As part of their Northeast Exposure Series, the Photographic Resource Center at Boston University presents Honky Tonk: Portraits of Country Music 1972-1981. The exhibition features the work of Henry Hornstein, a New Bedford native, currently a professor of photography instructor at the Rhode Island School of Design. Based on his recent Chronicle Books publication of the same title, this collection of photographs documents the culture surrounding country music - its venues, its patrons, and its musicians. Depicting different locales of the country music scene that range from the famed honky tonk, Tootsie's Orchid Lounge, to the former home of the Grand Ole Opry, the Ryman Auditorium, just "39 steps" away. This show, however, focuses on country music's ties to the New England area. "A lot of people assume that country music is a southern thing. It isn't: it's everywhere," Hornstein says. Backing up his statement are his backstage shots of a smoking and strumming Waylon Jennings at the Performance Center in Cambridge, Don Stover and his banjo at home in Billerica, Tex Ritter at the Hillbilly Ranch in Boston, and Dolly Parton at Symphony Hall.

Beginning as a history major at the University of Chicago in the 1960's, Hornstein became interested in photography. When he saw the work of Robert Frank and Danny Lyon, he decided to make the "uncertain transition from academic to artist." After coming back to New England, he took a class with Minor White and taught at Project Inc. in Cambridge before heading to RISD to study with Harry Callahan. His uncertainty led him to an outlet for his earlier interest in history through his new vocation by "photograph(ing) people and places to which I was naturally drawn," Hornstein recalls. A lifelong fan of country music, he brought his camera into the bars and concert halls and began to make pictures at the shows he frequently attended.

Hornstein's background in history is an interesting footnote. He saw the country music culture as "(a) disappearing world that I wanted to preserve on film." Anticipating this loss, he began to see it as his responsibility to document, fulfilling his wish to, "take pictures, make books, and record history." When researching in his pre-photo days, his visual source material would have been monochrome photographs and reproductions. As color photography became more available, it became the look of the contemporary. Hornstein admits as much when he comments on his use of black and white photography. His explanations range from defense ("I just like the way black and white photographs look; they seem more timeless") to valorization ("Also, they are more permanent - less likely to fade with time - and this fits with my general goal of using the camera to record history"). The look of history is black and white and Hornstein capitalizes on it. The subjects of the images are further distanced by the medium, heightening both the sense of loss and the audience's desire to remember.

This is where the objective view of history breaks down, and where its subjective nature appears. Recognizing that "much of the folk and country music tradition is narrative, describing stories and events often historical or legendary in nature," Hornstein has developed a transparent, bare-bones method of working that is analogous to how country musicians feel they perform their songs: "with directness and honesty". The photographs have the look of what country music sounds like. Honesty, though, in either case, is not a virtue. It is an affect whose style is seen as a virtue. The photographs are dramatic even though formal elements in the images are not - they push events away from what one would recognize as history and place them into mythology.

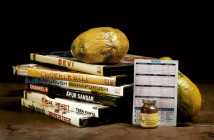

Included among his framed gelatin silver enlargements is a display of ephemera related to Hornstein's career. In a case near the back of the gallery is a spread with descriptive labels whose contents include: various Rounder Records LP jackets he had shot as during his professional association with the company; t-shirts emblazoned with two-value reproductions of country artists that were sold at venues like Tootsie's Orchid Lounge; a custom made "HENRY" sweater made by the "Lone Star Lady" at the Lone Star Ranch in New Hampshire; a first edition copy of Black and White Photography: A Basic Manual, his original manual on photographic technique. This presentation pitches Hornstein into an arena where he is a historical figure whose work is now a finished body worthy of study. Hornstein himself is now at a point in his career where he is as much of a subject for archiving as the culture he once photographed. He becomes a fascination just like those he has represented in his photographs. This means that the biography involved in making this set of photographs is now the part of this show's attraction.

The most fascinating object in the case is the first record that Hornstein ever purchased–Johnny Cash Sings Hank Williams. This album is one renowned (now legendary) musician paying homage to another beloved (also legendary) country musician through a reverent interpretation of the songs. This album not only a way for Johnny Cash to pay respect to another musician whom he admired, but it also concretized Cash's credentials as a country music heir. This record that Hornstein bought as a kid in Massachusetts can be seen as defining the character of the photographs he was to make later: a reverent representation of others within the community in which he was involved.

- Henry Horenstein, Waylon Jennings, Performance Center, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1974, Gelatin Silver Print

- Henry Horenstein, Harmonica Player, Merchant’s Cafe, Nashville, Tennessee,1974, Gelatin Silver Print.

- Henry Horenstein, Waiting Backstage, Grand Ole Opry, Nashville, Tennessee, 1972, Gelatin Silver Print.

----

Links:

Honky Tonk Book

Photographic Resource Center

"“Honky Tonk: Portraits of Country Music 1972-1981” An Exhibition of Photographs by Henry Hornstein " is on view March 25 - April 25, 2004 at Photographic Resource Center at Boston University.

All images are courtesy of the artist and the Photographic Resource Center. © Henry Horenstein/ Robert Klein Gallery

Matthew Gamber is a regular contributor to Big, Red & Shiny.