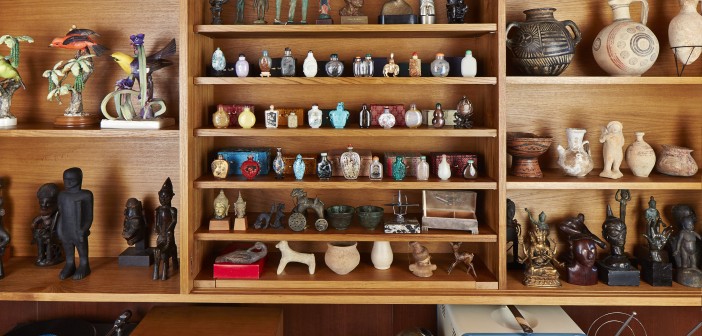

To step into The Undisciplined Collector, Mark Dion’s new permanent installation at the Rose Art Museum, is to enter a time capsule that has seemingly preserved the atmosphere of the institution’s founding year, 1961. The warm glow of lamplight cast on wood paneling offers an unexpected respite from the cool white walls of the galleries. The small, narrow space is arranged like a collector’s room with mid-century modern décor and objects from varying eras and geographic locales. Along one wall, paintings and prints dating as far back as 1603 hang salon-style above a retro sofa and end table. Across the room, a group of cabinets house a strange assortment of treasures, including sculptures dating from the Byzantine era, athletic trophies, and an impressive collection of Chinese snuff bottles. In another corner, a fully stocked liquor cabinet rests atop a wooden flat file, each drawer of which yields another layer of material culture: medallions, correspondences, and rare Japanese prints. Permanently installed on the entry level of the museum, Dion’s installation provokes curiosity, wonder, and confusion, offering a window into the history of the Rose and its eclectic permanent collection.

The year 1961 (coincidentally also Dion’s birth year) was characterized by significant social, political, and cultural shifts. In the United States, John F. Kennedy had just taken office, the civil rights movement was underway, the increasingly popular television set offered new forms of entertainment, and the post-World War II consumer culture was thriving. The evolving values of Americans signaled a change in the art world as well.

For instance, Claes Oldenburg’s 1961 manifesto I Am For… defines the fundamental ideas behind the then burgeoning Pop Art movement and its preoccupation with mass media, everyday objects and commercialism:

I am for an art that embroils itself with the everyday crap and still

comes out on top. . .

I am for US Government Inspected Art, Grade A art, Regular Price art,

Yellow Ripe art, Extra Fancy art, Ready-to-Eat art, Best-for-Less art,

Ready-to-Cook art, Fully Cleaned art, Spend Less art, Eat Better art, Ham

art, pork art, chicken art, tomato art, banana art, apple art, turkey art, cake

art, cookie art.[1]

In this climate of social, cultural, and artistic change, the Rose’s founding director Sam Hunter traveled to New York City where, equipped with a modest stipend of $50,000, he began to build the Rose’s collection of contemporary art. Favoring the artists at the center of Pop Art, Hunter acquired works from Oldenburg, Roy Lichtenstein, and Andy Warhol.[2] These early purchases served to establish the Rose as a space for the study and appreciation of modern and contemporary art.

There is, however, little sign of Hunter’s shrewd eye for collecting contemporary art in The Undisciplined Collector. In fact, nothing in the strange room postdates 1961, save for a few pieces of custom-built furniture, commissioned by Dion to reflect the designs of the time. For roughly two years, the artist worked with a team of museum staff members, scouring the archives and storage rooms of the Rose to unearth ancient Egyptian figurines, engravings dating from the Renaissance, and a small circular portrait attributed to Rembrandt. Other objects were pulled from collections across the Brandeis University campus, including the library’s special collections, the Anthropology Department, and the Classics Department. The result is a curious amalgamation of material culture that ranges from rare gems of antiquity to more bizarre items like matchbooks and plastic swizzle sticks.

Mark Dion, The Undisciplined Collector, 2015. Courtesy Rose Art Museum, Brandeis University; Rose Art Museum Special Fund. Photo Credit: Charles Mayer.

The depth and breadth of the University’s holdings and the idiosyncratic nature of collecting institutions (a result of the varying tastes and inclinations of different curators, directors, donors, and collectors) is precisely what piques Dion’s curiosity. The discoveries he and his team of professionals made when exploring the storage room upset his “perception of the Rose as a modernist temple of challenging contemporary art.”[3] By including these rarely seen objects from the museum’s permanent collection, Dion addresses the often-overlooked fact that “collections are driven by individuals; they develop through quirky subjective tastes and preferences, rather than an objective scientific process.”[4]

Dion has reimagined the cast of collectors, curators, trustees, and donors that individually contributed to the collective holdings of the University as a single person with an eclectic, “undisciplined” approach to building a collection. Despite the heterogeneous selection of objects on view, the unnamed collector has transformed potential chaos into a meticulously assembled display. The arrangement and order may at times seem arbitrary, but one gets the sense that careful deliberation went into the selection and positioning of each object. There is an aesthetic appeal in certain groupings that leads the viewer to speculate on potential conceptual linkages.

This style of display, with its glass-fronted shelves packed with artifacts, calls to mind wunderkammer (or cabinets of curiosity) of the Renaissance. Their contents were displayed in an encyclopedic fashion, not adhering to the clearly defined academic disciplines that were conceived during the Enlightenment. Instead, wealthy collectors of the time gradually accumulated objects “that could be touched and rearranged poetically to produce a kind of awe that could enlighten the mind, delight the senses and encourage conversation.”[5]

The Undisciplined Collector certainly follows this model of display; objects of art, natural history, archaeology, and popular culture are presented side by side, unified in one installation rather than being separated into distinct categories. And, like the curiosity cabinets of the past, the drawers and vitrines here offer no helpful wall labels. The installation’s lack of historical context, coupled with Dion’s interdisciplinary approach to organization, questions established modes of curation and what the artist refers to as “the rhetoric of display.”[6] Without artist names or dates to locate the objects in their historical contexts, viewers are left to make their own connections. What is implied by a porcelain teapot positioned next to a Hopi doll? How does Walt Disney’s autograph inform a letter written by American painter John Singer Sargent? Perhaps there are associations at work here that are not immediate but require contemplation and a bit of imagination. This contrasts the current trend of overly didactic wall text often used in institutions where, as Dion explains, although “exhibits are strong on concept they often fail to inspire, since they ask as well as answer the questions.”[7] In The Undisciplined Collector, the viewer is not a passive recipient of information, but is instead offered the role of wanderer, explorer, and detective.

Mark Dion, Undisciplined Collector, 2015. Courtesy Rose Art Museum, Brandeis University; Rose Art Museum Special Fund. Photo Credit: Charles Mayer.

Dion calls attention to subtle threads of narrative and fiction in the art museum by exaggerating the presence of each. At the entryway to the collector’s haven, a trench coat and feather-trimmed fedora wait expectantly on a coat rack, as if their owner might appear from “offstage” at any minute to fetch them before hurrying away to an appointment. Tucked in the back corner, a locked door marked “Collection Storage” in gilded letters gives the appearance of a fake door in a stage set. The furniture, barware, ashtray, vintage records and television set could all be read as scenery—props necessary to create a backdrop for the collector’s world. The set invites viewers to explore and conjecture, activating the imagination and allowing a sense of play in the museum.

On the other hand, the inclusion of these “exhibition props”—common household objects, electronics, and items of popular culture from the 1950s and 1960s—could also be read as a nod to the Pop Art movement that so critically informed the future of the Rose in its founding years. Once installed within the walls of an established art institution, every object, ranging from a Doris Day record to a September 1961 issue of The New Yorker, is ascribed new historical relevance and institutional value. The status of a retro cocktail shaker is heightened by its proximity to precious archaeological artifacts and works by Picasso and Magritte. Like Warhol and Rauschenberg, Dion confuses the line between low and high culture, elevating everyday items and media icons to the realm of fine art and challenging the hierarchy of objects that is determined by museums.

The Undisciplined Collector is not a disparaging criticism of museums that cling to potentially outdated approaches to curation and display. Rather, it teases at the seams of these established practices, spilling out their contents and exposing flaws and shortcomings. Dion’s installation offers fresh and inventive approaches to the task of displaying a collection that aim to show rather than tell, allowing viewers to entertain questions and curiosity, draw their own conclusions, and ultimately experience an authentic encounter with art.

The Undisciplined Collector is permanently on view at the Rose Art Museum. The museum will reopen to the public on February 12, 2016, with an opening for all Spring 2016 exhibitions on Thursday, February 11, 5-9pm.

[1] Claes Oldenburg. “I Am for an Art: Claes Oldenburg on His 1961 ‘Ode to Possibilities.’” Walker Magazine, September 20, 2013. Accessed December 19, 2015. http://www.walkerart.org/magazine/2013/claes-oldenburg-i-am-for-an-art-1961.

[2] David E. Nathan. “Sam Hunter, Rose Art Museum's first director, dies.” BrandeisNOW Weekly, July 29, 2014. Accessed December 17, 2015. https://www.brandeis.edu/now/2014/july/hunter-obituary.html.

[3] Mark Dion. Interview with Caitlin J. Rubin. 2015.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Lisa G. Corrin. “A Natural History of Wonder and a Wonderful History of ‘Nature,’” in Mark Dion, ed. Mark Dion, Lisa G. Corrin, Miwon Kwon, and Norman Bryson (London: Phaidon, 1997), 52.

[6] Mark Dion. Interview with Caitlin J. Rubin. 2015.

[7] Mark Dion. “The Natural History Box: Preservation, Categorization and Display,” in Mark Dion, ed. Mark Dion, Lisa G. Corrin, Miwon Kwon, and Norman Bryson (London: Phaidon, 1997), 137.

- Mark Dion, The Undisciplined Collector, 2015. Courtesy Rose Art Museum, Brandeis University; Rose Art Museum Special Fund. Photo Credit: Charles Mayer.

- Mark Dion, The Undisciplined Collector, 2015. Courtesy Rose Art Museum, Brandeis University; Rose Art Museum Special Fund. Photo Credit: Charles Mayer.

- Mark Dion, The Undisciplined Collector, 2015. Courtesy Rose Art Museum, Brandeis University; Rose Art Museum Special Fund. Photo Credit: Charles Mayer.

- Mark Dion, The Undisciplined Collector, 2015. Courtesy Rose Art Museum, Brandeis University; Rose Art Museum Special Fund. Photo Credit: Charles Mayer.

- Mark Dion, Undisciplined Collector, 2015. Courtesy Rose Art Museum, Brandeis University; Rose Art Museum Special Fund. Photo Credit: Charles Mayer.