy of James Manning.

The frustrations of 2012 were exacerbated earlier this summer when the Boston Globe announced changes to its art reporting that would reduce coverage of small exhibitions and gallery shows. The news led to an eruption of unhappy responses that Globe staff members sought to allay by assuring the public that art coverage will continue. Great, but coverage of what? What venues and artworks deserving of attention will be ignored–not just on occasion, but continuously? And how does this impact the environment in which artists in the area are working? Reactions to the Globe’s changes clearly showed the desire for more diverse coverage of shows; art and exhibitions are clearly made to be seen, and the critical documentation of a broader range of shows can build momentum and collaboration in a city of Boston’s size. The limitations of art criticism, though, are tied to its murky, continuously evolving role, which, is further complicated by the limited funding available for arts publications—including digital ones—for arts writers, and, of course, for artists in general. Furthermore, the Boston area’s universities and large cultural institutions do much to fuel the conversation about the arts in general, but these discussions are too often insular and not broadly advertised. And while these discussions touch on all aspects of art, they don't produce or circulate art criticism, per se. Frankly, it’s not their job, and it is beneficial to have arts writers that move through these circles but are stationed outside of them. Thus universities do not fill the gaps in coverage of the arts being created and shown across the city.

Summer Summits, July - August 2015, Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts.

Let’s think back a bit, to consider moving forward. The rise and solidification of art criticism in the eighteenth century and its popular dissemination historically was a symbol of the democratization of the field, a shifting of power away from the monarchy and the allowance of new critical voices to emerge and debate the higher purpose of art and issues of talent and taste. As the field has expanded and diversified in pace with art making since the 1960s, there has been much debate about best practices, the goals, and value to various stakeholders (artists, collectors, arts professionals, academics, and viewing publics). There has also been debate about the stakeholders: which critics or publications serve whom? The critic traditionally has been a practiced commentator on art; in the best instances, a person who offers digestible and insightful treatises that respond to and collectively shape the circulation and reception of art. But as technology and the market have changed, the platforms available for forums on art have dramatically transformed as well, marking a seeming rise in coverage that has coincided with dwindling support of art writing and a questioning of the quality of the content and the form this commentary should take. James Elkins's What Happened to Art Criticism? (2003) is still a shadow looming over the field.

More interesting for this discussion, however, are the responses to this “crisis” a decade later. Marek Bartelik (former President of AICA International, art critic-historian-poet) rightly points out in "'Is There a Crisis in Art Criticism?'" that these days “the informed insider has been largely replaced by a fast-moving, semi-professional, often freelance, critic-curator-art agent (sometimes also an artist), who pursues a career that might or might not last longer than a few years…” How does this impact art writing? Anecdotally, it increases the voices, while decreasing the time available to develop a voice. Simultaneously, while wearing many hats (albeit of the same color or brand) may enhance one’s toolkit, it can also create poor (in the financial sense), sleep-deprived, and schizophrenic arts professionals who are looking at a lot and seeing very little. It increases content, but the scope is often limited. The system does not support sustainability and often encourages hyperactive attention to the pageantry of the rotating roll call of who’s who.

Reactions to the spectacle that we all have witnessed and that Bartelik overtly states also has led to a multitude of publications with unique agendas, foci, and publics—some smaller and more focused than others. The global “crisis” of the fragmentary field of criticism (fragmentary by nature as criticism’s audience is obviously more engaged with the writing that connects directly to the people and institutions with which the audience engages) continues to be de-centered as regional-focused platforms emerge. In continuing to problematize the “crisis” of criticism and to advocate its continued significance, let’s consider the challenges the market has presented to artists as well. As Bartelik's pithy remark makes plain in the aforementioned text: “While the global population of artists increases, their conditions often worsen. Artists, like the rest of the population, might be divided between the 1 percent and the 99 percent.” To a degree, Boston Creates is trying to address this problem in a meaningful way. But its tactics have yet to include criticism as a necessary part of an arts ecosystem (at least to my knowledge). If no one experiences, documents, or critically responds to the work being produced, what’s the point?

In researching broadly, and continuing to think specifically about what art criticism means to Bostonians, I found several treasures relevant to prevailing discussions around art and its criticism in our city. I’m choosing to share reflections on “The Role of the Art Critic,” as it provides perspective on how this contested role continues to change with art and the rest of life.

“The Role of the Art Critic,” published in Canadian Art in 2014 by Toronto-based critic Alison Cooley, includes a selection of 10 questions from a survey that the journal originally published in 1966. The questions touch on the basics: Is art criticism necessary? Who is its audience? How can one qualify good criticism–what is its content and tone? What is its ultimate purpose? Cooley printed not only a selection of these questions in the 2014 publication but also contemporary responses from arts administrators, curators, editors, critics, and artists. The feedback on the craft and consumption of criticism range from the artist who admits only reading reviews of his work to a critic and curator who states that criticism should share “a singular experience,” while “grounding (context, history, etc.) and transporting.” Another critic-curator admits, “I still don’t know who I am writing for…” And then there are reflections on the distinction between publicity and criticism itself. All of these questions seem a good check for anyone engaged in the art field, and worthy of discussion for the few platforms in the area that offer arts criticism regularly. It seems inevitable (and advantageous) that the answers would vary.

As James McAnally and Sarrita Hunn, co-founders of Temporary Art Review, assert they decided to respond to work that is likely not appealing to the “mainstream audience, but that cultivates a public conversation around work [they]find valuable: There is value even when “Criticism…performs more like a condensed conversation in a small room, which still has power, but not an expansive audience.” This perspective could be applied to many scenarios and settings in the region, and the sharing of texts across these small rooms could form a house that could ultimately be more inclusionary than the limited number of publications now allows. In other words, I am not advocating elitism or exclusivity, but arguing that we need a system that supports enough strong-voiced, thoughtful critics to cover an expansive selection of the arts being produced and shown in the city. I too champion the accessibility of visual arts but also believe strongly that risks are worth talking about even when they “flop,” even when executed in a scrappy venue, even when there may only be a small audience who cares. This is where judgment should kick in, and when we should hope for critics with distinct interests and voices. Sometimes beneath the polish or in an unexpected venue, we find something that excites us and encourages us to look more deeply… to ponder… and then, perhaps even to speak, to write, to read, and to look again.

So what do Bostonians have to gain by providing and cultivating critical dialogue on art-making in our City, and perhaps even the surrounding region? The Creative Plan asserts that “Together, we can build/shape/define Boston’s creative future.” But how can we do this without critical words that respond to the art produced? What role does art criticism play in supporting the arts in the City? It is and will be part of the infrastructure, but how should it be supported? How might it address participation barriers and support the off-centered work being done in the City?