Six of the Ghanaian artist’s works are currently on view at the Mount Holyoke College Art Museum in a show called El Anatsui: New Worlds. Five of the pieces are mounted on the wall like tapestries. Some float just over the floor while others spill downwards. Gathered in some places and flat in others, the textures throw light in different ways to make the material read as swaths of velvet or sheets of glimmering gold coins. They appear weightless, suggesting movement through their dips and folds.

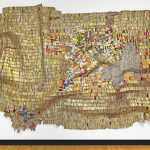

A prominent rectangular shape, intersecting lines, and a strong sense of design rule Alterego. More static than the rest, it lives outside the main gallery in a separate room filled with a bench and educational materials about the artist’s practice. It functions as an introduction to the show and a bridge from the traditional paintings and sculptures that comprise the museum’s permanent collection. But El Anastui’s commitment to the history of painting and representation carries through to the other works, evident in a sensitive use of color and pattern. Harbinger recalls the brush strokes of abstract expressionism through delineated swaths of color. Here, more so than in the other sculptures, the construction is obvious: scraps of metal are twisted together, patching a larger whole out of smaller parts. In each of the wall sculptures, sections of color fight against others, spilling out or swallowing each other up like the shifting territories on a colonial map.

El Anatsui, They Finally Broke the Pot of Wisdom, 2011, Found aluminum and copper wire.Mount Holyoke College Art Museum, South Hadley, Massachusetts Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York

El Anatsui, They Finally Broke the Pot of Wisdom, 2011, Found aluminum and copper wire.Mount Holyoke College Art Museum, South Hadley, Massachusetts Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New YorkThe wall pieces delicately balance design and materiality with the artist’s greater political points and They Finally Broke the Pot of Wisdom combines the two in a magical synthesis. It has two sections: The red and yellow center is rough, recalling burlap or other loosely woven cloth, while the space around it is a glittery sliver imbedded with symbols. Tension between the sections is palpable. The outside encircles the inside, but the inside pushes outwards and fights its own boundaries. Like a map that is in a constant state of flux over redrawn borders, it refuses to resolve, carrying a sense that it will change at any moment.

In the center of the gallery, the sixth, Tiled Flower Garden, translates the wall pieces into a literal topography. Sprawling from a central rock monument, the garden bucks against the edges of the gallery as if to imply it cannot be contained. Other parts spill into the center of the room and force viewers to skirt its edges, passing closer to the artworks than might be naturally comfortable. Navigating through the space in this manner becomes an embodied experience that argues for the wall pieces being sculptures instead of paintings or woven tapestries. To this end, the cast shadows expose the dips and bumps of their materials as they extend outward while light on the work’s surface shifts to reveal its dimension.

This physicality implicates the viewer as more than just a passive recipient of imagery. Just as one navigates unknown terrain with a heightened sense of where to place one’s feet, viewers must navigate through the constructed gallery space aware of their own bodies. The work dictates where we may walk. Its careful placement within the white walls creates artificial borders and boundaries that previously didn’t exist.

Each installation is different: El Anatsui asks curators to become involved in the creative process of display, becoming active participants in orchestrating the final gallery experience. The changing shapes of the sculptures foreground the artist’s practice as collaborative, mimicking his larger process where assistants are charged with construction. Production is a communal effort and the twists and folds of each aluminum piece stand as a testament to the human time involved.

El Anatsui, Tiled Flower Garden, 2012, Found aluminum and copper wire.Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York Photograph by Laura Shea

El Anatsui, Tiled Flower Garden, 2012, Found aluminum and copper wire.Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York Photograph by Laura SheaLikewise, viewers are implicated in the politics that his art describes. Instead of just sculpture or painting, it functions as a social practice meant to educate individuals. El Anatsui simultaneously draws on the traditions of his own culture and engages a globalized dialogue about art to bring the conversation to a wider audience. When viewers are engaged through the materials and forms, the artist can insert his dialogue regarding the politics of colonialism.

These politics are part of the larger conversation about the colonization of Africa, where European and American influence came in the form of the transatlantic slave trade. Europe, the Americas and Africa were engaged in a three-way triangle. Goods (including rum and other alcohol) were traded in Africa for slaves. These prisoners were carried across the Middle Passage to the Caribbean and sold for sugar to be carried north (to be distilled to rum). Today, the presence of alcohol in Africa is a direct link to its occupied past.

By using detritus that alludes to this history, the artist is in dialogue with a past riddled with slave trade and abuse. The cultural tensions that arise from colonialism express themselves in the sculptures through competing graphic shapes that are folded into and on top of each other. Sometimes, they are woven directly together. Each aluminum scrap is bound to another aluminum scrap. Flattened and twisted, their shapes and meanings have been transformed, but not erased.

They are on view at the Mount Holyoke College Museum of Art in South Hadley, Massachusetts through June 8. Their impact is particularly strong. They are installed at a time when we are interested in discussing equality and tolerance, and in this location: Massachusetts, a once colonized territory that historically has had little shame in colonizing others. Instead of offering solutions, the work is a chance to understand the struggles of colonial culture from the other side. It asks questions instead of giving answers. How do you read these pieces? How do you take this divided history and move forward, with respect and acknowledgment? And, how do we learn to be better?

- El Anatsui, New World Map, 2009, Found aluminum and copper wire. Private Collection. Courtesy of Jack Shainman Gallery, New York

- El Anatsui, They Finally Broke the Pot of Wisdom, 2011, Found aluminum and copper wire. Mount Holyoke College Art Museum, South Hadley, Massachusetts Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York

- El Anatsui, Tiled Flower Garden, 2012, Found aluminum and copper wire. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York Photograph by Laura Shea