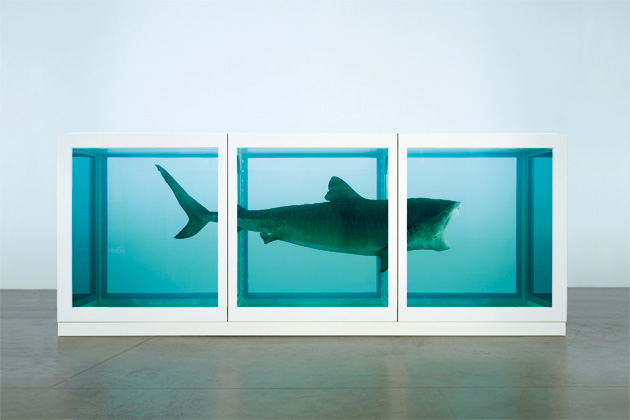

Damien Hirst’s most famous artwork, The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living (1991), better known as "the shark," spent 3-years on loan to the Metropolitan Museum in New York from the Steven and Alexandra Cohen Collection, which acquired it in 2004. The Met made no special effort to highlight this new visitor. To the contrary: they installed it in a modest gallery in their 20th Century wing (the Lila Acheson Wallace Galleries), and at first supplemented it with a handful of paintings arranged vaguely around the theme of the sublime. What other museum could be so ho-hum about a major loan? What’s one more masterpiece at the Met?

The surrounding works were inconsequential; when I first saw the installation, few people looked at the paintings or read the wall text. A children’s group entered the gallery, and the kids spun in orbits around the tank, pointing and staring. For adults the shark is also the cynosure; only a Francis Bacon, included as an example of anti-sublime, had a chance of drawing attention. It was too small and poorly placed to have much effect.

Bacon, with his work’s unrelenting hopelessness and twisted physiognomy (a sort of biomorphic cubism) might make an interesting, discordant counterpart to Hirst. For all the implied pain of a real dead animal, whole or flayed or sawn in pieces, Bacon’s paintings carry a much more visceral charge. Seeing Hirst’s preserved and not-so-preserved animals is to explore the idea of death and pain, at a safe distance; to see Bacon is to come uncomfortably close to experiencing them. Close, but not identical; for the most part Bacon observes without being drawn in. His expressionism often ends at the background; with a few exceptions (primarily his paintings after Goya) his people suffer in flat clinical environments.

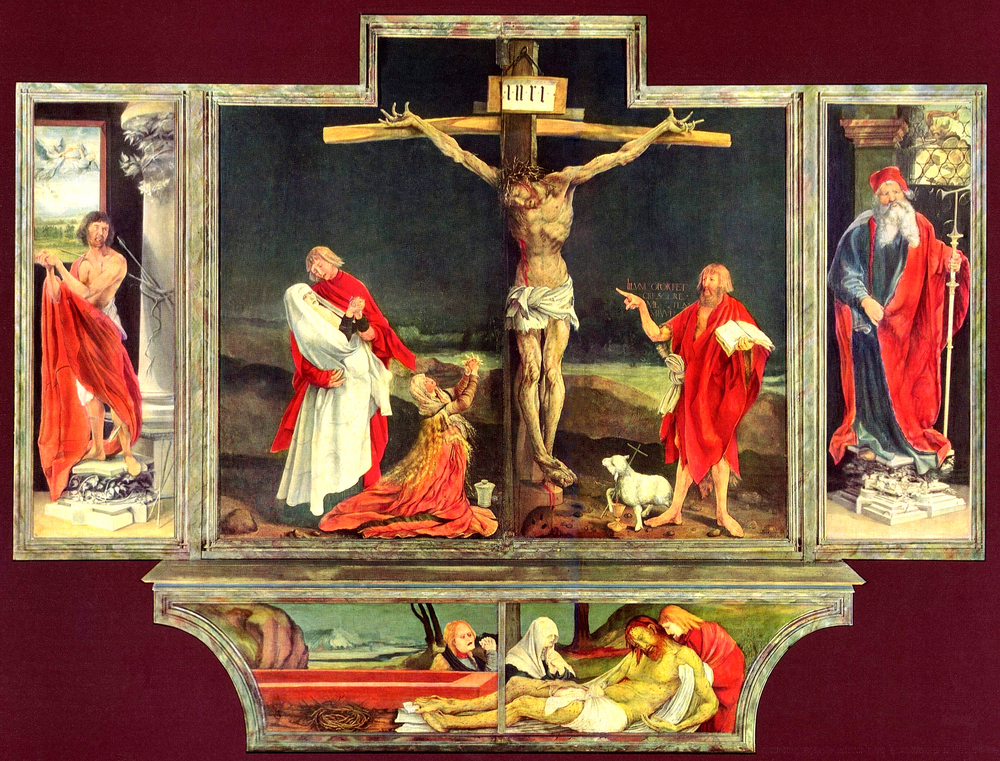

Pairing the shark with a roomful of Bacons would be ill-advised and potentially traumatic. Other works, unrelated thematically, might fill the bill. The Clyfford Still paintings in the adjoining gallery, with their brilliant reds, might clash and contrast with the cool aqua blue of the shark tank. Some of the Met’s religious works could tempt—martyrdoms of various kinds—but their specificity reinforces the shark’s anonymity and the randomness of death. A subsequent installation, Anish Kapoor’s Yet to be Titled (2007), was much more appealing; there’s no thematic link, just two eye-catching works of art keeping company together.

Conceptual art allows for variation: for example, the end result of Lawrence Weiner’s One Standard Air Force Dye Marker Thrown into the Sea (1968) is dependent upon ocean currents and the weather. I don’t have to explain the work, do I? The title says it all. Hirst had to replace his original shark, which was imperfectly preserved, with a new one. The original, a 14-foot long tiger shark, decayed from within until the owner at that time, Charles Saatchi, had it skinned and the skin stretched over a frame. In keeping with conceptual principles, all three (shark, framed skin and new shark) should be considered the same work. And so they are. The differences are mostly subtle and natural, but Hirst made one significant choice: the original shark had its mouth slightly open, a grimace comical or menacing and a little unnatural. The replacement shark has been suspended in its tank with its mouth wide open. Is it crying out, or about to bite? (The teeth are not as intimidating as I expected.) It’s best not to anthropomorphize. Hirst will insist on putting his animals into explicitly human actions—a grim version of a Disney cartoon—which undermines their impact. Puncturing a dead bullock a la Saint Sebastian (Hirst’s Saint Sebastian, Excruciating Pain, 2007) has only slightly more gravitas than dogs playing poker. The harmonic convergence of Hirst’s desire to humanize the inhuman must be his Mickey (2012), as Mickey Mouse is already a surrogate human, doubly disguised in unconvincing mouse ears and Hirst’s dot painting style, always capering in human ways. Try to imagine Mickey Mouse peeping out of a hole in the wall and scampering for a bit of cheese. Hirst’s Mickey exists solely because the Walt Disney company commissioned it, to be sold to benefit a charity—good works in keeping with Mickey’s character.

Without a story to sweep The Impossibility . . . along, details leap out. The shark is punctured with many tiny pinpricks, assumedly where the preservatives were injected,1 and not another St. Sebastian reference. Needle tracks are evocative, but not as much on a shark’s skin than on a human’s. The open mouth, the unseeing eyes (it does not seem to look at you, no matter where you stand) give character to what is just a lot of formaldehyde-marinated meat and cartilage. Because there is no story being told, nothing is altered by a new shark.

The shark says nothing of itself. Art has stripped down meaning, through Malevich and Mondrian through countless abstract artists, who celebrated the object, to the Conceptualists, who often removed the object. The shark suggests without telling, or without telling much, not even alluding, as in, say, a Cindy Sherman photograph. It is an actor backstage, in makeup yet not in character, aloof from plot and performance. This makes it unique in Hirst’s oeuvre, and places it above the rest. Overstated works such as the St. Sebastian, and works entirely without affect—such as his spot paintings—have littered Hirst’s career ever since. These are so poker-faced and post-Warholian (Warhol, among other things, having removed narrative from realist imagery until it came close to abstraction) that when Gagosian gallery showed the "complete" spot paintings through its eleven branches in 2012, only 300 of the then approximately 1,400 dot paintings were actually shown. There was no need to be completist, despite the title, for there was nothing lost in the works not shown, most of which would have been executed by Hirst’s assistants anyway.

Sharks suggest their own history, of anger and violence. "Jaws" just perpetuated the stereotype. Walking on—I made sure to see the shark every time I was in the Met—I moved to the overwhelming calm of the Dutch masters, their soothing, homey browns and golds were a welcome change. Perhaps ruddy-cheeked cavaliers, laughing at the face of aggression, their stomachs showing under their gleaming breastplates, would have made boon companions to the shark—merry company to lighten the gloom. Kapoor’s multipart mirror shows us ourselves, blurred and almost pixellated, begging for the "selfie." I don’t know how this shark was killed—there are two punctures under the dorsal fin—but, as the title says, death is not understood. Art is more abstract than war; a dead shark is more abstract than death. The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living is a great work, worth the company of the Met’s many masterworks. Too bad it wasn’t there permanently.

Hirst’s second most famous work, For the Love of God, is a skull cast in platinum, based on an eighteenth-century skull Hirst bought in Islington, and studded with 8,601 diamonds, weighing 1,106.18 carats. It is a vanitas for the bling age, a memento money. Would it have succeeded with lesser materials? A plastic skull, aluminum instead of platinum, cubic zirconia instead of diamonds? If the answer is no, then the materials matter more than the meaning. Decorated skulls are for anthropological exhibitions, with skin long turned to leather and cowrie-shell eyes, or Day of the Dead celebrations; Hirst spoke of a turquoise skull at the British Museum as an inspiration. And the meaning itself is one drawn from long ago. Would another gemstone do? Either way, there is something very heavy metal (as in music) in the work—glitz and morbidity being blood brothers in the headbanging world. Hirst himself wore a jacket with a silver skull on the back to the skull’s debut at London’s White Cube gallery. To present it properly requires careful lighting — limelight, perhaps? For impact, Subdoh Gupta’s Very Hungry God (2006) a huge skull made of stainless steel pots and kitchen utensils (at the Palazzo Grassi, Venice) makes a more substantial and substantive impression.

The vanitas was a standard subject in painting, an embodied contradiction. The message of eschewing earthly goods was a perfect subject for the artist to display skill in painting those very goods, and the result would lend an air of piety to the tapestried, gilded and bejeweled homes of the wealthy. Hirst’s butterfly pieces evoke stained-glass windows but without a message, unless you like the wholesale death of butterflies.

Hirst’s famous shark is a witty and spectacular take on the memento mori, but it’s a one-shot idea. The more explicit the religious imagery, the more shallow the work as a whole appears. This is not an age to shout your faith from the rooftops—ballyhoo is for televangelists. Perhaps the embrace of Mammon is what Hirst is pointing to, but he does so clumsily. This reliquary for the common man does not speak of a life that was lived (only the teeth hint at reality), which might be Hirst’s point. When Hirst is quiet, his message is better heard and more resonant. Leave the heavy-handed symbolism to the late Thomas Kinkade, a religious artist at the opposite end of several spectra. Kinkade’s factory approach (only reproductions sold, no originals) has queasy echoes in Hirst’s broad range of work. That’s not a compliment.2

When I think about the now-infamous skull (owned by a private group that includes Hirst) I wonder about the soul who came to this strange end. Hirst said he wanted the skull to be flawless, but what does flawlessness have to do with humanity or, for that matter, death? At least the platinum skull sports the real teeth extracted from its model; they, in their imperfection, remind us of a life that was lived. The shark and, to a much lesser extent, the skull, suggest what we cannot accept, and what our minds cannot encompass. Hirst’s saving grace may be what his art proves: the he, like us, might have the odd good idea, but beyond that he hasn’t got a clue. Recent news that Hirst, who is writing a memoir, cannot remember the 1990s at all, only adds a little grim humor.

Hirst’s nearest counterpart is Jeff Koons, which is not entirely a compliment to either artist, though Koons comes out the worse. Both men can produce artistic candy—beautiful things without real substance—and both can straddle the line between profound and vacuous; yet neither has produced more than a handful of works up to their potential. Koons is the holy fool, earnest in speech but steeped to nausea in consumerism; Hirst the cheeky yob with dreams of sanctity, at least some of the time. It’s easy to dismiss Koons: Beneath his message is the shallow water of pop culture. For Hirst at his best, beyond the glitz there is death. Perhaps in a few decades—when both are dead—we will be able to put both men in perspective. Hirst’s art sometimes deals with death and God, but the surrounding media frenzy is more circus than church, though the implication that to miss his exhibits is somehow sinful has died away. We have gotten used to him.

Much of my bafflement regarding Jeff Koons is the adulation that has surrounded his work. He took the Warholian irony that has been a steady tributary in the river of art for decades and made it into the center of his work. Instead of mass-produced printing methods such as Warhol used on his paintings, Koons uses the finer craft of porcelain and such, but it’s the same thing conceptually, just gilded and enervated. Like Hirst, Koons employs some very fine artisans. His work is always glossy and elegant, in its way. But he took Warhol’s influence and took it beyond its logical conclusion, until there is little other reaction possible than to just be sick of it. It cloys. Jules Renard, a century before either Hirst or Koons, wrote in his Journal, "Irony does not dry up the grass. It just burns off the weeds."3 An interesting sentiment, though I think that Koons has proven that a weed, when left unchecked, chokes itself out of existence yet does not stop growing. Post-Warholian irony is dead and Jeff Koons is one of the assassins. Damien Hirst can build an expensive container to put the ashes in, lest we forget.

- Damien Hirst; The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living; Glass, painted steel, silicone, monofilament, shark, and formaldehyde solution; 1991. Photographed by Prudence Cuming Associates © Damien Hirst and Science Ltd. All rights reserved, DACS 2012

- Damien Hirst, Mickey, Household gloss on canvas, 2012. Photographed by Prudence Cuming Associates © Damien Hirst and Science Ltd. All rights reserved, DACS 2014

- Damien Hirst; Saint Sebastian, Exquisite Pain; Glass, painted stainless steel, silicone, arrows, crossbow bolts, stainless steel cable and clamps, stainless steel carabiner, bullock, and formaldehyde solution; 2007

[1] When Carol Vogel viewed the shark for The New York Times as it was being treated (Oct 1, 2006), she was told the needle marks would not show.

[2] Roberta Smith also compared Hirst to Kinkade: see "After the Roar of the Crowd, a Damien Hirst Auction Post-Mortem," The New York Times, September 19, 2008

[3] Renard, Jules, Journal, December 26, 1899