I spent the latter half of my childhood in a small town in eastern Connecticut. Once it had been strictly rural, but by the latter half of the twentieth-century was slowly succumbing to the inevitable creep of suburbia. For the time I lived there the countryside barely held its ground. Roadways had been punched through the town green; subdivisions gnawed at farms and meadows. The town’s first supermarket opened shortly after we moved there, just down the street from the town’s sole traffic light. Still, there was a cow pasture across from our house; deer and grouse roamed the woods behind. The elementary school and the church where my father worked were equidistant from home, each a stone’s throw through the trees.

The church was of little historical interest. The parish had moved to a more central location in town during the mid-eighteen-hundreds, leaving the old burying ground to an overgrown and under-appreciated anonymity. In the much larger new cemetery, amid Civil War veterans, a state Governor, and the town’s lone Vietnam war fatality, were two small limestone headstones, one a foot tall at most, the other slightly taller and thinner. Both were badly eroded by years of acid rain; by now they must be completely illegible. I might have trouble, were I to go back there today, in locating many graves, including those of friends and acquaintances, but these two unremarkable stones remain fixed in my memory. Carved into the top of the smaller stone were the words "Little Orvie;" across the face of the other, "The Orphan’s Friend."

To be buried without a name is a rarity in this age and country, but was long commonplace. Paupers and unknowns were consigned to the potter’s field and unmarked graves; permanent memorials were reserved for the wealthy and powerful. This person and his friend—or a faithful pet, a dog, perhaps, buried next to its owner in a burst of Victorian sentimentality—left nothing behind but a testament to a relationship. Not much, but more than most tombstones convey even now. For whom were these stones meant- by which I do not mean who is buried there, but who was meant to read them?

Pick your favorite actors and put them to work:

Hamlet: . . . Whose grave’s this, sirrah?

. . . What man dost thou dig it for?

Clown: For no man, sir.

Hamlet: What woman then?

Clown: For none neither.

Hamlet: Who is to be buried in’t?

Clown: One that was a woman, sir; but, rest her soul, she’s dead.

(William Shakespeare, Hamlet, Act V Scene 1)

The limits of memory are omnipresent. I might have recalled these lines verbatim, though I didn’t, and the essential meaning of the scene is colored by my imperfect remembrance. In recalling the actors I have seen play Hamlet I know also that my memories are questionable. Each role is a synthesis of the author’s words overlaid with layers of context: The actor’s ideas, the director’s, the current state of thought about what constitutes good acting, good film-making, and so on. Let’s set aside the fact that there is no definitive text of Hamlet; the standard text is an amalgam of several sources. I imagine I know how the part was played; I know I imagine things that were not so. In my mind I cast John Barrymore as Hamlet. Of his performance, only still photos, a few audio recordings and a tantalizing screen test in the pale hues of two-strip Technicolor exist. From seeing him in other roles—some wondrously subtle, others, when alcohol had eaten holes in his talent, embarrassing—I assemble a style of acting that may never have existed. And, being only in my memory, how can I express it?

When fragments are all you have, imagination must do the rest. In Bill Morrison’s movie Decasia (2002) he assembled pieces of severely degraded motion picture film into a long consideration—the term "meditation" is commonly used here, but I dislike the usage—on the beauty of loss. Fragments of silent film, slowly returning to the component elements of the nitrate film stock, unreel before our eyes to Michael Gordon’s haunting score. Figures flicker into solarized phantoms or are drowned in bubbles of decomposition. There are documentary scenes and those from dramas; actors, landscape and all is made equal in the face of decay. What is left is a glimpse, like a half-remembered past, or the eroding carving on a tombstone. The additional irony is that Decasia is available on DVD and Blu-Ray, which, like all digital storage methods, have limited shelf-lives. We commit our past to electronic storage for posterity when stone and paper last longer. Death reduces every reality to abstraction, washing away faces on film and names on stone without regard.

The two greatest paintings of burials in western art speak to these ideas from vastly different approaches. El Greco’s Burial of the Count of Orgaz, painted in 1586, is a monument; even its shape (vertical, with an arched top) suggests a tombstone. The headstone of the Orphan’s Friend is that shape. The painting illustrates a local legend: Gonzalo de Ruiz, a fourteenth-century Count of the town of Orgaz, was rewarded for his life of pious charity when Saints Stephen and Augustine descended from Heaven to take part in his funeral. They take center stage and cradle the dead man in their arms, while behind them is a living shroud of Spaniards in black, each face an icon of mourning. Above them the Count’s soul ascends into Heaven, to be received by Christ and the blessed. There is no setting; between Heaven and the mourners nothing can be seen to determine where this is taking place. All is about humanity living, dead and arisen.

What is El Greco showing us in these people? Everywhere there are faces, but most every gaze is turned inward. The mourners, carefully delineated, and modeled by the painter’s friends, are seemingly concealed by their thoughts. Even the Saints seem distracted at their task; Saint Stephen’s face is half-turned away from the corpse. Where eye contact is made it isn’t within the painting, but between it and us. A morose-looking boy, a torchbearer, stands in front of Saint Stephen, looking out, and gesturing to the Count. The Saint dwarfs him, making him seem preternaturally small, like some transplanted figure from a much older artwork; the precision of his pose emphasizes this. The sorrow in his face is more immediate than anything in the stylized, dance-like postures of the gentlemen in black. Perhaps the Count had a son, orphaned and out of place in this solemn setting? (There are no women in the painting save for the Virgin Mary in Heaven.) In the back, behind St. Stephen, a man peers out at us less blatantly. These two are thought to be portraits of El Greco himself and his son, Jorge Manuel. Overhead King Philip II of Spain sits in Heaven with the blessed, though he was very much alive at the time.

El Greco’s deliberate anachronisms, like filling the scene with people he knew from Toledo in contemporary garments, were a common conceit; an artist doing the same today would be called "postmodern." His splendid brushwork was never better: look at the highlights on the ruffs of the men in back, each a scribble of white dabbed with masterful surety. The nervous, living brushstrokes give movement to everything save the curiously rigid torch-flames. El Greco painted this for the Church of San Tomé in Toledo, where the painter was a parishioner, and where it still hangs in the Count of Orgaz’s funerary chapel. Immediately below the painting is a plaque with an inscription recounting the miracle. That it remains in situ is important; the entire chapel acts as its frame.

For centuries Christian religious art had one primary motive: to reassure. The oft-repeated scenes from the life of Christ sought to placate the fears of everyday living: He did this for us; He is watching over us. Pain is remote, though ever-present. The dead Christs are genteelly recumbent, their postures euphemisms or symbols. They are theatrical, and have that sense of disconnection that can come when things are seen from across a stage. Were artists not aware of this gap? In art as in most things we often avoid direct mention of death or pain, preferring the stylized substitute; I especially like the phrase "lost his life," as though it were only mislaid, and might yet turn up half-buried under papers on a desk, or in the back of a closet.

Art sometimes seems complicit in this whitewashing. Joseph Wright of Derby’s painting The Old Man and Death (c. 1773, collection of the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, Connecticut) must have packed a bigger punch in its day, but from our perspective it is genteel, even tame. The skeletal Death is picked out with a pre-Raphaelite fascination for detail, an unnatural clarity that today suggests computer-generated special effects. Though the skeleton is symbolic, that symbolism carried over the intensity of past generations and held a more forceful impact. I wonder if the deeper fears of the past were not more beneficial, considering the dangers to the world, which so many people today deny. Damien Hirst’s The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living (1991) circumvents the symbolism by presenting death in a clean, sanitized way. The shark in its tank does not address us, or anyone. It is a memorial commemorating death. No headstone, no life story, just numerous tiny pinpricks where the preservatives were injected into the carcass.

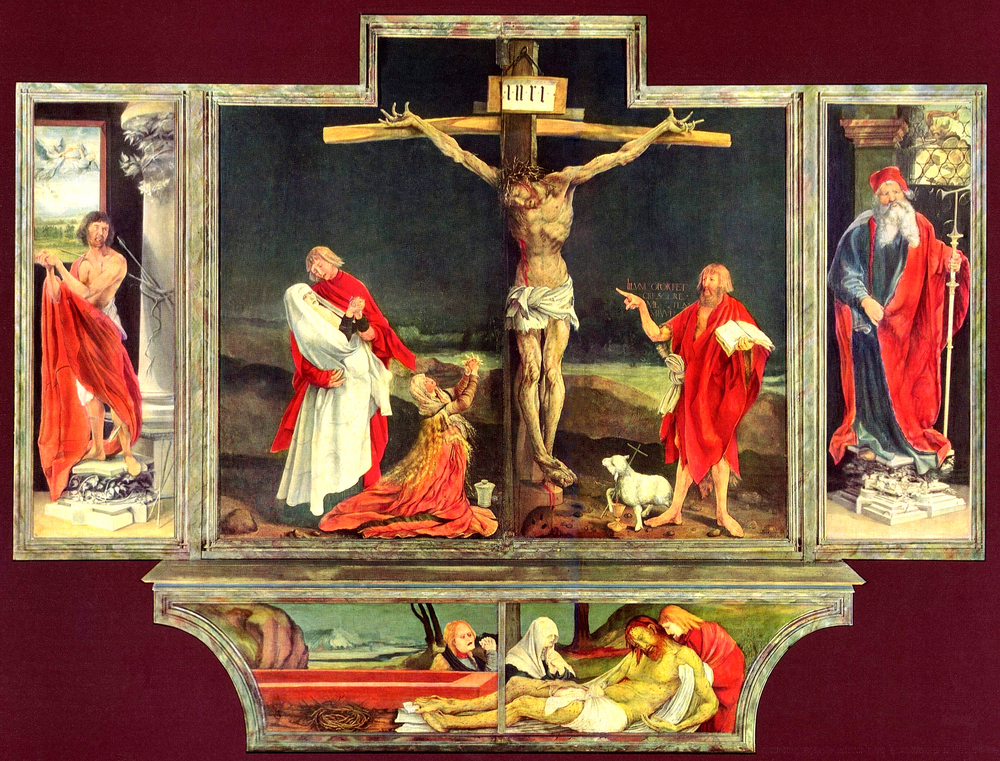

The exceptions, the blatant declarations of suffering, are few: Grünewald’s Isenheim Altarpiece (1512-16) at the Musée d’Unterlinden in Colmar, where Jesus’s body is contorted until it becomes an ideogram for agony, and especially Holbein’s Dead Christ (1521) at the Kunstmuseum in Basel, which captures the look of death as no other artist would for generations, perhaps until photography came to battlefields. The El Greco is firmly within the comforting precedents. Only the Count’s body, his mortal armor (itself wrapped in the armor of his knighthood) has died; his soul, eternally young, lives on.

"Death is not an artist," wrote Jules Renard, a sentiment I cannot digest. Is it that art has moved in to supply the missing element, thus potentially cleaning up and sanitizing what ought to be presented honestly? Which itself leads to the question: why present it honestly? Art is artifice, and many details can be left out or stylized to prevent their intruding on the focus of the work. The least romanticized deaths in art—from Grunewald and Holbein—are more about the spiritual ramifications found in each painting’s death than about the failure of the heartbeat and the myriad processes of decay. Is this why there is no great painting of the raising of Lazarus; because it is a scene in which death must be supremely present even as it is removed?

An important break with the consolatory tradition is Gustave Courbet’s Burial at Ornans from 1849-50, now in the Musee d’Orsay. How different everything looks, not quite everything. The shallow space of El Greco remains, thinly disguised with a landscape background. But what a scrim of a landscape—dun and desolate, though recognizable as the Chateau d’Ornans and the Roche du Mont, the view from the cemetery at Ornans. The very countryside appears in mourning, half-dead itself, draped in an inhospitable monochrome (partly the result of age) that helps limit perspective.

Courbet’s painting is a long horizontal that places the mourners in a rhythmic, expanded space. Too much room, perhaps. The right-hand side of the painting is almost all women, dressed in black, filing into the graveyard in a ragged, solemn procession. Again, this is drawn from life; by tradition men and women were kept separate at religious services. Most of the women are not even facing the grave. Like El Greco’s grandees, they are not looking at one another, but always inward, with faces half-obscured or turned away, which somehow makes their grief more genuine. The men on the far left are also obscured, in this case by their broad-brimmed black hats. For human interaction we are left with two: a tired young acolyte leaning against a man, his father, presumably, and looking up at him. The other is the crucifer, who, like El Greco’s torchbearer, is looking out at us. His knowing, almost sardonic expression heightens our sense of interaction; his long nose and dark hair make him resemble a refugee from El Greco’s Spain. All he needs is a ruff and a goatee.

A preparatory sketch for the painting from 1849, at the Musée de Besançon, offers a different motion. The grave is even less evident, as the funeral procession is passing by from right to left, as though the service had just ended. Two men stand by the grave, their faces slightly downcast. A few people appear to be holding handkerchiefs to their faces. The composition has no center, and less impact; it’s no wonder he focused the crowd’s motion on the grave.

This cemetery in Ornans was new. Napoleonic decrees were issued as early as 1804 ordering that cemeteries be moved beyond city limits [pdf], to put them out of church control and for hygienic reasons; cleanliness, in this case, was at a remove from godliness. Ornans, an unimportant town and hidebound by conservatism, delayed for more than thirty years before they opened their new cemetery, adjacent to land owned by Courbet’s family. Incongruously, Courbet shows a skull by the grave, as though the plot were being reused. A touch of memento mori, perhaps, or is it an attempt to re-emphasize the visual context? Again I think of Hamlet, and look for the comic gravediggers, but these stolid French faces hold no sign of humor, much less redemption or awe. We can only see how people are in a moment, self-contained yet sharing a common emotion.

The dichotomy is clear: El Greco’s expression of salvation after death, Courbet’s of the banality of loss. The missing element in Burial at Ornans—the corpse (probably Claude-Etienne Teste, Courbet’s great-uncle by marriage1)—becomes commanding by its absence. The event is more important than the man. Courbet’s painting is for Ornans and the world. In it we see the beginning of the counter-monument, where the act of commemoration is more important than the individual being honored; Monsieur Teste is merely symbolic in the context of his own burial, though the beadles and townsfolk show he was respected in his lifetime. The long horizontal format, based on the maximum size for history paintings at the Paris Salons, is part panorama, part dilution, spreading attention across the field, away from the grave.

Burial at Ornans is about one single moment, and beneath that moment the evanescence of memory and the fear that there is no hope save the hope we make ourselves. Realism with a capital R is a break with the life of the soul, except as it affects the transient. Courbet did not invent this; Rembrandt’s self-portraits, especially the late ones, show this contained moment with a certainty Courbet struggled to master. El Greco melded Byzantine mysticism and stylization with Titian and the Renaissance, creating a distinctly personal art, timely and eternal that transcended all influences. He was the John Barrymore of his day, interpreting familiar roles with his own peculiar panache. This is why, despite his fame, he was never successfully imitated; his art remained unique while changing the course of Spanish painting forever, laying a foundation for Picasso and Dalí. Few others spoke so strongly of the reach of life beyond the merely physical. Courbet stood alone, briefly; John Berger wrote of him, "He was the heroic St. Thomas of painting—in so far as he believed in nothing that he could not touch and judge with his hand."2 He cast himself as a near-caricature of the suffering, lonely artist. In fact, Courbet was widely followed. The Impressionists claimed him as one of their inspirations; photography both influenced and was influenced by him. The stress of this breakaway from academic tradition soured Courbet on success. Despite the acclaim that eventually came to him and Burial at Ornans, Courbet refused honors and finished his life in Swiss exile.

Courbet’s iconoclasm was a small step in the evolution of art, and not an unprecedented one. Brueghel and others found ample inspiration in the everyday; Dutch painting celebrated the secular life of the middle and lower classes as well as the gentry. But from Courbet comes the first groundswell that still occupies artists today. He made this challenge to the old hegemony the center of his later art, as contemporary artists devote their art to questions, not answers. In this sense art has become more spiritual, while shedding traditional religiosity, walking the middle ground between mysticism and the commonplace. The spiritual essence—call it the divine spark, as these are artworks concerned with religion—is an essential component of the artist’s approach as well as of the subject being portrayed. Finding that expressive element is the challenge. Some never do, though, according to the art-pantheism of Joseph Beuys, everyone has that potential. The search for that divinity needs a scientific term. Theometry, perhaps?

Painting was like theater, opera included: programmatic, frequently moralistic, and dependent on patronage. But painting was limited to statements, or did not posit questions effectively. Hamlet is all about questions and the attempt to resolve them. The Orphan’s Friend survives solely as questions through the accidents of Time. Through Courbet, into contemporary art, the range of values and nuance available has ballooned, encompassing answers, questions, and that catalytic middle ground, like a Zen koan. This multiplicity of possible viewpoints, and the validity of seemingly opposed viewpoints, is the challenge for contemporary artists. They must choose their answers and their questions with care, or risk producing glib art, art without soul. The divine spark became a burden, or perhaps it always was one.

Standing by those two enigmatic graves with the church at my back, there rises a long gentle hillside, forested up to the horizon. In Autumn the leaves turn red and gold and brown, a natural complement to the stained-glass windows; in Winter the gray branches clatter and sway in their own skeleton dance. At times, especially when the sky is a hodgepodge of clouds and sun, I would wish the graveyard were elsewhere, and leave this vista to open instead of closed eyes.

What use is a cemetery? Not a repository of memories; those belong to the survivors. If you have to go to a graveyard to remember someone, that person is better off dead. The grave is a private language. This is why memorials so often fall short; why Frederick Hart’s pedestrian statue stands beside Maya Lin’s modernism at the Vietnam memorial; why nothing built at Ground Zero in New York City would ever be adequate (and why anything built there will suffice, as memory fades with each generation).

Walking through the St Louis cemetery (#13) in New Orleans, so unlike New England graveyards in every respect, it’s hard to imagine this as a place of remembrance. It suggests instead an artist working in a small space. Really, what it suggested to me was Werner Herzog’s 1979 version of Nosferatu, though no such setting is to be found in the film. Wouldn’t Klaus Kinski, in makeup and cape, fit right in among the tightly packed mausoleums? The image of a cemetery as a place where bodies are returned to the earth is denied there, replaced with a more somber and fantastic atmosphere.

Some graveyards have grown beyond their purpose, into tourist attractions (Père Lachaise), or a national abstraction representing sacrifice (Arlington). This modern view of time—not merely conceding the impermanence of memory but openly surrendering to it—descends from Courbet and, at its worst, threatens to erase El Greco. But what an empty threat! Art is a benign form of narcissism. The awareness of our own humanity keeps us anchored in that middle ground. It’s no good looking for answers in stones; besides, who is there who really understands the questions?

- Matthias Grünewald, The Isenheim Altarpiece, Oil on Panel, 1512-16

- El Greco, The Burial of the Count of Orgaz, 1586-88

- Joseph Wright, The Old Man and Death, Oil on Canvas, 1774

- Gustave Corbet, A Burial at Ornans, Oil on Canvas, 1849-50

- Still from Bill Morrison’s Decasia.

[1] Mainzer, Claudette R. "Who is Buried at Ornans?" in Faunce, Sarah and Nochlin, Linda, eds., Courbet Reconsidered, Brooklyn Museum/Yale University Press, 1988 pgs. 77-82

[2] Berger, John, Success and Failure of Picasso, Penguin Books, 1965, p. 52

[3] There are three St. Louis cemeteries in New Orleans.