It is important to note that I am first speaking to a context, then to a condition, and finally to an example or test case. In late 2012, Richard Kalina wrote an article in response to a questionnaire sent out by The Brooklyn Rail’s guest ARTseen editor Irving Sandler on the state of art criticism in which he stated that Painting today is a "continent" onto itself in the world of art, and the universe of visual and cultural studies. As he wrote, "while other media . . . ostensibly offer more opportunity for overt innovation, painting has now essentially marked off its overall set of boundaries and is engaged in the task of elaboration and infilling. There is much work to be done in painting, but something has changed. Painting has ripened, altering our sense of expected innovation. While new things will happen in painting, that ‘newness’ will be of a different order."3 He continues on to say that, "[p]ainting by its nature tends toward conditions of material separation from the world. It resists (but does not preclude) the interactive and the interdisciplinary—an important part of our culture today and something that other media deal with more naturally. It has remained largely a matter of a certain specific material, paint, applied to flat rectilinear surfaces coincident with a vertical wall."4 One might question is this advantageous or detrimental? As his argument progresses he articulates that painting’s long-standing preeminence in the visual arts nudges (or rather encourages) painters today to recognize that "painting is generally more engaged with (and bound by) the history and development of [their]own medium than are [practitioners of]other forms of art",5 this coexisting in an ever more "a historical environment" leads to a heightened recognition and analysis of Painting’s history by its producers.

In an equally erudite and hilarious essay entitled "Art Was a Proper Name" in his book Kant After Duchamp Thierry de Duve narrates an imaginary time in the future when an alien explorer happens upon the remains of our civilization on earth and is quickly presented with the challenge of defining this thing we called "art" to his superiors. Through a variety of investigative, art historical and archaeological methods the scout is once and again dumbfounded and unable to define the essence of this "thing", and can only ultimately point to the model of Duchamp’s Fountain. The extraterrestrial finds that "This particular urinal has nothing in common with any of the countless things carrying the name of art, except that it is, like them, called art. And nothing distinguishes it from just any ordinary urinal, from non-art, except, once again, its name, art."6 The difficulty to understand a specific tradition, craft or discipline in our cultural production proved to difficult to dwell on, so it moved on to investigate the idea of art. Is it just a waste of time to spend so much time wrestling with minutiae that does not ultimately have any effect on the end product? Is something more or less art when you consider its productions, authenticity or authorship? Of course, we have been through this—over and over. If there is anything freeing in this time of the "post-critical"7 let it be that we are exempt from asking the same questions ad nauseam. But, then again how do we tackle this question of the continent of painting, which I am quite certain not one amongst us will deny exists today?

The somewhat provocative title of this brief essay points to a critical issue/problem in contemporary art in general; and moreover, the sub-discipline of Painting. I am speaking of the resuscitated corpse of Modernism, or Neo-Modernism, the moniker some have recently and aptly given this condition. My title also refers to both the slightest kernel of a progressive concept and the execution by the contemporary artist and its (big air quotes) "critical" reception. This ailment, whether you refer to it as "Provisional Painting" like Raphael Rubinstein8 or as defined by the cohort of painters dubbed "the New Casualists"9 by Sharon Butler, is a condition we can safely say has infected contemporary painting like the ebola virus.

Barry Schwabsky described this current style of painting, which he notes was prevalently on display at the Frieze Art Fair in New York this last spring "retromodernism" in The Nation. In his words, "This, call the style retromodernism, [is]a term meant to be oxymoronic. At a purely descriptive level, retromodernism would mean a synthesis between figuration and abstraction (mostly geometrical rather than gestural) in a manner that evokes the spiritual and intellectual strivings of classic modernism, but elides—some might say, betrays—a modernist faith in progress, replacing it with nostalgia." This observation intersects the oft-quoted statement by Karl Marx, in its original context: "Hegel remarks somewhere that all great, world-historical facts and personages occur, as it were, twice. He has forgotten to add: the first time as tragedy, the second as farce."10 If we were to extend this line of thought, which I think Schwabsky is, we would then begin to question the motives for flogging the dead horse of modernism forsaking the avant-garde and its progressive moves to re-shape society. But, why now has this "look" of modernism resurfaced? Recently, David Geers spoke to this, in his words, "nostalgic retrenchment" in an essay titled "Neo-Modern" published in the journal OCTOBER in early 2012, "It is, in equal parts, a generational fatigue with theory; a growing split between hand-made artistic production and social practice; and a legitimate and thrifty attempt to ‘keep it real’ in the face of an ever-expansive image culture and the slick ‘commodity art’ of Koons, Murakami and others."11

Yves-Alain Bois, I believe, prophesies this very issue in his essay "Painting: The Task of Mourning"12 wherein he describes the set of conditions that allow painting to cyclically play out its death in a Sisyphean manner; or as it was dubbed by Douglas Fogle, "the Lazarus effect".13 We have simply inversed the endgame. We are no longer formally working ourselves towards the end of painting as an object but focusing more and more of late on the strategies of painting as evidenced in the work of Rudolf Stingel, Josh Smith, Peter Acheson, Alex Hubbard, Michael Krebber, and countless others (though to be fair in disparate ways). If Painting can only speak to its failure or its limits, what is it worth? And why are so many of our current discussions about Painting increasingly focused on abstraction? Could it be because mostly, and let me emphasize not exclusively, abstraction today seems to be about "Painting" as narrowly defined by modernism? Is it because, like Krebber, they primarily deal with only the project of Painting, this reduced understanding of the discipline, not what it is capable of today? All of which brings us back to this consideration of the concept of retromodernism.

At this time, I would like to direct our attention to Wade Guyton, whose retrospective exhibition at The Whitney in late 2012 received a great deal of editorial attention. In one of the rare reviews of this exhibition that did not just recycle the museum’s press release Barry Schwabsky commented, "He is one of those artists who makes paintings but never paints, and his eschewal of anything recognizable as a traditional act of painting is precisely what redeems him in the eyes of those who believe that painting is prima facie reactionary, and acceptable as contemporary art only when it somehow or other isn’t painting."14 He goes on to declare that ". . . his painting isn’t painting because it’s printing. Every commentator on his paintings has explained the process by which they are made."15 I must add that most of the other, for the lack of a better word, "reviews", focus an inordinate amount of time explaining in excruciating detail the process by which his paintings are made along with equal doses of a personal narrative of the artist. None seem to focus on what these paintings speak to, or address his regurgitation of the look of small-m modernism. Which leads us to easily accept the notion that the work is not made in relation, or contrast to its predecessor, but rather that it more likely is simply complicit in an omnipresent industrial art-fair complex where the look of criticality in Painting has come to stand in for any type of forward momentum or opposition.

But, if you study the countless essays penned about his work in the past several years, to question this work publicly labels you a philistine, or maybe just a simpleton. For example, Jerry Saltz writing in New York Magazine quoted Loren Munk16 who stated that many are " ‘fatootsed’ because Guyton creates with a printer; painters are ‘annoyed’ that Guyton is ‘trying to eliminate’ the hand. These folks let ideology get in the way of the retinal payoff of this work, and it’s too bad."17 Saltz continues to state that "[Guyton] pushes the technology beyond its means, overloading it until the optic field fluctuates, and afterimages appear that reverberate with tensions that belie the apparent casualness of the process. It’s like seeing a mechanical aurora borealis. Guyton’s is a sort of quantum touch: There and not there at the same time. It exists between the artist’s computer screen and the way his printer handles its invisible transmission of pure information." This is all part of what I think was brilliantly phrased as the "ambiguous terrain" of contemporary art by Geers because as he elicits ". . . such a project18 represents a cynical model for a contemporary practice that now searches for loopholes and blindspots in a constant hedging of bets. In effect, it allows the artist and the collector to have it both ways-the luxury of aesthetic pleasure and its simultaneous disavowel."19 I would go further and state that the manner of production Guyton employs in his work is not what is threatening, rather it is its emptiness.

In his review of the Whitney exhibition, Saltz goes on to comment on what he sees as the "hypersensitivity" evident in Guyton’s work to the critical theories of the seventies and eighties by saying, "It’s as if he’s covering the classic rock of Modernism, Minimalism, and Post-Minimalism, reenacting the tried and true." He continues to state that these ideas "feel more imposed than discovered, less intellectually acrobatic than his process. This quasi-nostalgia provides Guyton’s work a troubling, lurking aura, implying a double-edged Romantic wish that art can again be what it was." Could it be that in part this nostalgia is symptomatic of a condition wherein the lack of, or our distance from, an overarching agency for painting has brought on a sort of melancholy or mania as suggested by Yves-Alain Bois?23 In writing about Guyton’s work, Scott Rothkopf, the curator of The Whitney exhibition states, "We’re late not just to modernism’s party but to postmodernism’s too."24 As I stated before this could be seen as a freedom, but moreover its viewed in this more defeatist manner. Once again in Rothkopf’s words, "it is not so much saying there’s no such thing as an original image, but knowing full well that it’s not a very original thing to say."

In a much discussed article published in The New York Times entitled "How to Live Without Irony",25 Christy Wampole, an assistant professor of French at Princeton University tackled what she considers the "ethos of our age":26 irony, and how it functions in society and collides with concepts of nostalgia and authenticity. Her thesis builds in part on how the "ironic frame" functions as a "shield", as an example she speaks about an ad that pokes fun at its own format while calling attention to its self-awareness as an ad, tempting to "lure its target market to laugh at and with it. [By doing so] . . . it pre-emptively acknowledges its own failure to accomplish anything meaningful."27 In this fashion, it walls itself off from attack, with a wink-wink and a nudge-nudge. It is in this light that I make the comparison between Krebber and Guyton, both respectively working from opposite ends of a false-truth or definition of Art via Painting. Is playing the "game"28 on a meta-level a similar type of shield? Furthermore, I want to ask if when considering Guyton’s work are we really speaking to the object or the project? And, I suppose it is worth asking if today the two can be uncoupled?

Another attempt to define this condition of "the contemporary",29 as it has been called by David Joselit in his recent work, may be part of the problem with the current discourse surrounding and isolating Painting. In addressing the "vast image population explosion" facing us today in his recent text After Art, Joselit concludes that the proliferation of visual data in our age lead to the breakdown of the modernist "era of art". It is no longer necessary to argue for the autonomy of art, nor is it possible for anyone now to maintain that visual art alone has the capacity to produce alternative realities in our connected and endlessly networked age of the screen. Instead, he addresses a different type of agency, ". . .‘art’, defined as a private creative pursuit leading to significant and profitable discoveries of how images may carry new content has given way to the formatting and reformatting of existing content—to an Epistemology of Search." He continues on to state "the major consequence of this shift is that art now exists as a fold, or disruption, or event within a population of images".30 This is counter to the match, set and game modernity played out on an endless loop.31

I would argue that it is in this fold, this interstice, where Painting may now find its home. Not necessarily in opposition to the screen but rather in relation to it, more of a symbiotic relationship. In representational terms, Painting as a window functions differently, it is a disturbance, a passageway that is also a storage bin of time, information and experience. It is a space between, a filter, and an activity that is inherently about temporal expansion and accumulation. Today we may fully understand that we reference a reality that is already an image (a thing that it is nomadic, able to rapidly change scale, location and context; something never fixed in any given material form). But within this context, Painting could be the locus to fix the image, and a method to engage the other in a physical form that is both familiar and alien—a new twist on its agency of yore.

The issue we face is not whether we are hopelessly doomed to continually resurrect Modern Painting by mining the muck of history in an attempt to glean overlooked gems or processes, or one where we feel the need to wall off the discipline in order to protect its pedigree. These types of maudlin pursuits are neither necessary nor beneficial to the tradition of Painting; rather they are corrosive. The question facing Painting now is how it can exist in our current landscape of big data, without it being distilled into extinction in a distributed network where images are readily "collected" via smartphone as opposed to being engaged physically.32 The struggle we are facing is for Painting to be seen, demanding to be looked at without the filter of the screen coming between the object and its interlocutor. What we need to identify is a method of engagement that goes beyond simply addressing Painting’s auratic nature. Certainly, this is a difficult issue to sort out (and not one where I claim to have the solution), but to re-engage in this exchange is better than sticking our heads in the sand while the dialogue about Painting is simply set on repeat.

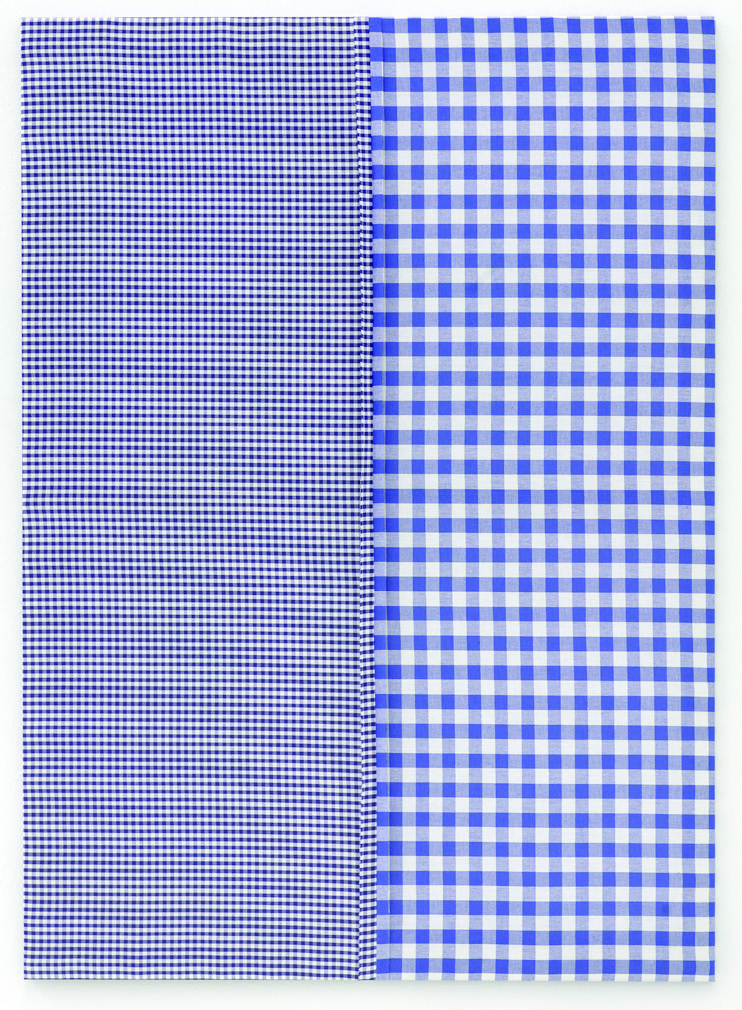

- Michael Krebber, Untitled, Fabric on canvas, 120 x 90 cm, 2006. Courtesy of dépendance, Brussels

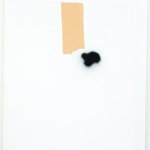

- Michael Krebber, Funny Cide 2, Charcoal and lacquer on canvas, 180 x 150 cm, 2011. Courtesy of Maureen Paley, London

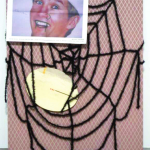

- Michael Krebber, The Things We Are Doing No. 1 (Reiher Sonne), Fabric oval-shaped canvas in yarn spider web on fabric, paper, 120 x 100 cm, 2003 Collection Martin & Rebecca Eisenberg

- Exhibition views Michael Krebber: The ridiculized snails 11/15/2012 – 2/10/2013 – CAPC musée d’art contemporain de Bordeaux Photos: Frédéric Deval (pictured left to right) Untitled, 2004; Untitled, 2002; Untitled, 1993; Untitled (14), 2007; Ich habe nie Begleitung. Ich habe Magenprobleme, 2003; Tiga, 2008; Untitled (30), 2007; Fanatic Hot Rabbit, 2011.

- Installation View: Wade Guyton 11/15/2007 – 12/15/2007 – Petzel Gallery, New York Courtesy of the artist and Petzel, New York

- Wade Guyton, Untitled, Epson UltraChrome inkjet on linen, 84 x 69 Inches, 2007. WG 07/078 Courtesy of the artist and Petzel, New York

[1] In 2007, I organized a panel with Lance Winn of the University of Delaware on the subject of contemporary painting. One of the panelists, Barry Schwabsky, was working out a set of ideas and questions that became part of an essay entitled "Object or Project? A Critic’s Reflections on the Ontology of Painting" found in the text Contemporary Painting in Context ed. by Anne Ring Petersen with Mikkel Bogh, Hans Dam Christensen, Peter Nørgaard Larsen. Museum Tusculanum Press - ISBN978-87-635-2597-8. This session in its entirety, but in particular this presentation, lead us to reconvene another panel titled "Reframing Painting: A Call for a New Critical Dialogue" at the 101st Annual Conference of the College Art Association held in New York, NY in February 2013. This prior discussion inspired us to look more deeply into the subject; moreover, it lead to a desire to investigate and contemplate the entropic nature of the critical discourse of Painting that still intrigues me to this day.

[2] A term used with obvious allusions to a seminal essay by Thierry de Duve, "When Form Has Become Attitude - And Beyond" (1994), which was republished in Theory in Contemporary Art since 1985, ed. by Zoya Kocur and Simon Leung, Blackwell Publishing, 2005. ISBN - 0-631-22867-5.

[3] From "The Four Corners of Painting", published in The Brooklyn Rail, Dec 2012-January 2013. Online at brooklynrail.org

[4] ibid.

[5] ibid.

[6] Kant After Duchamp, by Theirry de Duve, MIT Press and OCTOBER - ISBN 0-262-04151-0; p.13

[7] To allude to Hal Foster’s eponymous essay first published in OCTOBER, vol. 139, Winter 2012

[8] Raphael Rubinstein, "Provisional Painting", Art in America, May 2009

[9] Sharon Butler, "Abstract Painting: The New Casualists", The Brooklyn Rail, June 2011; and in "The Casualist Tendency", Christie’s Magazine, January/February 2014 and online at Two Coats of Paint.

[10] Karl Marx, "The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte", First Published in Die Revolution, 1852, New York, NY

[11] David Geers, "Neo-Modern", OCTOBER, vol. 139, Winter 2012

[12] Yves-Alain Bois, Painting as Model, MIT Press and OCTOBER Books, 1993. ISBN 978-0262521802

[13] Douglas Fogle, "The Trouble with Painting" from Painting at the Edge of the World, Walker Art Center, 2001. ISBN 0-935640-67-3

[14] Barry Schwabsky, "Generation X", The Nation, December 3, 2012

[15] ibid.

[16] Saltz notes that in this case Munk was writing under the pseudonym "James Kalm"

[17] Jerry Saltz, "On Wade Guyton’s Brave New Inkjet-Printer Paintbrush", New York Magazine, October 29, 2012

[18] I must note that in this specific context he was not speaking directly to this artist, but rather Josh Smith. He goes on to extend this critique to others though he never mentions Wade Guyton.

[19] David Geers, "Neo-Modern", OCTOBER, vol. 139, Winter 2012

[20] Insofar as it is discussed by Barry Schwabsky in print quoting an essay by John Kelsey in the essay "Object or Project: A Critic’s Reflections on the Ontology of Painting", from the text Contemporary Painting in Context ed. by Anne Ring Petersen with Mikkel Bogh, Hans Dam Christensen, Peter Nørgaard Larsen. Museum Tusculanum Press - ISBN978-87-635-2597-8

[21] From "Stop Painting Painting", an essay from "Man Without Qualities: The Art of Michael Krebber" in Artforum International, vol XLIV, no. 2, 2005.

[22] ibid.

[23] Referencing "Painting: The Task of Mourning" by Yves-Alain Bois in the text, Painting as Model, MIT Press and OCTOBER Books, 1993. ISBN 978-0262521802

[24] As quoted by Daniel Birnbaum in "Pictures Eating Pictures: Notes for Wade Guyton" from Parkett, vol 83, 2008, in reference to the essay by Scott Rothkopf "Modern Pictures" in Wade Guyton, Color, Power and Style, Exhibition Catalogue - Cologne: Walter Koenig, 2007

[25] Christy Wampole, "How to Live Without Irony", The New York Times, November 11, 2012 (first published on the "Opinionator Blog" then reprinted in "The Sunday Review"

[26] ibid.

[27] ibid.

[28] A reference to the endgame, or reductive modernism.

[29] As referenced in the essay "On Aggregators" from OCTOBER, vol. 146, Fall 2013

[30] From After Art, David Joselit, Princeton University Press, 2013. ISBN 978-0-691-1504404. (page 89)

[31] This idea references the key argument presented by Yves-Alain Bois in the chapter "Painting: The Task of Mourning" from the text Painting as Model, MIT Press, 1993. ISBN-13: 978-0262521802.

[32] This idea of how audiences now collect and store images on mobile devices without truly experiencing them was a central theme in a lecture in the session Painting as Subject by David Joselit, moderated by Joseph Koerner at the symposium Painting Beyond Itself: The Medium in the Post-medium Condition at Harvard University, April 12, 2013