“Subtle, persistent revolt” is how GRIN owners and curators Corey Oberlander and Lindsey Stapleton describe their latest exhibit, Besides, on view through February 13. This succinct phrasing suggests small-but-continuous acts of resistance. The second installment in a two-part arc that began with November’s Again Again, Besides features five artists physically engaging in everyday actions meant to preserve individuality. The efficacy of these efforts is questioned, though straightforward critique is mostly absent. The artists focus on tailoring their own idiosyncratic responses to contemporary monotony.

But where does the individual act of dissent stand in relation to failure-prone social movements? As Julia Kristeva asks in The Sense and Non-Sense of Revolt: “Can one recapture the spirit [of revolt]itself and extricate new forms from it beyond the two impasses where we are caught today: the failure of rebellious ideologies, on the one hand, and the surge of consumer culture, on the other?”

Besides answers in the affirmative—mostly. One exception is Allison Baker, whose contributions grittily relay the inescapability of repetitive living. In the video Smother, an anonymous woman smashes a pile of pies with a “pillow” as heavy as a rock. The large stone lands ungracefully each time with a thud as pie filling oozes onto a carpet. Hidden behind a princess pink air vent, the installation is instantly reminiscent of Martin Boyce’s Ventilation Grills (2010), a similar use of an otherwise bland architectural feature. Smother’s appeal, though, is in its pained interactivity. To properly experience the video, you have to hunch over and stare downward, your vision partially blocked by the vent.

Baker plots against the most change-averse institution of all: the home. The artist explains in an interview on GRIN’s website: “The figure [in Smother]is so habituated in the domestic that any transgression is still imagined within the scope of femininity. Pointless sublimation.” The pulverized pastries are the harvest of an impossible revolution. In Spoiled Rotten, meanwhile, Baker hosts a party with no presents. Gift wrap, glitter, and metallic shred are continuously unearthed in the five-minute video, all to an excruciating soundtrack of the tightly wrapped surfaces being ripped apart.

Baker’s video reverberates with a nauseating stream of crinkles and crunches, but hers is not the only sonic intervention here. Eddie Villanueva’s untitled guitar installation consists of a repurposed kiddie ride that spits out a Beatles song. “It disrupts the silent contemplation of art with its jarring start,” Villanueva writes. The idea for this coin-operated sculpture was gleaned from Villanueva’s childhood, when his mom, in between working two jobs, would shuttle him and his sister from school to daycare. The one-hour interim was often spent at Chuck E. Cheese’s, a spectacular and needed respite for the entire family.

“My mom would plant herself in front of this eight-foot animatronic dog that sang Elvis songs,” Villanueva says. “I vaguely remember her sitting alone in her work clothes, in a mostly empty Chuck E. Cheese on a weekday afternoon, sipping on a soda.”

Keegan Grandbois, Halloween Costume Idea #1, 20 x 30, 2015

Unlike Villanueva’s moving mixture of “spectacle” and recollection, Keegan Grandbois’ photography is borne out of appropriated nostalgia. In the endearingly odd and memorable self-portrait, Halloween Costume Idea #1, Grandbois covers his face in Kraft singles, his eyes and beard peeking through holes of processed yellow. “He chooses things that, for the most part, he didn’t have any personal experience with growing up,” Stapleton says, calling it “an act of boredom.” Grandbois channels this ennui into humble subjects—an eggplant and a pipe cleaner, or a tower of chocolate wafers—to impressively formal and vibrant results.

An assortment of home goods also forms the basis of Jessica Lawrence’s installation, The Consciousness of Our Intimacies. A table too low to function is matched with an empty cup, coaster, and three prints, one of them teetering on the edge of the dysfunctional furniture. Lawrence purposely deviates from recognizable forms to “reveal new or unexpected facets of a familiar object.” Her tableau is uncanny: unidentifiable but somewhat remembered, so that the viewer can construct “a self-directed narrative…Something should come of all these objects together,” Lawrence says.

The revolt in Besides is not flashy, climactic or explosive. It is not even, Stapleton asserts, necessarily critical. In an interview with Nou Magazine, Grandbois echoed this sentiment when discussing his own work: “Because the content tends to lean towards the familiar it has the quality of provoking criticism, but I try not to make that a part of the work. The way pop culture is its own entity… [It’s] something that people interact with on an individual level. I try to work with that relationship.”

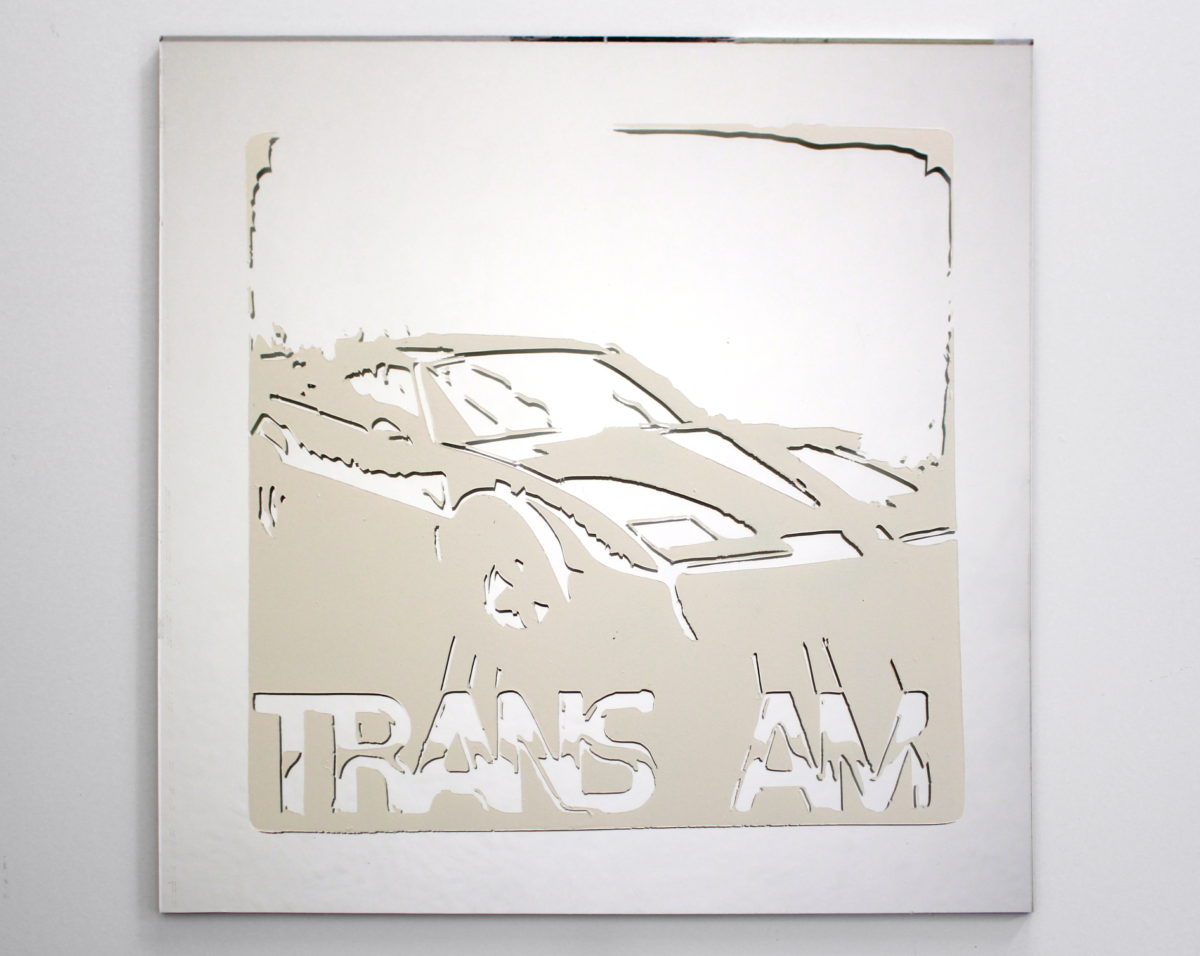

Villanueva also examines this dynamic in his series of painted mirrors. The series is another callback to his childhood and similarly centered on blue-collar amusements. Here he remakes mirrors won in carnival games, replacing the garish palettes of the originals, and redoing the adolescent imagery in a clinical white. The viewer gazes into the mirrors, only to lose their reflection amongst band logos and cartoon characters. In an undiscerning looking glass, one is free to craft an identity—but only with the materials provided by culture.

Villanueva also examines this dynamic in his series of painted mirrors. The series is another callback to his childhood and similarly centered on blue-collar amusements. Here he remakes mirrors won in carnival games, replacing the garish palettes of the originals, and redoing the adolescent imagery in a clinical white. The viewer gazes into the mirrors, only to lose their reflection amongst band logos and cartoon characters. In an undiscerning looking glass, one is free to craft an identity—but only with the materials provided by culture.

“They are very much indicative of a working-class aesthetic of surrounding oneself with cheap things that sparkle, shine, and reflect in order to surround the suggestion of a more affluent place,” says Villanueva. He links his work to social realism, whose historical component seems a prerequisite for any successful uprising.

As Kristeva notes, rebellion must be well-nourished: “There is an urgent need to develop the culture of revolt starting with our aesthetic heritage and to find new variants of it,” she writes. Sandra Erbacher’s Lina certainly fills the criteria for variance. Using the ubiquitous chipboards of IKEA furniture, Erbacher ditches the instruction manual for more radical “Swedish” design. The resulting objects scarcely transcend the banality of their origins, exemplifying what Oberlander and Stapleton describe in their curatorial statement as an “anti-joke…[with a]lack of punchline.” Erbacher’s wall-mounted shelf, however, is sweetened by the inclusion of a wimpy cactus, its growth and livelihood seemingly unimpeded by the tangled schematic it calls home.

Content with its modesty, Besides opts not for an earthshaking rearrangement of domesticity, but a playful aside of what might be possible under the current terms of home life. The most powerful revolts rise not from abstract, ahistorical reasoning, but intimate, first-hand experience.

“This revolt is under way,” Kristeva writes, “but it has not yet found its voice, any more than it has found the harmony likely to give it the dignity of Beauty. And it might not.”

Maybe it has. Before leaving the gallery, I approach Villanueva’s guitar and hesitantly feed it a coin. With the plop of a quarter, my attention shrinks to the rumbling motion of the kiddie ride as it lacerates the air with music. A growling C chord leaps from the amplifier, electrifying the air with a memory aching to be realized. For about 20 improbable seconds, the gallery becomes a Chuck E. Cheese’s, heard through a mechanized strum, and glimpsed in the wobble of an absurd but hopeful instrument.

- Eddie Villanueva, Untitled, Assemblage, 2015

- Eddie Villanueva, Carnival Mirror

- Keegan Grandbois, Halloween Costume Idea #1, 20 x 30, 2015

- Sandra Erbacher, Lina, 2015, Laminated chipboard 37 × 41 × 68 in

- Jessica Lawrence, The Consciousness of Our Intimacies, Installation, 2015