"Boston Common" highlights the people and organizations that shape Boston and New England's cultural sector by going straight to the source to find out who they are, what they are doing, and how and why they do it. We hope that the interview series will champion some of the exemplary work being done, shed light on neglected issues facing our arts scene and community, build connections among individuals and organizations, and expand the networks on which we rely. In our newest installment, we talk to Boston Cyberarts Director and independent curator George Fifield.

How did Boston Cyberarts get started—did you see a need in the Boston community that wasn’t being met?

I started curating in the early 90’s, and among other things, I curated an exhibition called The Computer is Not Sorry. It was the first computer installation show in Boston. One of the things that came out of that was that I was asked to write a column for Art New England about art and technology, and I wrote that for many years. One of the things I learned writing was that this area was an epicenter of art and technology for the rest of the country—all these things were going on, but no one in the art world knew about it. If in the late 90’s you asked someone what contribution Boston had made toward art, contemporary art, they would have said expressionist painting. And so my idea was to celebrate this somehow. Which gave me the idea for the Cyberarts festival. Right from the beginning, there were two basic organizing concepts to the festival; that it would foster collaboration between organizations, and that the work displayed would be in all media.

How did the all media component of the festival come about?

Because there were so many people interested in being a part of the festival who were in different media, and because by that time I had realized that when you talk about digital media, there’s really only one media, and that’s the zeros and ones. From there you can output as sculpture, as music, as whatever you want. You can input from almost any media—it’s all really part of the same thing. To give you an idea about the festival, I thought the first one (in 1999) would be a success if 20 organizations participated, and 60 ended up participating—this was clearly a conversation whose time had come. Our initial appeal to funders was twofold: one was cultural tourism and the other was to portray one of the state’s economic engines in a very positive light, as a creative activity.

Mark Skwarek Occupation Forces, Augmented Reality work displayed on the Rose Kennedy Greenway as part of the 2011 Boston Cyberarts Festival

Why did the festival end in 2011?

The reason for the festival was to get art institutions in the area and artgoing public comfortable with new media, and they were. By 2011, everyone was kind of into it, it sort of became clear that we won so we were ready to declare victory and go home. It’s not like we weren’t going to be providing lots of other examples of this kind of work—at Atlantic Wharf in 2011 we had dance and technology throughout the year, we had electronic music throughout the year. We’re still doing that to some degree at Boston Cyberarts. And we’ve got these big public art projects on the Marquee and the Harbor Island Welcome Center.

How did you became a curator?

During my 20’s and 30’s I was working as an artist, and I was always an artist with a foot in technology. My first serious art form was color xerox. At that time I co-owned a business called Plastic Image and we had the finest color Xerox machine on the east coast, and we sold high-end color Xeroxes to artists and architects and engineers. After that I got really involved in video art. It was at a time when all the video art programs collapsed, and I really wanted to see video art and so I said “how about I start a video art evening.” In time I discovered two things: I’m better at curating than I am at making my own work, and curating is an art form. It was about this time that the deCordova came to me and said “we want to show video art and we can’t find anyone in town who knows how to show it, will you do it?” And so I became a curator and never looked back. I started as the curator of video art at the deCordova, and as my interests changed, my title changed to curator of new media. In 2005 I left the deCordova, and I’ve been an independent curator ever since.

What would your advice be to someone who realizes that their studio practice is not as successful as their ability to evaluate, bring together and write about the work of others?

I’m not sure I would suggest that anyone do what I did. It sort of happened almost accidentally to me. But I would suggest that they go get a degree in art history or curating—there are many programs out there. Having said that, I think the difference between being a practicing artist and being a practicing curator is that to be a good artist you have to somehow have blinders on; you don’t want to be completely open to everything you see, but to be a good curator you have to look at everything. And as you look at more and more work, patterns start to form. So what I advise young curators to do is studio visits and look online and join organizations and go to conferences, and really look at a whole bunch of work. To look at the whole landscape and see patterns.

How has the Boston art scene changed in the last few decades, and how has the place of digital art changed during that time?

Boston has always had a very strong artist’s community and a very strong local gallery community, which you don’t always see in other cities. Part of the thing that supports the art community is the colleges and universities. In terms of the digital aspect of the question—when I started the festival, there were some major digital artists who lived in Boston and had shows all over the world, but no one in Boston knew who they were. I’ll give you an example: Karl Sims, at the time had had shown at the Pompidou in Paris, had won a MacArthur genius grant, but no one had seen his work in Boston. And so for the very first festival, Nick Capasso curated a group show at the deCordova of people we thought were very important digital artists and we put Karl in it, and it was just mindblowing to everybody. So I think one of the things that the festival can take credit for is elevating the profile of these artists and elevating the City of Boston to its rightful position as one of the major cities for digital art in the country.

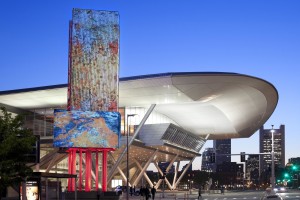

François de Costerd & Todd Antonellis Axiom #3: Territory, Work displayed as part of "Art on the Marquee" at the Boston Convention & Exhibition Center

What do you think the defining characteristics of digital art are?

It’s a very broad field, and it gets broader every day. At the end of the day (and you can argue with this, I can argue with myself about this until I fall asleep) it’s about the code. Somewhere in there is digital code, and that is manipulated somehow, and comes out as a drawing, as an interactive installation, as a piece of literature, as an app. The reason the field is expanding is because all of these things that even 10 years ago cost outrageous amounts of money to get your hands on, you can now go out and buy—some devices you don’t even have to learn how to program. Oil paints aren’t becoming cheaper by a power of ten every five years.

Do you think digital art is more democratic than other art forms?

Well, at its best, I think you have to bring a certain technical ability to the creation of digital art. The really good digital artists know how to code—that keeps the democracy out of it. I mean, Photoshop made for a lot of bad artwork—democracy has a lot to answer for. But the good stuff happens when you really know how to get in there and manipulate it yourself.

Can you name one of the recent events or programs you’ve had at Boston Cyberarts that’s been particularly successful?

The first show we did this year was one that looked back at the 20-year history of Otto Piene as the Director of the Center for Advanced Visual Studies. This was successful party because the work that came out of the CAVS was all over the world, and it was all created here. At the closing ceremony of the 1972 Munich Olympics, this giant balloon rainbow that Otto Piene invented went over the entire Munich river and stadium, and it helped everybody come to terms with the tragedy at that Olympics—it was an amazing work of art. The very first one of those actually went over the Charles river. One of the things I always tried to do with the festival and I still try and do today is keep reminding everybody about the history of digital art in Boston. But there’s all these areas that still, people don’t know about, like app art. Jodi Zellen put on a show in L.A. that was mostly iPad art, which we brought to the gallery. We had 4 iPads with art on each one.

Can you name a few of your favorite works in the genre of app art?

I’ll give you the place to go: iphoneart.org. It’s curated by an Austrian artist named Lia, and it’s got all the really good art apps in it. John Baldessari made one in conjunction with LACMA, some of my other favorites are by Scott Snibbe, he’s got a few, one by Andreas Muller called For All Seasons, then also Lia’s Philia 01.

Looking beyond Boston Cyberarts to the Boston art community at large: can you name a recent event in the area that has exceeded your expectations?

I would say the efforts at the MFA to bring performance art into their programming. If you had told me 10 years ago that the MFA was going to be one of the preeminent organizations showing performance art, I would have laughed. Also the openness of the ICA during the last festival (in 2011) to host a show on augmented reality. The group ManifestAR came and put augmented reality works in the lobby and around the building, they also gave talks and showed people how to use their phones to access the work in augmented reality. There’s actually one work that was done for the show that’s still there. It was done by my friend Tamiko Thiel and it’s one of the few pieces that can be seen all over the world, but she created it for the ICA. It’s called Jasmine Rain (Birdcage).

What are some issues that the Boston art scene still has, and are there any changes you hope to see in the future?

I think the Boston art scene is doing pretty well—it’s vibrant, there’s a lot of activity, there are galleries that run the gamut from highly commercial to slightly crazy… it’s very healthy. In many ways, the big problem that Boston’s always had is that there’s no funding source for independent, non-profit galleries. If you’re in your studio making work, and you can’t take that work and show it to somebody in a public space, then there’s something missing—and that’s what Boston needs more of.

- Boston Cyberarts Gallery Otto Piene & Electronic Art in New England Photo Credit: James Manning

- Mark Skwarek Occupation Forces Augmented Reality work displayed on the Rose Kennedy Greenway as part of the 2011 Boston Cyberarts Festival Augmented Reality exhibit on the Greenway during the 2011 Boston Cyberarts Festival

- François de Costerd & Todd Antonellis Axiom #3: Territory Work displayed as part of “Art on the Marquee” at the Boston Convention & Exhibition Center