“Part of what fascinates us when looking at a map is inhabiting the mind of its marker, considering that that particular terrain of imagination overlaid with those unique contour lines of experience.”

- Katherine Harmon, You Are Here: Personal Geographies and Other Maps of the Imagination

One year ago, during the snow-laden winter months that brought over eight feet of powder to the Boston-area, I found myself at the North Shore Mall. Desperate the make the trip as quick-lived as possible, I headed towards the directory map. There, next to a giant red dot in big, bold letters, were the words that would influence my proposal for the New Art Center’s Curatorial Opportunity Program submission: YOU ARE HERE. I walked away from the kiosk thinking about the phrase and how subjective the interpretation of “here” really is. Directory maps, like the one in the mall, are intended to orient and help navigate people within public places, but how we interpret place is an unpredictable variable.

The diverse ways in which place can be read made for an exciting exhibition concept. Choosing a venue for the exhibition played a particularly vital role in seeing You Are Here come to fruition. Part of my curatorial vision for the show was to counter the aesthetics and functionality of the “white cube”. To tell the story I envisioned, You Are Here required me to think about space as an active participant in constant dialogue with the work on view, not merely just a place to house it. This presented a set of new, exciting challenges for me to work through.

I first visited the New Art Center in Newton shortly after relocating to the Boston-area in 2013. While I attended for an exhibition opening (truth be told) I spent more time looking at the architecture of the renovated nineteenth-century Universalist Church than viewing the show. There was a kind of beautiful counterbalance between the old and new aesthetics of the building. For example, six original stained glass windows lined two walls of the main gallery. On the adjacent wall, the largest stained glass window occupies almost the entire facade of the church. This one was reconstructed after the 1938 hurricane shattered the original and destroyed the wood belfry and steeple. I later learned that the Gothic Revival style church also served as Newton Junior College and a dance academy all before the non-profit New Arts Center moved there in 1977.

You Are Here was conceived in excitement and enthusiasm over the building itself. With so much history wrapped up in its walls, there could never be just one interpretation of “here”. For this reason, the New Art Center seemed like the perfect counterpart to the You Are Here exhibition concept. In March of 2013, You Are Here was selected as one of four proposals through NAC’s Curatorial Opportunity Program (COP), an open-call curatorial platform that investigates contemporary culture through the visual arts. The program is a rare gem in the New England region in that it provides institutional, administrative and financial support for diverse curatorial visions.

I appreciate the selection committee’s open-mindedness to greenlight an exhibition proposal where more than half of the work was site-specific. On paper, it is a hard to communicate how an artist could use their practice to re-image and respond to a place. As previously mentioned, I had particular interest in how the site that the housed the exhibition could function as more than a venue. I wanted to make the “here” of the New Art Center a source of inspiration for each of the artists involved. Exhibiting artists Darek Bittner (Portland, ME), Dan ReRosato (Philadelphia, PA), Kevin Frances (Boston, MA), Mark Hoffmann (Salem, NH) and Emma Hogarth (Providence, RI) present place as physical, liminal, or psychological spaces, demonstrating that “here” can be both physical and conceptual geographies.

Emma Hogarth and Mark Hoffmann created site-specific installations that responded directly to the physical space of the New Art Center. Hogarth’s projected environment, “Compound Vision” destabilizes the viewer's relationship to place while highlighting the building's architectural elements. Hogarth’s immersive video field entangles physicality, memory, and history of place. It is a portal through which the viewer observes past and present moments colliding. Hogarth created custom software that simultaneously loops pre-recorded footage of the interior of the New Art Center and a live stream, cross-fading the images together. This creates an immersive, disorienting field that is (sometimes) slightly out of sync with reality.

Mark Hoffmann, Holy to Holey, site-specific mural, 2016. Courtesy of Samara Pearlstein.

Similarly, Mark Hoffman reinterprets the building's history in his mural, which references archival documents dating back to 1976. Hoffmann’s site-specific mural, “Holy to Holey” is the result of several months of archival research into the history of the New Art Center’s nineteenth-century church. The mural's central figure has a thumbprint for a face. Each whorl and swirl, like that of a fingerprint, distinctly defines the identity of the building. On either end of the figure, Hoffmann depicts a pivotal moments or characteristics of the building’s past and present. On the left, wind patterns from the 1938 hurricane reference the storm that destroyed the church's original bell tower. On the right, Hoffmann paints intertwining pipes, a favorite feature of the building’s basement as seen on a walking tour of the building.

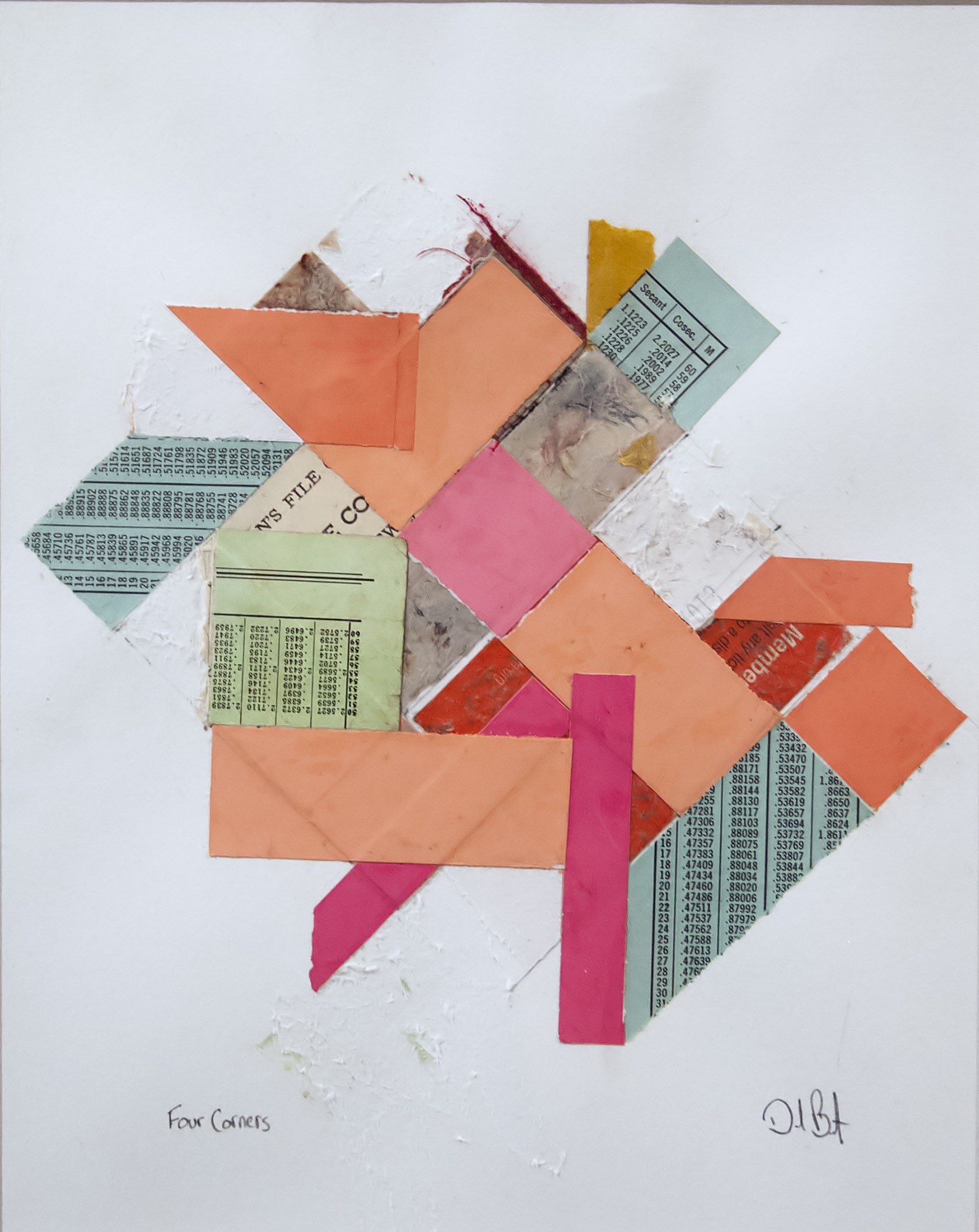

Darek Bittner, Four Corners, collage 2015. Courtesy of Samara Pearlstein.

Moving beyond the New Art Center, Dan DeRosato, Kevin Frances, and Darek Bittner explore the liminal and psychological qualities of place. DeRosato uses the digital technique of glitching, a short-lived fault in a video system’s coding, to create the illusion that a particular place is breaking down or being pulled apart. For “Gallery”, DeRosato glitched self-shot footage of the New Art Center’s interior during the first day of install. Using this program “hack”, the artist prolongs each tiny blip of video damage to compose large, abstract color fields. DeRosato's videos, as well as Frances's installation, throw the viewer into a dance between perception and imagination as the ordinary sites they present slowly come undone. Frances’ installation draws connections between the home and set design, specifically how the objects around us are “props,” physical indicators that convey their owner’s personality, interests and contribute to a larger narrative. From afar, "Our Bedroom," installed on a stage in the gallery, looks real. When entering the installation, however, it becomes clear that everything is not as it appeared to be. A rug is made from silkscreened paper or a dresser is built from foam core. Combining flat 2D prints and 3D sculptural objects, Frances creates the illusion of a place that is neither here nor there. For Darek Bittner, place becomes a psychological construct in his collaged mental landscapes that compile memories from multiple places gathered into one composite view. His abstract collages are inspired by High Peaks, a region of New York’s Adirondack Park. Yet, he also insists that they represent a psychological mindset as much as a physical location. Memory may guide Bittner’s assemblages but he ultimately aims to create a composite of places encountered and the sensations he felt there. His compositions invite the viewer to make associations with their own memories and connections to place.

I’ve been asked on several occasions how I feel the show is being received and I always answer the same way: through the voice of audience members who have related to the show. A standout reflection came from Jim Cusano, a volunteer docent at the New Art Center. He approached me at the opening reception, full of excitement, sharing that he was a student at Newton Junior College and acted the lead in the school play set on the very stage occupied by Frances’s “Our Bedroom on Westminster Street." Jim relayed this memory and others, saying that he said he felt came flooding back due to Frances’s installation begging its audience to physically roam and engage with the stage.

Recently I moderated a conversation with four of the exhibiting artists during a panel discussion entitled “How We Got Here.” A quarter of the way through, the panel organically shifted gears and the audience took hold of the program. They spoke directly to each of the artists, describing their experiences encountering their work, how they felt it worked with the space, and the excitement they felt reconnecting to a site that (some) walk through every day. I sat, silently, in appreciation, realizing that the scope and format of each of the artist’s work reintroduced the space to the NAC community. A particularly special moment for me was to hear from one woman that You Are Here felt “made specifically for the people and community that love the New Art Center.” For me, that was the moment where I felt the impact and energy that site-specificity could have not only on a space, but the people that step inside it.

Kevin Frances, Our Bedroom on Westminster Street, screen prints, masonite, wood, foam core, 2012. Courtesy of Samara Pearlstein.

Together, the pieces on view in You Are Here ask the viewer to consider how they interpret place; whether in the context of shared and personal memories, imagined and reimagined histories, or varying states of construction or disarray. My intention dating back to that first night in the mall when You Are Here was initially conceived was to make this exhibition about interpretation of place. As the process unfolded it became evident that You Are Here was also about the artist’s and audience’s experience and relationship with the New Art Center specifically. I am most proud of the ways in which five radically different artists brought a piece of themselves into the New Art Center, let the place itself influence the product of their work, and as result, help reconnect the New Art Center’s community, staff and students with the place itself.

Curated by the author, You Are Here is on view through March 26.

- Darek Bittner, Four Corners, collage 2015. Courtesy of Samara Pearlstein.

- Kevin Frances, Our Bedroom on Westminster Street, screen prints, masonite, wood, foam core, 2012. Courtesy of Samara Pearlstein.

- Installation view, You are here, 2016. Courtesy of Samara Pearlstein.

- Mark Hoffmann, Holy to Holey, site-specific mural, 2016. Courtesy of Samara Pearlstein.

- Emma Hogarth, Compound Vision, site-specific video installation, 2016. Courtesy of Samara Pearlstein.