By editors Lisa Crossman and Céline Browning

In the spirit of Black Mountain College, this text is written in a collaborative first person, thinking of Leap Before You Look through the lens of our own experiences as an art historian and practicing artist and educator. Our shared commitment to the arts, education, and writing led us to ponder how a show staged to teach us about the legacy of Black Mountain College—the mythical incubator of art and education experimentation—could give us new perspective on our own creative endeavors, and ultimately question: How should we “Leap Before [We] Look”?

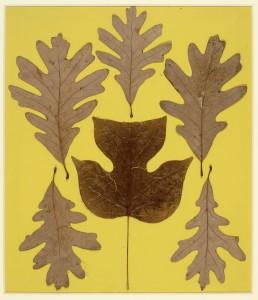

Josef Albers, "Leaf Study IX," c. 1940, leaves on paper, 28 x 24¾ inches. (c) The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation/ Artists Rights Society New York. Photo: Tim Nighswander/Imaging 4 Art.

Leap Before You Look, curated by Helen Molesworth with assistance by Ruth Erickson at the Institute of Contemporary Art/ Boston, spurs as much reflection about education as about the art that was created at Black Mountain College. The show offers keen insight into the many ways that the College influenced the pedagogy of liberal arts education and studio art programs in the United States, and how the legacy of the school has come to shape generations of artists’ works. As the show nears its close on January 24 before traveling to the Hammer, we have the opportunity to examine the programming that has unfolded since its opening on October 10, and to consider how the exhibition has donned the hat of, and made space for, both teacher and student.

On first viewing, the show strikes me as finely packaged post-mortem of a utopia; walking through the space, I have an eerie sense that an autopsy is being performed. The atmosphere is respectful, quiet, and the space is filled with a multitude of works that include autonomous art objects, material studies, photo documentation, and poetry. Looking at the many compelling works that line the walls and fill the cases, Black Mountain College seems firmly moored in the past.

The initial timeline signals the historical framework through which to view the curated objects. It informs us of the basics: Black Mountain College opened its doors in 1933–a year that marks both the closing of the Bauhaus in Germany and the introduction of the WPA in the United States (a federal initiative that put millions of Americans to work, including artists). The core philosophy of the school was rooted in the ideas of John Dewey (1859-1952)—US philosopher, educator and social reformer known for his call for a shift from authoritarian classrooms and rote memorization to student-centered models that supported a democratic learning environment.

Founded by the controversial classics professor and Dewey enthusiast John Andrew Rice, Black Mountain College was established as a liberal arts school that placed art making at the center of its curriculum and became recognized as an art school as time progressed and the list of reputable artist alumni grew. While Dewey’s philosophy was central and he even served on the Advisory Council, artists Josef and Anni Albers were the first visual art faculty hired at the College, and each played a major role in the school’s evolution until Josef’s resignation in 1949. Josef and Anni came to rural (and at that time conservative) North Carolina, seeking refuge from the Nazis and bringing with them their individual predilections for artistic training. Notably, they are presented as artists and teachers through the inclusion of their individual works as well as the inclusion of archival classroom photos.

An enlarged photograph of Josef Albers in the act of teaching is immediately visible upon entering the first gallery. This image, along with others interspersed throughout the exhibition, hold an architectural presence that bridges past and present, pointing to the significance of the archive as a rich source for reflection today. The photographs illustrate the day-to-day life at the College and contextualize the art making props such as the loom, piano, and dance floor, which read as both a reference to then and a portal to now.

A couple of iPads are casually included. I flip through the notes: “Color: related to design...dancing...piano / color...movement...tones.” The audioscape permeates the first few galleries; a selection of music ranging from Bach to jazz that was studied and performed by students, I learn from the wall text. Listening and looking merge as I ponder the cross-pollination of the arts at Black Mountain. Yet as I move through the galleries, it becomes clear that the show is loosely divided by disciplines such as music, dance, and poetry, as well as into broad organizing principles such as “Scarcity and Creativity”—grand ideas which shaped the evolution of the school. There is also a chronological component to the exhibition that charts the administrative shifts at the College.

Anni Albers and Alexander Reed,

"Neck Piece," c. 1940/1988, corks, bobby pins, and thread. Collection of Mary Emma Harris, New York. Courtesy the Jo

sef and Anni Albers Foundation. © The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo by Tim Nighswander/Imaging 4 Art.

When I first visited the show, the divisions seemed antithetical to the idea of a haptic educational environment that aimed to tear down artificial boundaries between fields. After repeated visits, however, they come to provide a useful organizing structure; while it’s true that the ceramic works are grouped in the final gallery, that the poetry lines the walls of that same space, and that the jewelry is together in one case, they are all contained within a single show, marked by their collective belonging. The students and teachers at the College were inspired by this interdisciplinarity: the undulating silhouettes in Susan Weil and Robert Rauschenberg’s cyanotypes are present in Ruth Asawa’s hanging sculpture, and the exuberant use of found objects is a resounding refrain that can be witnessed in John Cage’s (recreated) treated piano and Anni Albers’s and Alexander Reed’s Neckpiece made of corks and bobby pins.

In its finest moments, Leap Before You Look exposes the white walls of the gallery as a permeable membrane through which the ideas and creative energies of generations of students can flow alongside some of the finest artists of the last century. This directly reflects the College’s mutually supportive environment. While the administration of the school was faculty-led, its daily operations relied on the labor of both students and teachers working side by side. Art making was positioned as a necessary part of civic training. Further, the seeming emphasis on learning without a predetermined conclusion left space for experimentation and collaboration.

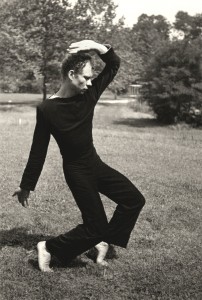

Hazel Larsen Archer, "Merce Cunningham Dancing," c. 1952-53, gelatin silver print, 8 ¾ x 5 7/8 inches. Estate of Hazel Larsen Archer and Black Mountain College Museum and Arts Center.

The student participation brings the legacy of Black Mountain College into focus and truly breathes life into this important show. Through a remarkably robust programming schedule and the invitation of nearby educational institutions to develop content, visitors are provided with a deeper experience of Black Mountain College as a site for active experimentation. The most notable examples are the Boston Conservatory dancers led by Silas Riener performing excerpts of Merce Cunningham’s work and students of MIT professor Kelly Nipper performing sets of actions developed as an extension of Theatre Piece No. 1 (collectively named Theatre Piece No. 1 x 50). Reinterpretation is an important part of the show; it is not about masterpieces, but rather about experiment, chance, and risk-taking.

The 20 x 20-foot dance floor and the piano, even unused, are legible as tools to be activated. They serve as props for staging the College’s scene and make possible the participation of contemporary artists. I sit on the gallery floor and watch students from the Boston Conservatory warm up, then Silas Riener dances Changeling in a red unitard and skullcap designed by Robert Rauschenberg, and finally the students dance. As I witness Cunningham’s reconstructed choreography performed,[1] I realize that this moment perfectly captures the interdisciplinary, collaborative, and horizontal drive of Black Mountain College as it brings together student and teacher collaborators across the divide of decades.

Dance and performance art are not the only examples of this innovative programming. The integration and use of art-making tools serves to highlight the importance of the haptic to Black Mountain College (an entire gallery is dedicated to the idea of haptic learning). Anni Albers’s loom from the College sits near the center of one gallery with a vibrant fiber work still attached. In the opening weeks, Sarah Peloquin, a Massachusetts College of Art and Design student, wove her work on the loom in the gallery, leaving it for the remainder of the show. This act is a perfect embodiment of the Black Mountain College way of life—namely, the acquisition of knowledge through direct experience—and it feels important that visitors are given the opportunity to see work not in a sealed case or behind glass, but in an ongoing state of becoming.

In Leap Before You Look, the creative process of learning and making is laid bare for contemplation. It exists in stark contrast to more polished shows that mask the pain and joy inherent in the creative process. In reperforming the work of the artists of yore, participants are working through history on their own terms: gaining ownership of it and trying to determine how to grapple with this legacy as contemporary makers and thinkers.

Museums, like schools and artists, are not finished masterpieces, but works in progress. As an institution, the ICA seems to be in a state of evolution too as it continues to define its role in the national and international contemporary art landscape. Director Jill Medvedow expressed this clearly when reflecting on the title of the show, which in her words "reflects the daring spirit of experimentation that defined BMC and that permeates the ICA today.”[2]

Leap Before You Look reminds us that the contemporary moment also is in transformation as we are constantly creating and considering our own legacy. This is a lesson that we, as educators, can take with us into the classroom: that perhaps the best thing we can do is to actively engage in this transformation with our students.

I stand near the dance floor, witnessing Björn Sparrman perform an hour-long action as part of Theatre Piece No. 1 x 50. He stacks and unstacks sets of handmade bowls arranged in a large circle—a mesmerizing repetitive action. Sparrman seems to measure time with his body, allowing the moment to unfold as he moves through a changing environment of his own making. I see his limbs shake slightly from the ongoing physical exertion as sweat beads on his forehead, and his eyes focus on the task in front of him. Straightening his back, he leaps...

------------------------------

Leap Before You Look is on view at The ICA Boston through January 24, 2015.

The traveling schedule for the show is as follows:

Hammer Museum, Los Angeles (February 21- May 15, 2016)

Wexner Center for the Arts in Columbus, Ohio (Sept. 17, 2016–Jan. 1, 2017)

------------------------------

[1] The performances of Changeling at the ICA mark the first time it has been seen since 1964 thanks to recovered video footage of the Cunningham’s solo.

[2] Jill Medvedow, “From Modern to Contemporary,” The Institute of Contemporary Art/ Boston, September 10, 2015, https://www.icaboston.org/articles/modern-contemporary.

- Björn Sparrman, “Theater Piece No.1×50.” ICA Boston, Dec.1, 2015.

- Josef Albers, “Leaf Study IX,” c. 1940, leaves on paper, 28 x 24¾ inches. (c) The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation/ Artists Rights Society New York. Photo: Tim Nighswander/Imaging 4 Art.

- Hazel Larsen Archer, “Merce Cunningham Dancing,” c. 1952-53, gelatin silver print, 8 ¾ x 5 7/8 inches. Estate of Hazel Larsen Archer and Black Mountain College Museum and Arts Center.

- Installation view, “Leap Before You Look: Black Mountain College 1933–1957,” Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston, 2015. Photo: Liza Voll Photography

- Installation view, “Leap Before You Look: Black Mountain College 1933–1957,” Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston, 2015. Photo: Liza Voll Photography

- Anni Albers and Alexander Reed, “Neck Piece,” c. 1940/1988, corks, bobby pins, and thread. Collection of Mary Emma Harris, New York. Courtesy the Jo sef and Anni Albers Foundation. © The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo by Tim Nighswander/Imaging 4 Art.