The attitude commonly required of museum visitors is that of a flaneur, moving at a relatively sedate stroll or saunter though the many galleries. Megacities Asia at the Museum of Fine Arts Boston has a more rapid heartbeat, so to speak, than most museum exhibitions—visitors may find themselves exploring at an intensified pace that seems suited to a show devoted to the world's largest and most rapidly-growing cities. In this way, Megacities serves as a vivid postcard of what it is like to navigate a major metropolis. Upon arrival in a new city, travelers consult maps, take note of major buildings, and compare neighborhoods to get the lay of the land. Here, even frequent museum travelers must check their maps to find the sculptural installations made by the eleven international artists included in the exhibition.

Fruit Tree, Choi Jeong Hwa (South Korean), 2014, Fabric, electric air pump, moto, timer, steel frame.

Photo courtesy Choi Jeong Hwa. Copyright Choi Jeong Hwa/Park Ryu Sook Gallery.

Megacities has an extensive footprint, with works appearing throughout the museum and beyond. This curatorial decision was well-conceived, as, in addition to contextualizing the works within an urban environment, visitors are invited to experience the museum’s permanent collection in a new way. Song Dong’s Wisdom of the Poor: Living with Pigeons, presented in the Art of Asia, Oceania, and Africa galleries, is composed of parts of old buildings found in Beijing. This bricolage of urban detritus gains new meaning through its proximity to Buddhist sculptures from the museum’s permanent collection. Wisdom of the Poor seems simultaneously to express nostalgia for the historic urban character of Beijing, and also the necessity of making do with what is at hand. Further afield, the colorful, inflated MEGA fruit tree by Choi Jeong Hwa, of Seoul, South Korea stands adjacent to the Rose Kennedy Greenway, blooming with enormous pears, peaches, and watermelon. Its location connects the MFA to the larger city, and turns the city itself into a museum.

As visitors enter the exhibition through the lower level of the museum, they are greeted by a 16-panel screen with shifting displays of introductory text, images of the artists at work in their studios, and photographs of the artists’ home cities of Beijing, Shanghai, Delhi, Mumbai, and Seoul. The atmosphere of the subterranean space signals a shift in energy from the airy galleries above; the dim lighting and pulsing music in the stairwell feels familiar to the city dweller—a reminder of busy streets, subway platforms, and bustling bars.

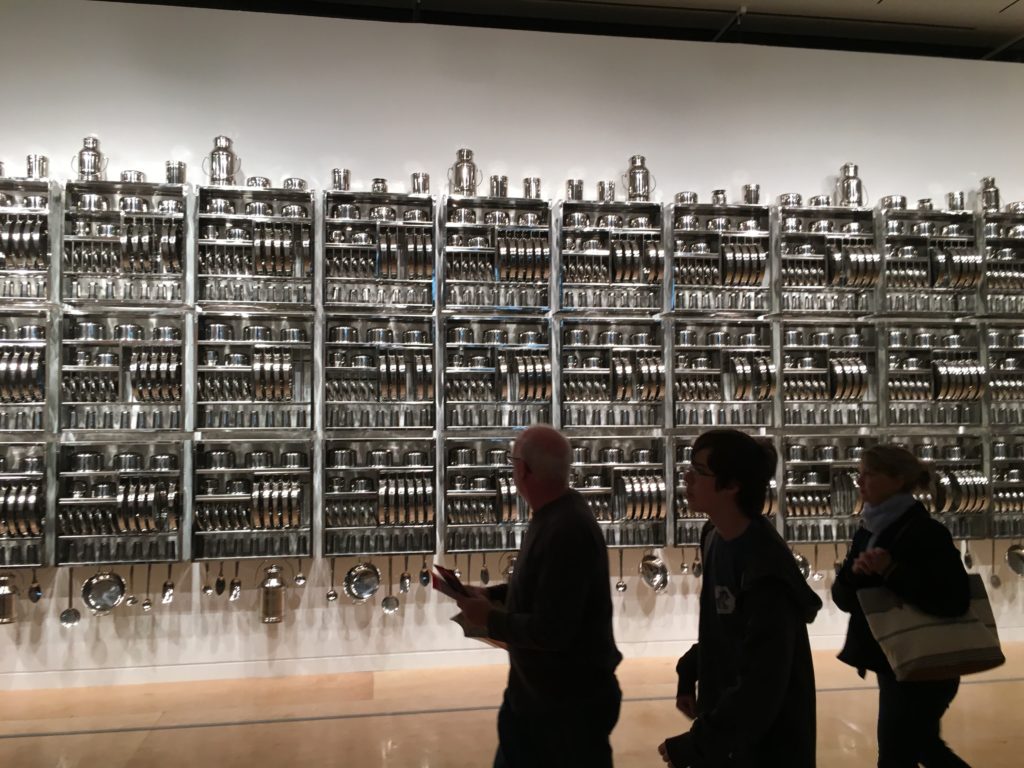

Take off your shoes and wash your hands (detail), Subodh Gupta (Delhi), 2008, part of Megacities Asia at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Photo by the author.

Within the gallery, an impressive flash of metal emanates from a massive bank of shiny brass and stainless steel utensils- Subodh Gupta’s installation, Take Off Your Shoes and Wash Your Hands, annexes the entire width of a nearly fifty-foot-long wall. The repeated, consistent shapes of various pieces of kitchenware calls to mind the modular aesthetic of modernist architecture such as the mid-century structures of Mies van der Rohe. Each individual unit would be a mundane addition to a kitchen in Delhi, where the artist is based, but taken as a whole, the everyday objects (plates, spoons, and vessels) stand as an artillery of organization and preparedness. While the piece speaks of volume—the large numbers of people who populate a city, the power of multitudes, and the presence of hunger and poverty in large metropolises- it is also disassociated from the function of preparing and serving food; the objects hang unused along the wall.

Near Gupta’s installation, Build me a nest so I can rest, by Hema Upadhyay, also uses repetition and scale, but to contrasting effect. A single, equally long shelf stretches the length of the wall, on which stand hundreds of small, found statuettes of birds altered to resemble migratory species. The little creatures perch in twee clusters with a slender strand of typed text in each of their beaks. Observing this work requires pausing to look closely at individual statuettes, while also reckoning with the conglomeration. Each bird is meant to represent a migrant to Mumbai, and the lines of text in their beaks are quotations found online and from print sources that speak in varied ways to the experience of exile in an large, ever-modernizing city. Read from the varied angles from tiny beaks, it is easier to catch phrases rather than entire lines. One reads in part, “Go spend time with the aspen.” Another, “How often I have lain beneath rain on a strange roof, thinking of home.” The birds are a motley flock, and the words they hold are aggregates of human sentiment, while seeming to come directly from nature.

Super-Natural, Han Seok Hyun, Seoul, 2011/2016, part of Megacities Asia at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Photo by the author.

Though similar in their use of scale and repetition, the sculptures in this exhibition also share themes of displacement, immersion, diversity, accumulation, and mass production. By far the most attention-grabbing piece in the exhibition is Super-Natural, by Han Seok Hyun: an installation composed of hundreds of unused commercial objects- all of them green. A shopping bag hanging in the center of the scene is emblazoned with the words “yellow green.” Faux green leaves carpet the floor, giving way to rows of unopened bags of chips. Items with English and Korean text are arranged together in a pleasing sprawl: a paperback volume of Anne of Green Gables, an inflated plastic glove, and packaged baby wipes are all painstakingly arrayed, culminating in tall green brooms which bristle near the top of the arrangement like a triumphant crown. The items are inexpensive and mass-produced, but arranged with a kind of fanatical devotion. Super-Natural seems to imply that urban life breeds longing; a condition that can be sated in the wealthy, but often goes unfulfilled in the poor. The installation unexpectedly draws out these kinds of acquisitive reactions—during my visit, I overheard someone say “I want chips and soda now,” as they appraised bags of green chips and green bottles of soda. Super-Natural makes a heady statement summarizing the awe (for better or worse) of plenty; as many transplants to large metropolitan centers find, choice can be both exhilarating and numbing. This installation has a magnetic effect, and is all the more powerful for being as much a celebration as a critique of advertising and mass production.

The most prominent artist in the exhibition, Ai Weiwei, is best known for his divisive yet memorable pieces focused poignantly on human rights issues. He and Yin Xiuzhen, both of Beijing, authored the two works most openly freighted with clear social critique. Xiuzhen’s Temperature is composed of blocks of rubble studded with bits of fabric arrayed on a large white plinth. The fabric is from found clothing, added by the artist to rubble taken from destroyed Beijing buildings. The blocks of brick and tile are set far enough apart from each other so that they resist a moment of gestalt, where each part may resolve into a single, aesthetically pleasing arrangement. Rather, each piece retains its individuality, reminding us that each fragment was once part of a building. Xiuzhen critiques wholesale construction methods that decimate historic neighborhoods and displace residents, particularly vulnerable artist communities such as hers. The humble blocks, peppered with bright, soft clothing fragments, speak of the dark side of urban development. Nearby, the observant viewer notices Upadhyay’s installation- the moods and messages of the two pieces implicitly intersecting.

Ai Weiwei’s Snake Ceiling stands apart from the central exhibition. It is made of backpacks hanging from the ceiling, strung together in a continuous chain, each unit emerging from the one before it. Snake Ceiling commemorates the children killed in the 2008 earthquake in Sichuan, China, when inadequately constructed buildings collapsed. For something large, elaborate, and seeming to crawl on the ceiling, surprisingly, its power is more conceptual than visual. The scale of the museum overwhelms the simple, familiar forms of the small, unused backpacks. The neat, clean neon green straps and black buckles on these packs are heartbreaking, as they demonstrate a lack of use, emptiness, and voracious hunger.

In the context of globalism, and in an age where contemporary art is often viewed in the neutral booths of art fairs, this exhibition offers specificity of place as a unifying theme. The consistent use of sculptural installation and integration within the museum’s wider collection prescribes phenomenology as a compelling mode of understanding art’s role in our lived experience. Visitors explore as though on a scavenger hunt or perhaps a playground- a wonderful digression from usual museum fare. While visiting this laudable show, I was struck by the number of parents and children winding their way through the maze-like structures. As a smiling father led his son through Venu, Asim Waqif's elaborate responsive environment of rope and bamboo, I realized that for some, this exhibition may represent a sort of homecoming- an opportunity to experience and talk about where they once lived. In communicating our impressions of a place, we often turn to photographs—a medium which is notably absent in this exhibition. The lack of photographs gives Megacities a consistent tone, the artists sharing with us a range of sensations that are all the more potent for their limits. We do not literally view the cities, but the works take our hand and provide tantalizing hints of the numbness and exhilaration, the heartbreak and intimacy, that come from being immersed in a metropolis.

Megacities Asia is on view at the Museum of Fine Arts Boston through July 17, 2016.

- Take off your shoes and wash your hands (detail), Subodh Gupta (Delhi), 2008, part of Megacities Asia at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Photo by the author.

- Build me a nest so I can rest, Hema Upadhyay (Mumbai), 2015, part of Megacities Asia at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Photo by the author.

- Build me a nest so I can rest, Hema Upadhyay (Mumbai), 2015, part of Megacities Asia at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Photo by the author.

- Super-Natural, Han Seok Hyun, Seoul, 2011/2016, part of Megacities Asia at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Photo by the author.

- Venu, Asim Waqif (Indian, born in 1978), 2012, bamboo, cotton and jute rope, tar and interactive electronics (interactive system is triggered by shadows). Collection Galerie Daneil Templon, Paris, Brussels. Photograph copyright Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

- Doors Away from Home — Doors back home, Hu Xiangcheng (Chinese), 2016, featuring reclaimed architectural elements, fabric, photo, and video projection. *BA / YK / MAB Society *Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

- temperature, Yin Xiuzhen (Chinese), 2009-2010, used clothing, rubble from demolished houses, multiple parts. *Courtesy of Pace Gallery. *Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

- Super Natural, Han Seok Hyun (South Korean), 2011/2016, Mass produced products. * Han Seok Hyun *Courtesy of the artist *Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

- Fruit Tree, Choi Jeong Hwa (South Korean), 2014, Fabric, electric air pump, moto, timer, steel frame. Photo courtesy Choi Jeong Hwa. Copyright Choi Jeong Hwa/Park Ryu Sook Gallery.