The Whitney Biennial format has always tempted the guilty fascination of watching a train wreck. Any survey that attempts to take the pulse of a certain aesthetic moment in our current pluralistic mashup is bound to be a mess of good intentions jackknifed on the road to installation hell. This current survey presents no differently, but the decision to grant each curator a floor helps contain the damage so the viewer can engage in productive psychic triage in some of the intriguing cul-de-sacs created by individual artists and arts collectives.

Sterling Ruby, Basin Theology/Butterfly Wreck, 2013, Ceramic.

Sterling Ruby, Basin Theology/Butterfly Wreck, 2013, Ceramic.28 1/8 x 39 3/8 x 41 inches

Copyright Sterling Ruby

Photographer: Robert Wedemeyer

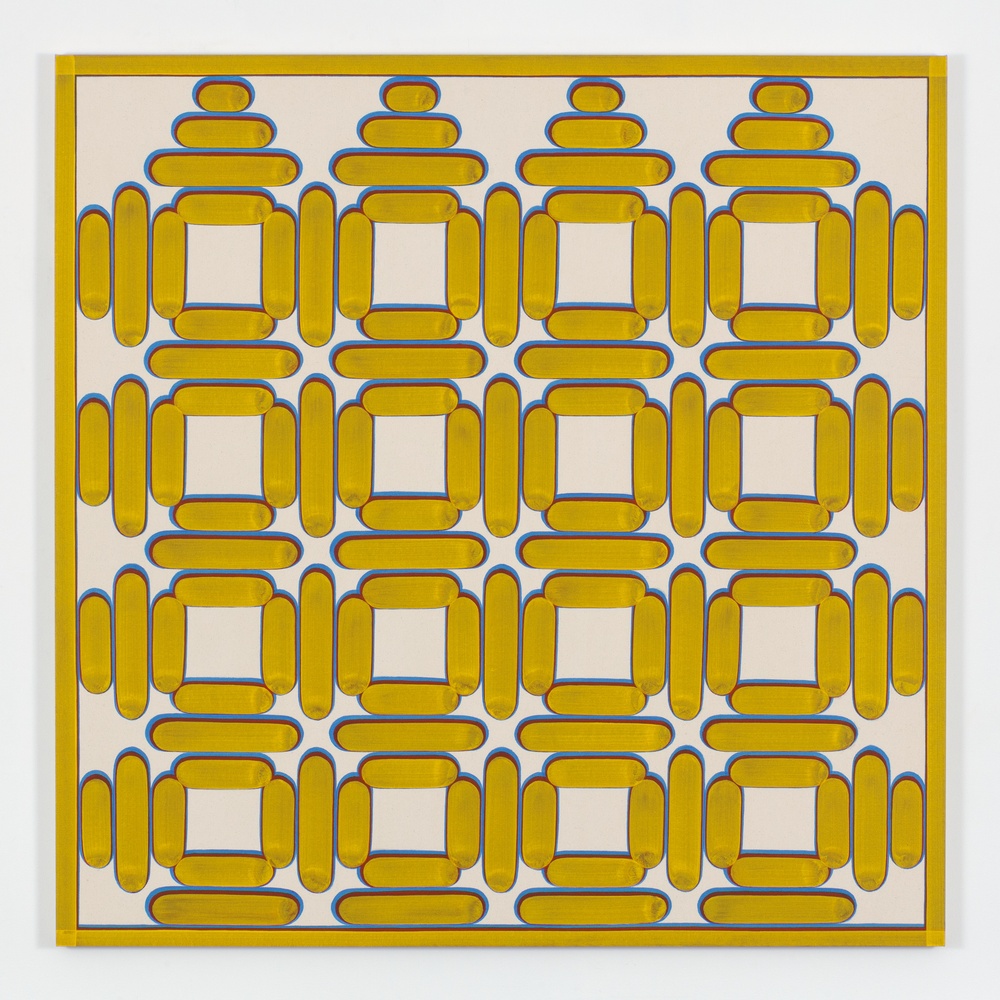

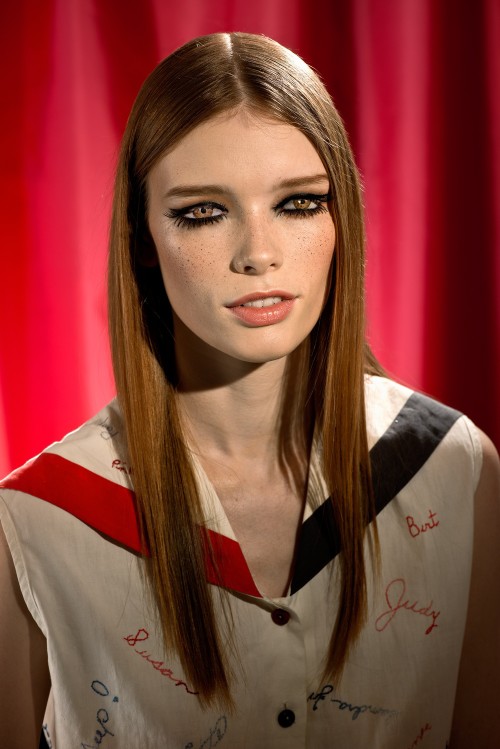

I began on the fourth floor, which Michele Grabner proposed to curate "as a curriculum for other artists." Her statement is a bold gauntlet thrown down to challenge the more typical curatorial mystique summoned on these occasions. In the floor guide Grabner goes on to say that "contours can be drawn around three overlapping priorities: contemporary abstract painting by women; materiality and affect theory; and art as strategy." One might argue the virtues of spelling out curatorial criteria so starkly, but one has to admire the force of focus in these goals. The collaged impact of Grabner's selection had an overriding crafts aesthetic to it. A wall-sized wave of woven videotape by the late Gretchen Bender, People in Pain (1988), dominates one section while three giant ceramic containers by Sterling Ruby, Basin Theologies (2013), squat nearby. A multicolored, floor to ceiling fiber work, Pillar of Inquiry/Supple Column (2013-14) by Sheila Hicks, dominates another section of the floor. The sense of touch was called forth but at a somewhat canny distance. This dissonance between tactile form and shrewdly worked out theoretical content was the dominant feel of Grabner's floor. Dona Nelson's painted and woven, two-sided works, juxtaposed with Amy Sillman's abstract paintings in collaboration with the sculptor and ceramicist Pam Lins combined the pictorial with the tactile in shotgun marriage. Amidst all the action I was drawn to the strong poetry of Louise Fishman's two gestural abstractions, and wished that more of this type of individualized approach to painting's historical influence was on display.

Descending to the third floor, I first encountered a wall of Ken Okiishi's gesture/data (2013), over-painted flat screen monitors with what seemed to be collaged commercial video playing underneath. It's amazing how transgressive the simple idea of painting a screen can still feel today. Apparently the painted parts were inspired by an encounter with Joan Mitchell's works. Okiishi was selected by Stuart Comer, as was the rest of the third floor, which was markedly different than the fourth in its heavy integration of film and video. The most stunning presentation here (and perhaps in the entire Biennial) has to be Leviathan (2012), a remarkable film by Lucien Castaing-Taylor, Véréna Paravel and Harvard University's Sensory Ethnography Lab. Shot from multiple point of view with an array of GoPro video cameras in high definition, the film opens a small but epic window on a commercial fishing vessel, its catch and its crew. One incredible shot tracks a severed fish head as it rocks back and forth, in extreme close-up, into the camera's eye before being washed out of the fishing ship's waste scupper. In another shot the camera dips below the roiling ocean surface revealing a slew of mauled by-catch, popping up rhythmically to track a squadron of hungry gulls descending from the sky. This is an epochal masterpiece, combining issues of environmental degradation with visceral images of both unforgiving man and unknowable nature. Since Comer comes from a background in time-based media these choices are apt, and tend to give his selection a more contemporaneous speed of acceleration than Grabner's floor. But Comer also includes some artist installations that require a slower pace to assimilate and reward the viewer in less spectacular ways. I found this balance between the studied and the spectacular tactically brilliant. Julie Ault's section, for example is so humble as to almost disappear among all the other visual stimuli on hand.

Amy Sillman, Mother, 2013-14, Oil on canvas.

Amy Sillman, Mother, 2013-14, Oil on canvas.91 x 84 in.

Collection of the artist; courtesy Sikkema Jenkins Co., New York. Photograph by John Berens.

Her installation Afterlife: a constellation (2014) included a copy of the New Yorker featuring an article on Sylvia Plath and Ted Hughes, an antique photographic stereo view documenting the Donner Party of the Sierra Nevada, works of "outsider artists" hand reproduced by the photographer and filmmaker James Benning, and graphic and sculptural works by David Wojnarowicz and Robert Kinmont. Ault's "show within a show" grew out of her abiding commitment to collaborative research and innovative combinations and presentations of social and aesthetic issues, the kind she helped pioneer in her involvement in multiple groundbreaking Group Material installations and actions. The 2014 edition of the Biennial could almost represent homage to Ault and her strategic retooling of contemporary curatorial criteria. After all, the very same tactics of interpretive relationships and pedagogical opportunities first worked out on a grand scale by Group Material pervades the overall show. Another installation along these lines was presented by Triple Canopy, a literary and arts collective based in Brooklyn. Their Pointing Machines (2014) assembled what looks like a museum conservation alcove of fragments of American colonial and early republic artifacts. An antique washbasin stand is shown in three different iterations, the original and two 3-D modeled versions. While the group's stated intent here is to set up a dialectic between the mechanical reproducibility of artifacts and their dissemination as yet another form of cultural information, they could take a few cues from Ault in terms of steering clear of too didactic a presentation of that intent.

Anthony Elms curated the second floor. A number of his choices include individuals who are not professional artists per se, that is they don't fall into the easily identifiable categories of painting, sculpture, film or even performance. Gary Indiana is a prime example. Primarily known as a writer of fiction and essays, rather than a maker of aesthetic objects, Indiana presents an odd conceptual video, Stanley Park (2013), in which he conflates a panopticon prison on the Isla de la Juventud in Cuba, Presidio Modelo, with a rise in jellyfish proliferation on the northeast coast of Canada. The piece doesn't ever really integrate into a cohesive statement of a critique of minority incarceration rates and environmental emergencies, despite its high-tech fabrication. A different but more satisfying conceptual stretch could be found in the late Terry Adkin's piece Avarium Series (2014). Multiple aluminum rods extended overhead from a large wall, skewering an array of disk cymbals and trumpet mutes, and evoking bird calls' sound waves. This was a loud piece that spoke in silence, and put a more sharply conceptual spin on a craft aesthetic. Elms also chose Zoe Leonard to reconfigure one of the museum's unique windows into a camera obscura, projecting a "live feed" of Madison Avenue upside down on an opposing wall. While always a cool thing to encounter, this seemed like rather thin gruel for the artist, who is best known for her photos gritty streetscapes and sewn orange peel sculptures. Joseph Grigely had a fascinating room in which he created his own "show within a show" of documents culled from the lost archives of the critic and writer Gregory Battcock. Grigely apparently stumbled upon this cache of documents while roaming around an abandoned storage facility in his studio building. Laid out here, it offers a fascinating slice of art and life in New York in the late '60s and '70s, including Battcock's involvement in underground gay culture of the time. Battcock was a rebel when it came to the art world at the time. While he wrote an important early book on Minimalism and was well respected among his peers, he seems to have chafed at the rigid categorical distinctions in the arts at the time, and so seems an apt avatar for this Biennial and its will toward categorical creep.

There are of course many more fascinating and strong artists and works in the overall show that I can't fit here, along with many less interesting presentations. One promising trend reprised from the 2012 Biennial was an expanded schedule of performance, discussions and screenings, most, but not all, happening on the museum premises. These opportunities to be present in heightened social participation help to emancipate the contemporary art spectator from mere tourist status. On the whole the 2014 Biennial ends on an optimistic note in that it ramps up categorical confusion while offering that very confusion as a possible model. Rather than look for a grand unifying zeitgeist, the show seems to say, let's become more comfortable with living with contradiction, and the more babble the better, if it means even temporarily escaping a monotonous normative narrative.