In Marguerite Yourcenar’s essay, “That Mighty Sculptor, Time,” she speaks of the “involuntary beauty” of ruined sculpture from the ancient past:

…statues so thoroughly shattered that out of the debris a new work of art is born: a naked foot unforgettably resting on a stone: a candid hand; a bent knee which contains all the speed of the foot race; a torso which has no face to prevent us from loving it; a breast or genitals in which we recognize more fully than ever the form of a fruit or a flower; a profile in which beauty survives with a complete absence of human or divine anecdote; a bust with eroded features, halfway between a portrait and a death’s head.

Yourcenar’s words resonate with Providence-based artist Dennis Congdon’s recent paintings, which he refers to as “Congeries” in his magisterial solo show (2015) at Zieher Smith and Horton in New York.[i]

The mature Congdon’s painterly preoccupations are apparent in enchanting images, congeries of ruins and regrets. Each of these large paintings is an excavation site of sorts, archaeological and psychoanalytic, where the art-historical archive bubbles up from the realm of the unconscious through the painter’s eyes. This “deposit” of an individual artist’s relationship with the deep history of art is configured warmly and with abundant light; the relationship is profound, but not heavy or confining. The lyrical and beautifully painted object-fragments embedded in landscapes of rarified color exist at various levels of sentience themselves, inviting affect and attachment on the part of the beholder.

Dennis Congdon, Caryatid, 2015.

This body of work, which Congdon has been developing since around 2000, deals with the transience and mortality of images relegated to the painted unconscious of a cultural present and past. Congdon’s forms are mediated by stenciled shapes that are transferred to the canvas with all of the abandon and precision of masterly freehand drawing. The painter states that these reproducible stencil markings are like the sinopia drawings that undergird Italian Renaissance fresco paintings. But whereas Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s sinopie were wildly expressive compared to the more staid trecento forms he painted on the final intonaco layer on top of them, Congdon continues an uninhibited drawing technique in the stencil-made marks on the surface of the work. These stenciled forms instantiate structure as solid bones and brilliant brushstrokes. In Congdon’s working process, stencils taken from one painting seed the next in its turn.

An oblique autobiographical memory pervades these splendid pictures without calling undue attention to the artist’s persona. Congdon’s images are ecstatic, in vivid colors that soak into the canvas and evaporate under the heated gaze of the beholder. Although Congdon was trained in Rome, he gives us classical antiquities in various guises situated in loci more distant and “exotic” than Rome. These canvases bring us to Tunisia or Palmyra (“the land of palms”), the Sinai deserts, and other sacro-idyllic groves. More than in any place in real geography, such congeries are located in the realm of the visual imagination.

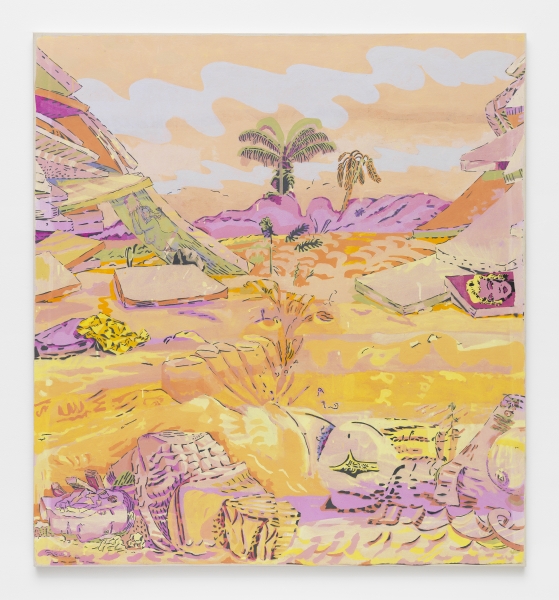

Dennis Congdon, Two Palms, 2015.

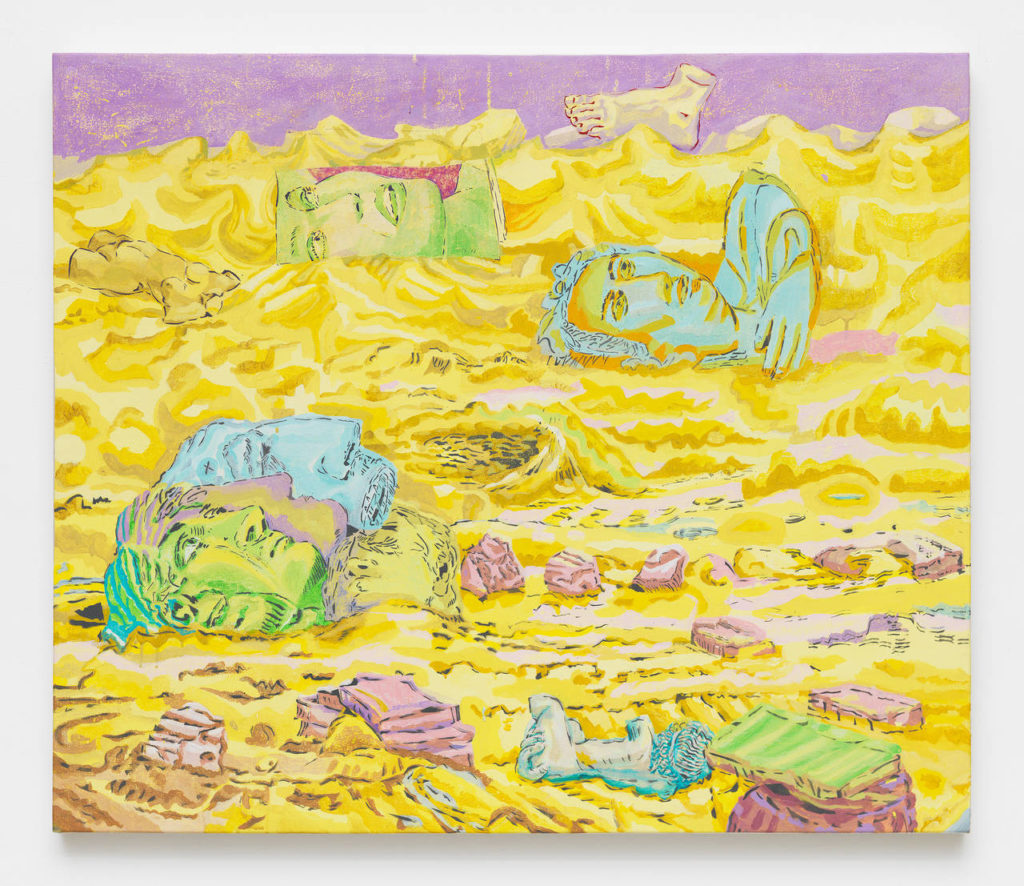

Two Palms is composed with an extraordinarily high horizon. A disembodied foot perched against an untroubled lavender sky gives way to a sea of golden sand littered with the detritus of cultural and personal memory. A scattered upside-down torso “with no face to prevent us from loving it” is painted in the manner of a Cézanne still life, but oddly translucent. A blue fragment of a defunct Roman togato swims through the whirlpools of yellow tides; this swim brings an inanimate sculpture to life in an uncanny manner. Stacks of sculptured portrait heads are seen in profile jutting from the environmental plasma in a lower register, each in it’s own color and state of decay. There are heads, and there are heads: in phenomenological terms, the mental is made manifest in the exterior structure of these broken physical portraits. These objects are not as candid as the blue “swimmer” in the same composition: they are less innocent, although all of these figures are haunted. Two Palms is a landscape in the optical unconscious of art history–not “dark” but mysterious and uncanny to behold.

Dennis Congdon, Caryatid (detail), 2015.

The caryatid of Congdon’s Caryatid hides in a broken canvas. She is a voluptuous, maybe even pregnant, nude holding up a framed mirror and glancing back over her shoulder. She is a personification–a painting about painting (in a painting). What at first glance looks like an empty frame must be a mirror, since painting is the mirror of life and the figure is triumphant. Delicious passages like this reward viewers who take the time to wander in the paintings. Andy Warhol’s portrait of Marilyn Monroe appears (more obviously) at the bottom of a facing landslide of canvases–a relentless echo of the American twentieth century. The lower register of this work is a kind of cipher, with notational marks that don’t exactly add up to figurative representation. Among the detritus is a male portrait head with no emotional inflection, but filled with cubical objects and other unexpected brain matter spilling out; elsewhere an inflated breast finds its echo in the end of a curved volute. Two mighty but somehow wilted palms emerge from a brilliant pink mountain range. A senatorial portrait, an architectural volute, a breast, a palm: in these renditions, nature and culture are fused in Congdon’s imaginary landscapes.

In spite of the vivid horizon in Two Palms, this is not the dawn or sunset of Giorgione’s terra-ferma paradise as inhabited by shepherds and nymphs. Rather we are present in the all too bright and therefore paralyzing noonday hour of Mediterranean sun. The scene is a habitat of broken temples, where only lizards and reanimated statues might dare to wander. Freud’s Gradiva is our guide, and in Congdon’s landscapes we encounter erotic vignettes by surprise, as if they were memories accidentally recalled to vision.[ii] Congdon looks to the father of psychoanalysis for his mode of working in these phantasies in an extended elaboration of Freud’s famous “archaeological metaphor,” where the analytic reconstruction of a patient’s forgotten past is pieced together from fragments excavated in the psychoanalytic hour.

Imagine that an explorer arrives in a little-known region where his interest is aroused by an expanse of ruins, with remains of walls, fragments of columns, and tablets with half-effaced and unreadable inscriptions...He may have brought picks, shovels and spades with him, and he may set the inhabitants to work with these implements. Together with them he may start upon the ruins, clear away the rubbish, and, beginning from the visible remains, uncover what is buried.[iii]

In his own musing over hidden secrets of the past, Congdon remarks that it is all a question of strata and excavation: just under the crust of the earth, he says, live Aphrodite and Antinous in their glorious glowing marble skins of nudity and sexual lure. But such fragments can also be troubled by too much time, love, corrosion, or decay.

Dennis Congdon, Greenwood, 2015.

Greenwood, true to its title, signals a joyous reanimation of objects and hands, bone marrow and brains, plant life and colored glass. A tassel of wheat supports a painting of itself. Flutes and arrises in broken columns are effortlessly symphonic and monumental. Quotes from Matisse are merely musical interpolations in the sky. The protagonists here are hands, hands disengaged from their sculptural origins but full of assertive persuasion. The awkward azure fist in the lower register (paralyzed by its own masculinity?) contrasts a sumptuously articulated rosy hand at the horizon, palm up, with the trunk of a palm slipping through the fingers like a cigarette. The top of that palm is cracked off, and in its inverted position takes the form of a crazy turquoise glass chandelier. Wait a minute–a palm is holding a palm! Could we be in Congdon’s private Palmyra? I suspect so.

The painter speaks of a persistent and feverish Romanticism in the history of art, of empires crumbled and the fragility of life itself. When Congdon goes to Rome he looks at ruins with Hubert Robert, thinking simultaneously of the old stones themselves and the way his predecessor painted them. Similarly, he “listens” for Corot as he draws at the Aqua Claudia. None of this thick study, however, is expressed without a keen sense of humor about the state of painting in the second decade of the twenty-first century.

Dennis Congdon’s life in the studio is a long meditation on the cultural process, where art is made from art and painting is free to engage with any kind of art, whether it be made or merely imagined, from the present or the past. “Simply put, art is always made from other art,” says Congdon, who embraces this idea without apology or fear in the quest of making something new and visually riveting. His canvases follow one another as if measures in a musical score; and as in music, we wait with pleasure for the next refrain.

[i] Among his accolades, Congdon was chosen as a NetworksRI artist for 2016, for which an exhibition at the Newport Art Museum will run from October 2016 through January 2017.

[ii] Sigmund Freud, Delusions and Dreams in Jensen’s Gradiva (1907) SE IX: 7-95.

[iii] Sigmund Freud, The Aetiology of Hysteria (1896) SE III: 189-221.