With Laurie Simmons’s new show at Salon 94 Bowery, she makes clear that conceptual photography has also been cornered and overwhelmed by a single, overbearing narrative. It seems that with every review of shows by members of the Pictures Generation—a loosely-knit group that includes artists as diverse as Simmons, Cindy Sherman, Richard Prince, James Casebere, Sarah Charlesworth, Louise Lawler, and Barbara Kruger—we get more of the same. With Simmons’s work, critics usually make vague references to gender, sexuality, domesticity, nostalgia, and the relationship between humans and objects. Very rarely are there efforts to cite her photographs within the trajectory of art history or to acknowledge them as photographs; Simmons’s images lose their material supports and become entirely transparent to social commentary—commentary that, it would seem, has not changed since the late 1970s. It is my hope that this process of interpretational neglect can be reversed for all members of the Pictures Generation in an effort to expand the analytical and aesthetic potential of their work. The time has come to go beyond the truisms of appropriation, media culture, and advertising, and dig deeper into how conceptual photographers actually engage with these topics through their chosen medium.

Kigurumi, Dollers, and How We See is exemplary of new avenues for discussing Pictures Generation artists. The show is an investigation not only of sexual and performance-based subcultures, but also of the interrelated politics of vision and the photographic image. Simmons’s recent interest in human-scale and humanoid figures, as I have argued elsewhere [pdf], is indicative of her sustained, evolving critical engagement with the medium of photography. This time, Simmons aims her camera paradoxically toward paint, and the two art historical monoliths of painting and photography must coexist within her theatrical space—whether they want to or not. In Brunette/Red Dress/Standing Corner (2014), for example, the figure, clad in blocks of industrial color and resembling a tube of paint, stands with one hand on each wall, as if acting as a strangely embodied bridge between disparate forces. Simmons thereby capitalizes on the corner’s indeterminacy and, as a result, expands the confines prescribed by histories of photography. Indeed, rather than acting as a commentator on or spectator of culture, Simmons actively manipulates crucial identity issues through complex, multimedia inquiries into the camera itself.

As early as 1982, Simmons began to consider the possibilities for a tentative coexistence with painting in her photography, an operation that also has implications for gender. In Red Bathroom (1982) from her Color Coordinated Interiors series, Simmons places Japanese "teenette" dolls in a geometrically dazzling bathroom oozing with bloodlike pigments, interrupted only by the rippling light of the camera’s flash and the impossibly white toilet and sink. The dolls are captured in a monochromatic hall of mirrors, in which walls and floors meet and diverge in unexpected ways, and foreground and background clash and repel each other. The artificiality of the scene becomes apparent, and the divide between the teenettes and their surroundings is made jarringly tactile. As a result of Simmons’s careful manipulation, the female figurines are simultaneously united by color, subsumed by it even, and excluded from the domestic interior that tradition mandates they should inhabit.

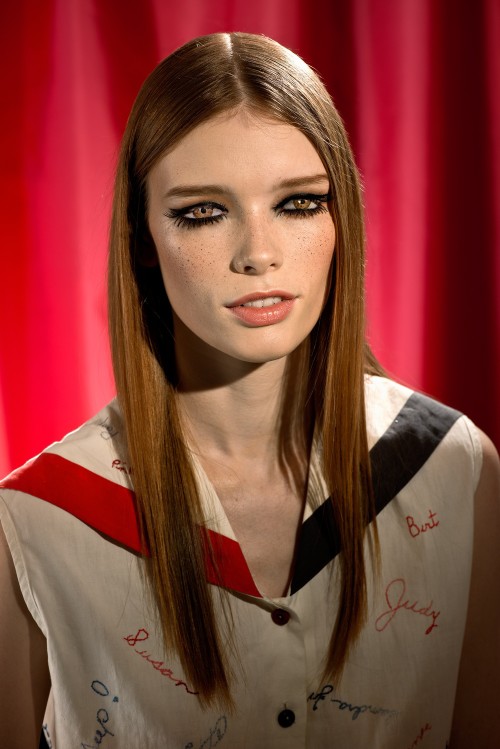

Laurie Simmons, The Love Doll/Day 22 (20 Pounds of Jewelry), 2010.

Laurie Simmons, The Love Doll/Day 22 (20 Pounds of Jewelry), 2010.Courtesy of the artist and Salon 94.

Simmons exhibits similar concerns in her 2009-2011 series The Love Doll, most emblematically in Day 22 (20 Pounds of Jewelry) (2010) in which a Japanese sex doll is in awe of the kaleidoscope of color draped on her body. Like an artist in the studio, the doll is faced with a profusion of pigments that are at once beautiful and terrifying. We fear that this poor figure, who has perhaps just discovered jewelry, might be strangled by the tentacles that envelop her. With the poorly drawn-on lipstick that covers her face, the doll becomes a canvas of sorts; her body becomes analogous to an interconnected web of color, pointing not only to the construction of a socially-regimented femininity through cosmetics, but also the history of gestural abstraction. It could be said that Simmons presents us with a photographic Jackson Pollock with none of the ejaculatory masculine bravado. She once again connects the medium with the body in an unexpected way that breaks down gendered and aesthetic expectations.

Enter an ingénue in a pink dress whose pasted-on smile belies the fear connoted by her body language. In Blonde/Pink Dress/Standing Corner (2014), something unknown is happening behind the mask that we cannot quite access; the camera registers the painterly, textured surface of the costume with such detail that we feel tantalizingly close to the space of the photograph. Still, we cannot help but wonder what is behind that surface, an urge Simmons capitalizes upon through the creation of a doubling shadow that serves to remind us of the unseen body of the actor. It is no mistake that, in 1859, Oliver Wendell Holmes likened photography to removing skin from an animal’s carcass. We would have no way of knowing the actual feelings, or gender, for that matter, of the actor. There is thus a tension between the act of costuming and the photograph. The former is meant to be a temporary performance, while the click of the camera fixes its subject for eternity in the same pose.

Further disrupting the scene is the presence of paint, not only on the figure itself, but also on the wall that frames the photograph. The small painted cars and inviting sun are so childish and amateurish as to look out of place. Even so, the paint appears to have the wisdom of many years of wear; it is discolored and cracked, begetting an unsettling combination of old and new, innocence and impurity. Occupying the corner carved out by these factors is the performer’s body. Paint and photograph are thus combined within the space of the body, tentatively uniting issues of gender and the medium within Simmons’s corners. Perhaps the two can work together in the common pursuit of transforming how we see.

The disrepair of the photographic/painterly landscape reaches a head in Brunette/Black Dress/Orange Room (2014), wherein the canvas of the scene has been punctured like Lucio Fontana’s slashed paintings. This is made more poignant by the combination of the figure’s sexualized pose with its decrepit surroundings. It is as if sexuality itself is decaying alongside the aging walls. There is a sense that something has been left unfinished or is being demolished, that both the identity of the actor and the room itself are in a state of flux. At the bottom of the photograph is a strip of painter’s tape reminiscent of that in Cindy Sherman’s makeshift studio from her 1976 series Bus Riders. Like a costume, the painter’s tape protects the space under it, and its removal reveals a blank strip unaltered by its adorned surroundings, creating an interspace between presence and absence. Like a Band-Aid on a wound, the painter’s tape reminds us of Simmons’s act of tearing open the space between photography and painting—media that have been traditionally kept apart or discussed as intrinsically separate practices. Both are engaged in a mutually constitutive process engendered by the camera.

This is not to say that Simmons is engaged in painterly photography. Instead, Simmons actively explores the confines placed upon Pictures Generation artists by multiplying the analytical possibilities available to the photograph. Her pictures are not solely about social commentary, as is often posited by analyses of photo-conceptualism. The sociopolitical conditions to which Simmons alludes are not separate from the photographs’ composition, reminding us that the camera is not only a recorder, but also the harbinger of ever-shifting and multifaceted modes of vision. One of the most unsettling pictures in the exhibition, How We See/Look 1/Julia (2014), presents yet another subgenre of costume play, in which fake eyes are painted onto the sitter’s closed eyelids. How We See/Look 1/Julia demonstrates how, in Simmons's work, vision is a process that is mediated by a variety of competing and complimentary modes of representation—painterly, photographic, and gendered. In this case, "natural" vision is coated with paint and transformed by the camera, whose truth function leads us to believe initially that her eyes are not, in fact, closed. There is something paradoxical about the startling detail the camera renders of Julia’s hair and the complete lie surrounding the very locus of vision: the eye. There is much more here than generalized allusions to gender roles, sexuality, or commodification—if we do not allow traditional accounts of the Pictures Generation to corner us.

In this way, Simmons’s corners are indicative of the impossible expectations that force women to exist in certain confines, as well as the confines that have been placed upon photographers tied together by generational similarities. What results from this combination is a medium-specific operation that works in tandem with the identities that Simmons has considered throughout her career. It is necessary to attend to the conceptual questions raised by Simmons’s work, but as with all Pictures Generation artists, it is essential to remember that there are questions of medium and materiality that require consideration as well. Privileging concept or medium is impossible in Simmons’s work, and we face their intersection in her constantly surprising visual and conceptual corners.

- Laurie Simmons, How We See/Look 1/Julia, (2014). Courtesy of the artist and Salon 94.

- Laurie Simmons, Red Bathroom, 1982. Courtesy of the artist and Salon 94.

- Laurie Simmons, Blonde/Pink Dress/Standing Corner, 2014. Courtesy of the artist and Salon 94.

- Laurie Simmons, Brunette/Red Dress/Standing Corner, 2014. Courtesy of the artist and Salon 94.

- Laurie Simmons, Brunette/Black Dress/Orange Room, 2014. Courtesy of the artist and Salon 94.

- Laurie Simmons, The Love Doll/Day 22 (20 Pounds of Jewelry), 2010. Courtesy of the artist and Salon 94.