Thirty years ago prominent critics, historians, and artists testified in court on behalf of sculptor Richard Serra’s Tilted Arc, a seventy-three ton steel slab made for the Federal Plaza in Lower Manhattan. What Serra considered an opportunity for aesthetic challenge in a bustling public square, some of the space’s users saw as distasteful or threatening, and deaf to their needs. Public art is often contentious not only because it is placed in common spaces, making its aesthetic and conceptual value subject to the scrutiny of diverse audiences, but also because its cost, whether privately or publicly funded, is judged in terms of its success in serving the public. In 1989 Serra lost the case; the commissioning government agency removed Tilted Arc and Serra had it de-accessioned. Despite much dialogue about public art in the intervening decades, one might still wonder what movement there has been in the discussion and how art’s publics are accounted for today.

The MIT List Visual Arts Center’s annual Max Wasserman Forum investigated precisely this question over the course of a two-day program titled, “Public Art and the Commons.” From November 13-14, attendees viewed a new mural by Lawrence Weiner, toured MIT’s public art collection, and heard talks by Swiss artist Thomas Hirschhorn and practitioners in related fields. The List has been deeply invested in placing visual art within vernacular spaces, both in its installation of abstract sculpture on MIT’s campus and its pioneering student art-loan program. This conference presented a chance to investigate the broader stakes of such undertakings.

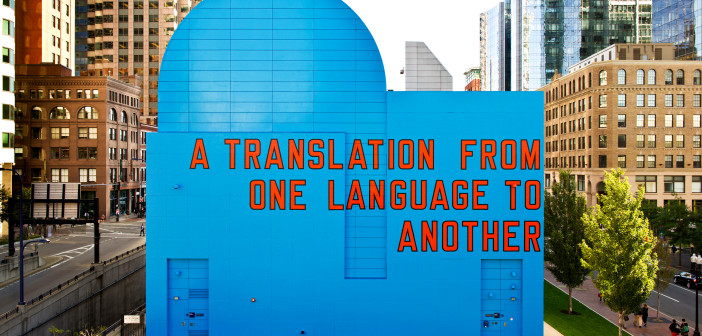

At the opening of Weiner’s mural in downtown Boston earlier this fall, Paul Ha, the Director of the List, stressed the importance of conceptual and abstract art in a city known for “men on horses.” Ha’s allusion to monumental sculpture deftly highlighted continuities between Boston’s revolutionary-era figurative sculpture and a new conceptual work of public art. Against an expansive blue wall, Weiner’s orange block lettering reads: A TRANSLATION FROM ONE LANGUAGE TO ANOTHER. Could this be the twenty-first century equivalent of “men on horses?” Weiner’s piece, located in the heart of Boston’s financial district, in the spot where Occupy Wall Street protesters first encamped four years ago, offers a notion of the monument that is playful and accessible but no less political. Thomas Hirschhorn, the keynote speaker at the List’s conference, spoke passionately about these competing demands.

In collaboration with the Dia Art Foundation, Hirschhorn organized the immersive Gramsci Monument from July to September 2013 in the Forest Houses community of the Bronx, New York. After researching and visiting many neighborhoods in New York City, Hirschhorn formed an alliance with Erik Farmer (President of the Forest Houses tenant association). Residents of the housing project built stages, a library, a radio station, a bar, and display cases for objects such as the slippers that the Marxist theoretician Antonio Gramsci (1891-1937) wore during his imprisonment by the Italian fascist government. After seventy-seven days of lectures and community-organized events, the monument was disassembled, leaving what Farmer described as a void.

Hirschhorn and the former Dia curator who assisted him, Yasmil Raymond, referred to the artist’s research on various housing projects as “fieldwork.” This struck a nerve for anyone familiar with the history of anthropological and ethnographic rhetoric, particularly because the fields were black communities and the person examining them a white European represented by the blue-chip Gladstone Gallery. The following day, New York-based Turkish artist Hakan Topal made the observation that it would not be feasible for a Turkish artist to undertake such a project in the Bronx, no less in Hirschhorn’s native Switzerland. Topal’s comment was especially apt in light of Hirschhorn’s labor practices that required residents to work relentlessly seven days a week, even using power tools in a rainstorm. Hirschhorn preempted such accusations by stating that he was interested in making art, not in helping the Forest Houses community; he wanted to know, he proclaimed, how the residents could help him. According to Erik Farmer, however, the crime rate decreased over the summer and many residents continued to find employment through the hiring agency Hirschhorn had used after the project ended. Hirschhorn’s rosy tone nevertheless raised questions from the audience about labor practices, costs, and funding.

After walking out of Hirschhorn’s talk, attendees learned that a series of fatal terrorist attacks had just occurred in Paris; the death toll rose throughout the night. When attendees returned to MIT the second day, public art felt secondary to public security. After a moment of silence, the day began, incidentally, with a discussion of the violence that broke out during the 2011 Egyptian Revolution in Tahrir Square and the 2013 protests in Gezi Park, Istanbul. The civic gathering spaces discussed were ones that concurrently allowed individuals to express dissenting views and abstracted them into mass ornament. It was helpful to have visited Weiner’s mural in Boston’s Dewey Square Park the day before, where, looking closely, one sees the prying eye of a surveillance camera camouflaged by paint. To visit this square is to become a figure on a monitor in some remote security office.

On this first panel, titled “The Square,” Hakan Topal shared his pseudo-archeological extraction of earth from the original sight of the Pergamon Altar in modern day Turkey, an ancient marble complex (think “gods on horses”) transported in the nineteenth century to a Berlin museum where it remains. He connected the illegal removal of valuables to neo-liberal regimes, the Occupy Wall Street movement, and demonstrations in Istanbul. Jasmina Metwaly and Philip Rizk discussed their film Out on the Street (2015), composed of semi-staged scenes among factory employees from working class neighborhoods in Cairo. After showing the film at venues in Berlin and Venice over the past year, they reflected on the way in which relocating political art from the public sphere to gallery settings defangs the work’s disruptive potential.

The second panel, “The Network,” critiqued the pretense to democracy within the online commons. If Twitter facilitated the Iranian protests and Facebook the Egyptian Revolution, then these can be read as valid democratic platforms, even if based on an idea of democracy imposed by western countries. Jodi Dean, Professor of Political Science at Hobart and William Smith Colleges, however, argued that the version of democracy these platforms offer is so closely modeled on capitalist formulations that it reveals democracy itself to be incapable of delivering on the liberal promises of equality and justice. Daniel van der Velden, co-founder of Metahaven – a design studio and think tank in Amsterdam, extended Dean’s critique, proposing that online platforms entrench their users in fictitious communities and do not actually afford access to political information. In this discussion, relational aesthetics became a straw man, as it was in all three panels, participatory in name yet powerless in impacting actual policy change.[i]

The final panel, on “The Institution,” was an open discussion featuring curator Bill Arning and artists Lina Viste Grønli and Lawrence Weiner, both of whom employ language as a sculptural material. Weiner suggested that all art is public as long as more than one person views it. He also explained that his art is not specific to a single site and can be installed in any number of places. Grønli spoke about shifts in opinion among communities over time; as people became accustomed to seeing a given artwork, they came to understand it as an integral feature of civic life.

The conference’s rich array of projects registered not quite a return to the conditions under which the Serra debacle unfolded, but rather reflected a neo-Cold War gloss of democracy, openness, and access. Many of the speakers suggested that these fallacies have found form in public art, embodied or virtual, in the post-9/11 era. The public is once more disingenuously watched over and art is called upon to provide circumscribed resistance to a culture of fear. The fact that an embedded surveillance camera in Weiner’s mural is seen as natural, as not warranting comment, demonstrates how thoroughly the “art” in public art has submitted to a precarious public.

The conference’s big reveal was an insinuation during the last panel that MIT’s public art program was initiated in the 1960s, in part, to assuage guilt for the institution’s complicity in World War II missile technologies. While abstract sculpture was also, of course, installed in public spaces to encourage creativity and sensitivity among the MIT community, the image of an Alexander Calder sculpture sweeping bombing victims under the rug is hard to shake. Dean and van der Velden scrutinized this internal contradiction in the online realm and others discussed attempts to find forms that could collapse the chasm between the art they make and the privatized public in which it is displayed. The takeaway from the conference, then, is that congruency between visual form and political commitment is highly elusive in public art. Gramsci Monument could not reconcile its pilgrimage visitors from Manhattan with its builders in the Bronx; Metwaly and Rizk do not want to show their film in art spaces; Weiner’s mural is spying on its own viewers. Through Weiner’s philosophical sophistication, one could not help hear a shred of halcyon naiveté in his concluding remark: “You make it accessible. Access is all you can do.”

[i] “Relational aesthetics” refers to event-oriented art of the 1990s by artists such as Rikrit Tiravanija and Liam Gillick. Nicolas Bourriaud developed the term for the exhibition Traffic (Bordeaux, 1996) and theorized it more fully in his 1998 text Esthétique Rélationnel, published in English as Relational Aesthetics (Dijon: Les Presses du Réel, 2002). Claire Bishop was one of Bourriaud’s early detractors. Jodi Dean cited Bishop in her remarks on the political impotency of this body of artwork. See Claire Bishop, “Antagonism and Relational Aesthetics,” October 110 (Fall 2004): 51-79.

- Pictured (left to right): Jordan Troeller (List Center), Thomas Hirschhorn (Artist) Photo: Judy West Photography

- Pictured (left to right): Gediminas Urbonas (MIT Program in Art, Culture and Technology), Jodi Dean (Hobart and William Smith Colleges), Daniel van der Velden (Metahaven, Amsterdam) Photo: Judy West Photography

- Pictured (left to right): Jordan Troeller (List Center), Thomas Hirschhorn (Artist), Yasmil Raymond (MoMA, New York), and Erik Farmer (Forest Houses Resident Association, New York) Photo: Judy West Photography

- Pictured (left to right): Henriette Huldisch (List Center), Philip Rizk (Filmmaker and Writer), Jasmina Metwaly (Artist and Filmmaker), Hakan Topal (Artist) Photo: Judy West Photography

- Lawrence Weiner, A TRANSLATION FROM ONE LANGUAGE TO ANOTHER, 2015 Photo: Geoff Hargadon

- Thomas Hirschhorn, Gramsci Monument, 2013 School Supplies Distribution by Forest Resident Association Forest Houses, Bronx, New York Courtesy Dia Art Foundation Photo: Romain Lopez