Since 1895, cultural institutions from around the world have gathered at the Venice Biennale to present the latest developments in their country’s visual arts, performance, and design. With the Biennale attracting over 500,000 visitors last year, prospective contributors vie to present new projects and exhibitions. In 2015, the Art Biennale, focusing on advances in contemporary art, featured 138 artists from 53 countries.

For the 56th and 57th Art Biennale, the U.S. Department of the State’s Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs selected two university museums from the Greater Boston Area to represent America at the U.S. Pavilion. The List Visual Arts Center at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology was selected to commission the last presentation, a much-deserved exhibition by influential artist Joan Jonas, lead by Commissioner Paul Ha, and it was recently announced that in 2017 the Rose Art Museum at Brandeis University will present an exhibition by the L.A. based multimedia artist and social activist Mark Bradford, lead by Rose Director, Christopher Bedford.

In hopes to record this moment, I set out to interview Ha and Bedford for BR&S to gauge what this repeated recognition means for Boston’s local academic, institutional, and curatorial community. I met first with Christopher Bedford in his office at the Rose on May 9th, two weeks after the proposal with Mark Bradford was accepted.

The Rose Art Museum exterior with American and Italian flags. Photo by Sam Toabe.

Sam Toabe: You have worked with Mark Bradford for many years now, curating his first major, traveling survey, and collaborating on several other exhibitions and projects. When was the first time you encountered his work, and when did you realize you wanted to present and contextualize his art through exhibitions?

Christopher Bedford: I was an assistant curator at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, and I was particularly interested in Mid-Century Abstraction, both painting and sculpture. At that point, I understood Abstract Expressionism, painting, and the work of people like David Smith as a strictly historical phenomenon. The idea of being emotive expressively through abstract forms that were fundamentally existential in their address struck me as an impossibility in the present. So a colleague of mine suggested that I go and see Mark Bradford, and at that point, Mark was not the Mark that we know today. He was working in a transitional studio while he was renovating another in South Los Angeles. He'd just been given the Bucksbaum Award at the Whitney before I went to visit him. I remember it being this very narrow studio and I walked into these towering, almost uncontainable silver paintings on either side. The truth is that the genesis of everything was probably that moment of apprehension.

Christopher Bedford and Mark Bradford installing Bradford's 2014 Rose exhibition. Photo by Caitlin Julia Rubin.

ST: What do you mean by "apprehension?"

CB: For me I saw the future for an expressionist painting that I thought was prohibited in the present. If you understand art history as progression—one door opens and another closes—I had felt historically that that door had closed. And by painting with paper and by scavenging materials, and creating a kind of palabres that was expressive as consequence by the way you work them, I saw a next step in Abstract Expressionism. That was kind of a remarkable experience in of itself. I think in that moment I understood that Social Abstraction had been born.

That was really persuasive to me because I want to imagine a world in which art kind of rubs up against the culture we all inhabit. That was key.

ST: When did you first envision this proposal with Bradford for the Venice Biennale? Why now?

CB: I think it has to do with social issues. [However], there are some formal questions. Mark works across media, so he's a painter and a sculptor, and works with the moving image. I felt that I wanted to see painting in the pavilion, and although that's not all that Mark will do, there will be some aspect of his two-dimensional work on view.

The other part of it has nothing to do with the art world, and it has everything to do with the social world. I was thinking about civil unrest in this country and its basis in a collective desire to see racial and economic justice take real root in the way that I think we had all imagined it would in the aftermath of the Civil Rights Movement. The promises of that heroic time have not fully flowered. I think unrest in places like Baltimore is a consequence of that promise not being delivered. I think the domestic context, the call for that justice was key to me.

Brandeis is really invested in social justice. It's a principle that cuts across everything that we do. So as a commissioning entity, I couldn't conceive of anything better than Brandeis, which was another factor. I felt that my seat relative to Mark's agenda felt correct. The refugee crisis world wide I feel is equal and equivalent to the civil unrest in this country. Mark has a transnational reputation, a transnational address with a capacity to address global as well as local. That felt timely to me.

What I have observed of Mark over the last ten years is an increasing commitment to formal innovation in one hand with work in his studio, and then Art + Practice which is his foundation in Los Angeles that that serves transitional age youth populations through art, job training, and job preparedness. So that's flowered as well as his painting has. It felt to me like those two prongs could be mobilized in Venice.

ST: You’ve said that “Bradford creates work that embodies art's capacity to both inspire wonder and catalyze enduring social change.” Considering his work with Art + Practice and his active presence in his local community in Los Angeles, will there be any programming elements that will provide social engagement, activating his practices beyond the studio?

CB: Absolutely and categorically yes. This won’t be a flashpoint in Venice. This will be something embedded in the structure of the city in some fashion that lives way beyond the Biennale. Much like the work Mark did in New Orleans, at Prospect.1. He helped develop a nonprofit there called L9, which founders Keith Calhoun and Chandra McCormick, who are incredible artists in and of themselves, still run. Their historical project, as photographers, has been capturing images of incarcerated people—particularly in Angola Prison—in Louisiana. I would say Prospect.1, and the work he and I did there, was pretty instrumental in his conception of Art + Practice, and the idea of sustainable change through artistic enterprises. So Venice will be a continuation of New Orleans and Art + Practice in a lot of ways.

ST: Does your plan acknowledge the US Pavilion’s past representation of artists from the museum’s collections, and how do you see Mark Bradford’s form of social abstraction to fall in the trajectory of Abstract Expressionism?

CB: Our plan is to produce a truly significant catalogue to accompany the exhibition. Katy Siegel is my co-curator, and she is the co-editor of that catalogue. It will annotate the way we see Mark's practice as an artist living historically.

So yes, there will be nods to the Ab-Ex tradition, but there will also be nods to traditions of panoramic painting in the United States going much further back into the history of art. "What would the American panorama look like today," would be one questions. Or, "What would a mural or public painting tradition in the United States look like in the aftermath of some of the great muralists?

Thomas Hart Benton is a touchstone for me. I don't think that it's incidental that Thomas Hart Benton was Jackson Pollock's teacher. If there is an heir to that kind of painting working today it's certainly Mark, but with a kind of social embeddedness that leans more towards Benton than Pollock. I can say it will be quite different from other Biennale catalogs in that it will go far beyond the scope of the project, even far beyond the art world to look at domestic American history and world history and its relation to race and economics. There will be more historians than art historians, more historians than curators. It will feel much less insider to the art world than is typical.

Mark Bradford in Venice. Photo by Christopher Bedford.

ST: On the website for the project, there is a picture of Mark Bradford in a water taxi, looking toward the Venetian coastline with his camera in hand. Was this taken on a scouting trip for the proposal? Were you on that boat?

CB: I took the photograph! It was taken during a reconnaissance trip that we made on a whim in advance of submitting the proposal. I felt really strongly that he needed to see the site to understand the pavilion and to see Joan Jonas's show to fully take in the possibilities of working in Venice, and walk the city to understand its demographics first hand.

ST: There are many great curators who have mounted exhibitions for the US Pavilion, including giants of the field like Sam Hunter, Rosalind Krauss, Robert Hobbs, Nancy Spector, Linda Norden. How does it feel to be added to that list?

CB: Nobody has posed that question. I would say that for most people in my field it is an aspiration. I can say with real integrity that it feels like an honor to perpetuate the tradition. I think on a personal level, looking back at Sam Hunter's involvement is significant to me, because so much of what I have done at the Rose has been about what he began. If I were to give a synopsis of what his contribution was here, it would be that he was willing to throw out all the models. He embedded himself in the present. That was extremely unusual for museum Directors at that point, and he made a point of befriending artists and allowing them to lead the way. I didn't come here to find that template at all. In fact, I didn't really know that about Sam Hunter until I arrived at the Rose and dug in. That feels personally significant to me. Also, it strikes me as characteristic of really successful curators working with living artists, that you can abandon yourself to their creativity.

That's certainly the case for me with Mark. I think that my own intellectual life is immeasurably enriched by him leading the way. I think Katy would say the same thing. It is one of the reasons why we work well together as co-curators. We're both willing to have our ideas shaped by what we see as opposed to coming to a project with an idea that we then seek verification for. And that is key to working with Mark because he'll always outpace you.

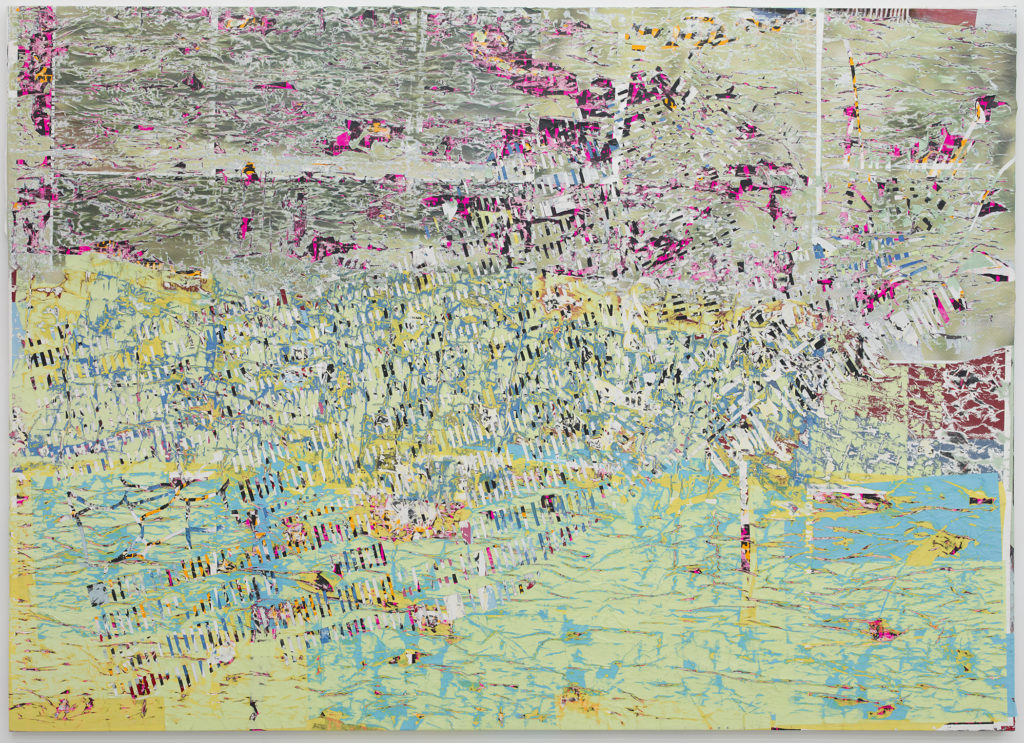

Mark Bradford (American installation and conceptual artist, b. 1961); Father You Have Murdered Me; 2012; Mixed media on canvas; 102 in. x 144 in. (259.08 cm x 365.76 cm); The Rose Art Museum, Brandeis University (Waltham, MA).

ST: You described it a bit there, but can you tell us more about your curatorial process?

CB: With group shows I try to think really broadly, synthetically about meaningful issues across the history of art; the intersect of the social. That's thematic shows, but when it comes to artists, I will try to select those who I believe outpace my own thinking, who I think acknowledge art history and then create a rupture within it. That is what I am after. So that shrinks the group considerably. Mark is a constant inspiration in that sense.

Mark's practice is predicated on materials and embeddedness. It's almost impossible for him to do things remotely. It's almost impossible for him and me to work through a project from beginning to end at a distance. So it does necessitate travel from Boston to Los Angeles, from Boston to Venice, and I think that the best ideas emerge from a kind of casual embeddedness in the context, understanding materially what is appropriate to it. Although we are just in the beginning stages, I would say primary reconnaissance, primary research will be key to our success.

ST: How do you plan to make your mark with this presentation amongst other great showings by Joan Jonas, Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Louise Bourgeois, Fred Wilson, and the like?

CB: I plan to have Mark make his mark, that's my response. I can be a really productive catalyst for him, but that's very specifically chosen language. He is definitely the author. He just needs the fuel and needs to be told when the idea is truly great. That's probably my greatest contribution to what he does.

ST: It is an exciting time in the Greater Boston Area for curatorial practices in contemporary art. Can you tell us what you think this back-to-back representation says about the strength of our local academic and institutional activity in the national and global contemporary art communities?

CB: I've thought about this a lot of course, and actually, I thought about it way before Paul was the commissioner for Joan Jonas, and before I was the commissioner for Mark. So it had to do more with what's specific and different about Boston in the scheme of the global art world or let's say the national art world.

Having lived and worked in Los Angeles, I can say absolutely and categorically that is the home of art schools in this country. [The schools there] have a commitment to professors who have flourishing professional careers providing instruction to artists on the west coast, so it's no surprise to me that they produce the most exciting roster of young artists. I think New York is the home of the commercial art world, and that's indisputable; it's global.

When I came here (to Boston) it became immediately apparent, this is the home of intellectual art history, and it's the consequence of the concentration of the universities. I would say that if the pavilion in Venice is seeking to advance ideas about artists in the present, or culture in the present that feels thoughtful and relevant, it would come as no surprise that a university art museum would be the commissioner. Following that logic, if this is the greatest concentration of universities per capita in the country, and many of the best ones exist here, in addition to the art museums associated with them, then it's not a huge surprise that there would be two commissioners from the same city.

Joan and Mark are of wildly different registers. In Jonas's case, the genius in the proposal was to say "this artist has been germane to so many generations of artists working with the moving image, this is an opportunity to have her work surveyed for a global community."

In the case of Mark, the way he structures his professional life, it joins the painterly tradition of De Kooning with a new kind of social activism that we've begun to see in the art world. What's different about Mark, if you look at somebody like Rick Lowe, they coexist. His work is his activism and his activism is his work. In Mark's case, they're quite different, and that feels like the 21st century. If a university art museum's job is to chart the course forward, then Mark is the natural choice.

ST: Have you met with Paul Ha to discuss his experience? If you plan to do so, what would you hope to learn from him? What would you like to ask Ha about his participation, and curation of Joan Jonas’s exhibition in the 56th Venice Biennale?

CB: Everything, I would like to learn everything. Every mistake he made I want to avoid. He and I have corresponded significantly in the aftermath of the award, but we have not met in person. But the two museums have begun the process of collaborating, so there has been significant wisdom handed down from his team to the Rose team. I think working in Venice and on the pavilion is a very particular animal, and so they have been extraordinarily helpful in literally navigating the waters.

ST: I hope to interview Paul Ha in the next few weeks. Do you have one question in particular that you would like to ask him?

CB: I would love to know whether or not he had the ambition to be the commissioner for the Venice Biennale and found an artist that he found suitable to that purpose, or whether Joan Jonas was absolutely irresistible as the candidate, and that led him to the Venice Biennale? I'd love to know that because I thought it was an inspired choice.

ST: What do you think is relevant about the effect this prestigious exhibition series has on the commercial art world?

CB: There has been a commercial art world since the beginning of time. You can point to any moment. The Italian Renaissance was predicated on commissions, and those commissions were presented by rich patrons and the artists executed masterpieces that we now study. So those two worlds have always been bound. So I don't think personally that we are seeing anything radical or different at all. I think we are seeing a partnership that has existed in perpetuity. Is that dimension of it interesting to me? Not particularly.

But, for instance, Joan Jonas did not have gallery representation before Venice. That is not an insignificant fact, and I think that is a just consequence of the Biennale.

ST: Then it can be seen as a catalyst for institutional endeavors to help wake up the commercial art world and show it who deserves greater representation.

CB: I absolutely believe that. Sometimes these sorts of contexts can perform a kind of corrective action on art history. If she had been written out, it's up to a commissioning entity like MIT to write her back in.

After four years heading the Rose Art Museum, Bedford is set to be the next Director of the Baltimore Museum of Art. He will continue to act as Commissioner for Mark Bradford’s forthcoming exhibition at the U.S. Pavilion’s 57th Venice Biennale on behalf of the Rose. More information for the project can be found at markbradfordvenice2017.org.

In our next interview, I will speak with LVAC Director, Paul Ha, on Joan Jonas’s 2015 exhibition, They Come To Us Without A Word.

This transcription was edited for clarity.