I followed Robert Chamberlin’s artwork for about a year when his solo exhibition at Miller Yezerski opened in January 2016. I arrived during the peak of First Friday festivities to find an intimate space of the gallery’s rear space packed with people, causing Chamberlin’s installation of delicate, elaborate ceramics to appear all the more dramatic.

Decoration and excess were common themes in the work displayed: in some examples, the clay was frosting-like, with ridges and puffs covering the entire surface of the vase while other vessels sloped at odd at angles, dented in ways that betrayed their origins as soft clay. The vases were all white and ranged in size from four feet to four inches. They stood clustered on large plinths, arranged in an artful disarray that made dozens of vases seem more like hundreds. The ornate vessels were adorned with swags and rosettes made from extruded clay: a clear reference to cakes and pastries.

On a wall leading to the gallery, rows of rectangular plaques punctured at the center with a hole (also all white save for several that incorporated gold), hung in two rows. Most of the holes had an ornate border, but one of them had raw, unfinished edges. In the adjacent back room, a multi-tiered, vertiginous vase held six tapered candles, all of them lit. I was transfixed by the open flames- a rare occurrence in an art gallery. As I stood there, taking in the festive atmosphere, I decided to visit Rob’s studio. I wanted to talk about dangerous beauty, the influence of Baroque forms on his art, and what caused him to blend the sculptural delights of clay and frosting.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

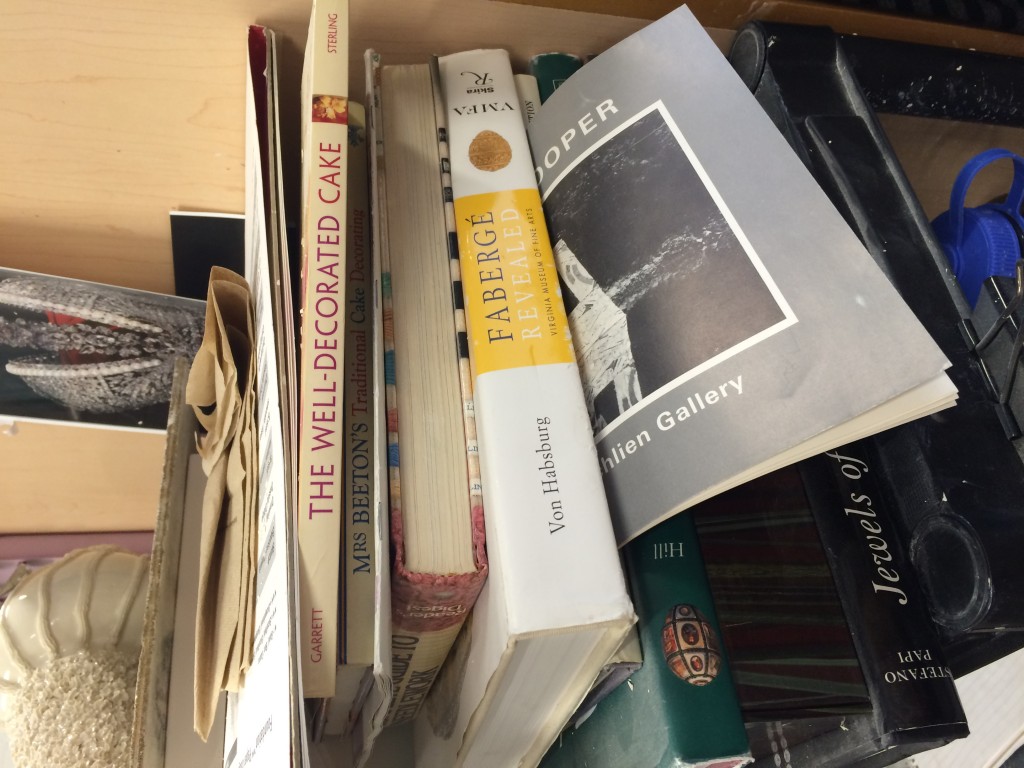

Books in Robert Chamberlin's studio at the Harvard Ceramics Program, Cambridge, in February 2016.

Shana Dumont Garr: I like that there’s a big pile of cookbooks in your studio. Your frosting technique is one of the first things that I had wanted to ask you about. The affinity you create between clay and frosting has a magnetic pull.

RC: I have literally baked in my art– I did a Bake Sale to Meet a Husband in 2012. People I grew up with, who I went to church with, didn’t disguise the fact that they went to college to meet a husband—that is still a thing. I was going to Tufts at the time and decided to do it as well. Women loved the project so much. If they brought me a single, gay friend, I’d give them all the free snacks they wanted. It highlighted the performative aspects of dating and marriage, including men meeting men.

Now, piping (a frosting technique) is my idea of 3-D printing. Part of the effect of the aesthetics of baked goods is referencing ephemerality. That transience is part of my observation of culture: when things are especially ornate, it’s often at times when you know that thing is not going to last which is why I toured the Palace of Versailles in France and the Peterhof Palace in St. Petersburg, as well as related museums. The shapes and designs of my pots are inspired by Sevres porcelain, but my works are different because they are fixed in moments of near-collapse.

SG: Your current work appears ephemeral, but because it is fired clay, it’s not nearly as delicate as frosted cake. Could you speak to that irony?

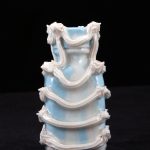

Robert Chamberlin, Approaching Tiffany Blue, 2016, porcelain & mason stain, 2.75"x 1.5"x1".

RC: When you tour a palace, you can observe parts of the restoration or the cracks in the (presented) history. I seek to achieve a similar effect. My work reaches a moment right before it’s about to break—some of my forms protrude in an off-kilter way. I went to a palace in Vienna after having done research on the Hapsburgs, and all of this awful stuff they had done was fresh on my mind. The history was preserved to present an entirely positive narrative. Amid the beauty of the architecture and the Baroque decoration, I sensed the breakage.

SG: When touring these mansions, what are examples of the gaps between the theater and effort that it takes to make it all continue to seem grand, centuries after the dynasties that built them collapsed?

RC: One example is when you get caught up in the perfection, and then notice a sign stating that it’s a recreation. In Germany, a mansion appeared perfect, and it was gorgeous, but it was recreated. I welcome hints of imperfection: It’s an opportunity to remember that it’s all made by people.

SG: I could see you collaborating with a historic home, mirroring part of the collection but then introducing deviations as well, to create a portrait of the aspirations represented by period-specific decoration.

RC: One of my dreams is to do a residency at the Victoria & Albert Museum—they have an entire room with a kiln. Queer historical narratives are always a thread that runs through my work. But in a larger narrative, my work is about collapse in general. An example is Versailles. It represents culture at both the height of and at the end of something. Or in St. Petersburg, Russia, the Romanovs had this amazing dynasty that lasted longer than any other dynasty. By the end, they had Peter the Great, the Winter Palace, and it was so grand, but it was so over.

There’s one piece in my show where I made a larger candelabra. It came about when a piece fell overnight, and I preserved it—a ceramicist would hate this, but I love epoxy, and I stuck two pieces together to make a more complex form.

SG: You wouldn’t call yourself a ceramicist?

RC: I have a conceptual interest in ceramics as it relates to the western history of desire. My training is in analog photography. Also, now, I’m painting through extrusion. I keep thinking I need to apply to painting shows and see what happens.

SG: I can see that some of your greenware (unfired pots) incorporates pastel colors. Tell me about this introduction of color.

RC: I’ve wanted to think about color in my work for a while. I’m working on creating faux marble with a marbling technique and have also recently experimented with pink. The blue is for a new series, “Approaching Tiffany Blue,” which brings up the seeking of perfection in American culture. It comments on a post-AIDS society, where being healthy means something different than it used to in the gay community.

Robert Chamberlin, Light My Fire 59, 2015, porcelain, 8"x6".

SG: Your solo show at Miller Yezerski included a hanging plaque on the left that has a more deconstructed feel. The other plaques all have a neat finish, with extruded piping framing the hole, but it seems like you made one in a different way.

RC: Those plaques are all glory holes.

SG: I totally missed that.

RC: They’re deviant objects, and I think many people miss it. You can get away with so much when you make it decorative. There’s coding of history, or anything, if you dig into things, to get at real meaning. I think about the social, in this case through the glory hole scene in Boston. A close friend and mentor lived west of Boston, and he described a specific meeting area that he frequented. Those visits involved both a sense of community and of fear. That piece you pointed out was me thinking about what a glory hole would actually look like, more utilitarian.

SG: It’s a hint for us who may focus on the superficial, shiny aspects of the works.

RC: They are all hung at the level of my mouth and crotch, which is another hint at their true meaning.

SG: What about the little roses?

RC: They’re also a bodily reference. In the fisting community, when someone has had an extremely arousing event, it’s called rosebudding, and that refers to the appearance of the anus after that event as well. I want to start pushing that level of meaning in my work.

Robert Chamberlin, Light My Fire 90, 2015, porcelain, height approx. 40".

SG: Do the vases also reference the body?

RC: Not as specifically. They become bodily in the way that they’re a weird caricature of a person, with “feet,” “shoulders,” etc. I keep pushing the work so that I’m also curious and not simply fabricating repeated units that I know could sell.

I want to take the work more into the realm of installation. I’ve been thinking about light, and chandeliers, which are functional yet interesting in a space. They’re a whimsical kind of decoration associated with dining rooms. If I wanted to have a conceptual dinner party, how would I light it? With the candelabras, I’m also thinking about memorials and candle-lit vigils. I bring light to heighten the work, also to mourn what’s there currently, as a reminder that this will be gone.

SG: Do you see your work as political?

RC: I guess so? I think I have made more overtly political work, but there is something in my ceramic work of late that is critical. It is political in the sense that I am advocating to not lose a portion of queer history.

There is something to making things beautiful; it's an entry point. Conceptually the work always uses beauty as a front with more hiding behind it. A lot of things that are beautiful are fronts: clever deceptions. In the most recent work from Light My Fire, it was very important to make things beautiful. Some of the pieces in the show, the wall of glory holes, for example, reference something in gay culture that is not a glamorous thing, and because of their ephemeral, secret nature, they will be lost with the oral tradition of an older generation. For some people, that wall will never register for what it is, and in some ways, I want to make it more explicit and less coded. The work has always been about desire- whether it’s a historical desire for the material of porcelain, or my own personal desire.

Detail of Robert Chamberlin's studio at the Harvard Ceramics Program, Cambridge, in February 2016.

SG: Entertainment and relational aesthetics seem to be persistent undercurrents in your work. If budget and time weren’t issues, and if you were to completely execute your vision, would people be involved? At Miller Yezerski, would you have added furniture, if the space allowed?

RC: I had a tea party recently, and would have loved for that opening to be an elaborate tea party. Opening receptions are work, business, networking, and celebrations. In a future event, I would include elaborate, hand-crafted invitations, taking a cue from Vanessa Beecroft, to invite people to a curated social event. I envision a small gathering sorts where there is a theme that conceptually drives the food, decor, and guests. I am also interested in mining history in that regard—connecting with the importance of tea to Boston’s history. An event of that kind would impact people on a personal level.

SG: You're leaving Boston, and I'm so glad we were able to meet before that transition. Could you comment on the move?

RC: First, I'll embark on a four-month road trip across the US with my fiancé, Coorain. We'll work on his video series,Coloring Coorain, and will land in Atlanta in June. A big part of this decision was based on issues of economics and space. My three years as a resident artist at the Harvard Ceramics Program was wonderful but as much as that opportunity supported me, my work has outgrown that space. I anticipate expanding my practice to installations in a larger studio space in Atlanta.

SG: Will you continue to be represented by Miller Yezerski Gallery?

RG: Yes, and a large amount of my artwork is stored with them now. I plan to regularly visit Boston and remain in touch with colleagues, friends, and other relationships I have formed while living here.

SG: It appears that you have a strong impulse to integrate art and life.

RC: The more I try and involve art in my life the better! With that said I know my fiancé, Coorain, and I want to use our coming wedding and lives in our art. For our engagement, we made a video, both as an announcement to family and friends, but also as a collaboration. I made a lot of performance work in graduate school about wanting to get married (living in a state where that would be possible for the first time), including a full-on re-creation of the popular television show The Bachelor. A wedding is a huge performance, and both Coorain and I are interested in performance art. There's an interesting collision here that we'd like to explore. For most people their wedding is like an art show, you get to be creative, and there are lots of aesthetic and conceptual elements to plan for that all represent this relationship and love publicly for your family and friends. We are in the very, very early stages of planning the wedding, (aka we are still picking a date), but the event will be full of Coorain and I and that generally means art!

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Robert Chamberlin has an MFA from the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston/Tufts University and a BFA from the Ernest G. Welch School of Art and Design at Georgia State University in Atlanta, GA. He received the SMFA Traveling Scholar award in 2014 and traveled to Russia, Germany, and Austria to tour ornate, regal palaces. He is represented by Miller Yezerski Gallery, Boston.

- Robert Chamberlin, Marble Test 1, 2016, porcelain & mason stain.

- Robert Chamberlin, Porcelain Rosettes, 2016, porcelain. Studio test.

- Robert Chamberlin, Approaching Tiffany Blue, 2016, porcelain & mason stain, 2.75″x 1.5″x1″.

- Robert Chamberlin, Light My Fire 90, 2015, porcelain, height approx. 40″.

- Detail of Robert Chamberlin’s studio at the Harvard Ceramics Program, Cambridge, in February 2016.

- Detail of Robert Chamberlin’s studio at the Harvard Ceramics Program, Cambridge, in February 2016.

- Robert Chamberlin, Light My Fire, Installation view, Miller Yezerski Gallery, January 8- March 15, 2016.

- Books in Robert Chamberlin’s studio at the Harvard Ceramics Program, Cambridge, in February 2016.

- Robert Chamberlin, Light My Fire 59, 2015, porcelain, 8″x6″.

1 Comment

Pingback: Robert Chamberlin Featured in Big Red & Shiny Magazine | Miller Yezerski Gallery :: Contemporary art in Boston, MA