"All things that spin. Also row. / There is inside it / something sun."

—Cole Swensen

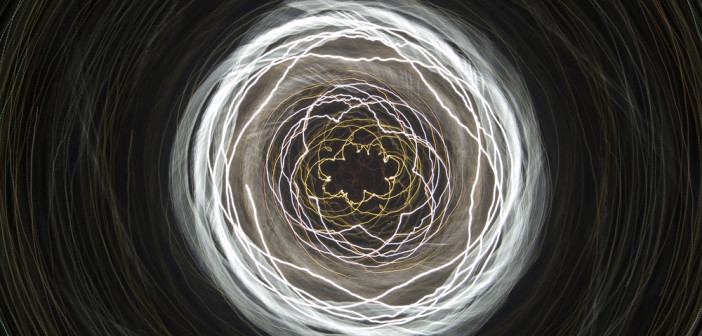

Two friends stand on a winter beach. Small cold waves hiss toward them on the sand. A fringe of seaweed that bears an uncanny resemblance to so much unraveled cassette tape makes a ragged outline of high tide along the shore. When the friends do not talk, which for long stretches they do not, they hear the sibilant repetition of the sea and, occasionally, the bass thrum of a boat’s motor or the baritone honk of a foghorn. On a tripod buried ankle-deep in the freezing sand, a camera turns at the end of a short wooden arm, which in turn rotates at the end of a longer arm, spinning in a wide circle. The camera points at the pier, whose length of streetlamps is occasionally struck through by the taillights of a passing truck. Robin Mandel says, "Oh, nice." The words come out of his mouth as white smoke.

Later, those streetlamps, on their alternating currents, will appear stitched like bright seams around and around the long dark exposure, and the passing truck will become an unexpected red streak in the luminous vortex. It seemed to me back then to be an experiment in physics—documenting light and time and motion in a way the eye could never see, so the mind must reach to understand. But it also seemed to be an investigation into what can be seen, if you have the right tools (including the ingenuity to imagine what most of us don’t think to look for) and what can never afterward be re-seen in the same way again. Robin Mandel reminds me that seeing requires our psychic presence and our rigorous willingness to run amok, and that the activity of seeing alchemically changes a streetlamp, or a lawn chair, or a fire hydrant, or a tombstone, or a mailbox, or a goat into something splendidly unexpected and provocative and funny, and sometimes—almost accidentally—sublime.

The art Robin has evolved from those early experiments in Provincetown not only reflects the maturing of what he called, in early days, "the contraption," but it also represents a full expression of the project’s potential. The most compelling art causes us to cease to take for granted the objects and materials and processes whose unnoticed presence comprises the furniture of our everyday lives and our consciousness. Here, a whirling pattern resolves itself into park bench, which in turn is not quite a park bench (as subject matter), but is rather or more importantly the source of the color and shadow and shape that (in motion) hypnotically transfixed us. And these pieces are not just evidence of and invitation to the activity of "re-seeing" a thing (plastic bag, garbage can, door), but the work of a truly clever and attentive mind playing with the relationships between these objects, as subjects for further (sometimes hilarious) consideration. "I love the idea," Robin told me, "of a winning combination." Living as I do in relative proximity to Las Vegas, it was not at all hard for me to see the spinning wheels of a slot machine or to hear the clatter of a roulette wheel in these pieces. But where these are devices of pure chance, there is a beautiful and seductive logic (or logics, for all are slightly different) to Robin Mandel’s combinations.

These pieces may spin and stop like slot machines, but their logic is sometimes more Rochambeau-esque, a philosophical game of rock-paper-scissors (fire hydrant trumps dog, because there are too many fire hydrants for one dog to mark, but woodpiles trump fire hydrants, as there are always more possibilities for disaster than there are contingency plans). But if this logic were simply to replicate itself again and again, it might cease to surprise. Happily, the best artists are often great tricksters—for instance, the finest writers I have ever known also tell the best jokes. A joke is a micro-narrative that surprises its audience into visceral response—ideally laughter, sometimes accompanied by shock or recognition or realization, or even a species of awe. The visual metaphor of a mailbox and a tombstone in Robin Mandel’s work is hilarious and lightly irreverent, but it also reminds us that if we can react with laughter or with giddy delight, we can also react with something subtler—realization, maybe, or foreboding, or longing.

So these pieces may be clever, but they are much more than that. They are evocative, allusive, and deeply compelling. Among other things, it seems to me, they are often about absence. In the simplest sense, they are mostly unpopulated, and the work prepares us for itself in such a way that when we are presented with bright primary colors in a yellow slide, a blue chair, a red fire-hydrant, we feel a kind of childhood nostalgia for picture books (what goes together?) and brightly colored board games and finger paints and summers that is only eclipsed by the interestingly post-apocalyptic absence of people and ketchup bottles and beer cans and Smokey Joes. The main characters of these pieces are garbage cans and manholes, the utilitarian infrastructure that stands a evidence to human presence, but un-utilized looks strangely abject. Like the carnival at night when the rides have shut down, the presence of the object makes the absence of its user curiously visible.

But the mind loves empty spaces. Considering "absence" from another vantage, theorist Jacques Lacan wrote of the mind’s desire to make a whole of the parts available to us, call it "paranoiac" thinking or Gestalt thinking, we are narrative creatures by all manner of inheritance. So the most interesting artists give that creative yearning a purpose—they give us the gutters between panels in a graphic novel, they give us jump-cuts in film, they give us line breaks in poetry. In Robin’s case, he gives us stories vectored within a series of images (a tombstone, a shovel, a manhole cover akimbo with a spray-painted word DIG arrowed toward it) and between them (rhyming with a gas meter, a shovel, a cemetery landscape, or contrasting with the trios of images that seem to be arranged by other logical modes in different emotional registers).

And these do strike a surprising range of subconscious chords, for here is a way of making something (a picnic table, a tow truck, a fence) beautiful without aestheticizing it, without falsifying anything about its actual appearance, without requiring any narrative about its origin or its significance, and without sentiment. Here is an artist who makes things beautiful with cameras not because he fixes them in a still moment, but because he makes them move. I’m reminded each time I watch this of the Russian Formalist poets and their notion of ostranenie or "making strange," their belief in the importance of alienating the self from its normal in order to keep it alive to the world. A mistake some artists make is to imagine this alienation is also from the self, from intuition or from delight—Robin Mandel never makes this mistake.

That play between the strange and familiar, between the curious and the felt, between the observed and the invented is central to Robin Mandel’s work. The poet Wallace Stevens once said that great poetry resists the intellect almost successfully. I feel that way about this art. I keep reaching for suggested taxonomies (things that are yellow, things that move in the wind, things that resemble things they are not) but every time I think I have a notion of what Robin is doing, I am (literally, beautifully) spun away from an easy association into something new. For while a dog may have a wink-some connection to fire-hydrants, equally or more importantly is the fact that a dog’s ear moves, as does laundry on a line, or a flag on a pole, or the shadow of the artist on the pavement tinkering with a "contraption" that happens to work on a similar axis to that of an amusement park ride in a neighboring frame. The subtle gestures that lead us from the twitch of a dog’s ear to the tilt-a-whirl keep us moving forward and back through the piece, turning around and around ourselves. Even at the "end," three panels whose different lines of perspective are all running themselves out into the distance, the fence in one of those final frames sends me back to the potential energy of a plastic bag hung on a fence post in a previous trio of images. Just when I think I understand the relation between things in Robin Mandel’s work, something changes.

Perhaps that brings me back to the beginning. To the spinning camera on the winter beach, to the two friends trying to invent new ways of drawing many disparate things into orbit around each other. To the sand that crunched underfoot like the crust of a crème brûlée against the back of a spoon. It is, I think, finally significant that Robin has included myself and others like me in his process. Yes, surely, it was better than being alone on the beach in January, but it’s more than that. In a way I do not see in the work of others, Robin Mandel thinks about seeing in a way that includes and even implicates him. He is not the fixed point at some disingenuous center, looking out, an authoritative gaze; he is also (as is everything he actively perceives) moving. Always moving.

- Robin Mandel Provincetown Harbor, February 22, 2010, 10:55 pm 2010 Archival inkjet print 12 x 18 inches

- Robin Mandel Provincetown Harbor, March 26, 2010, 9:26 pm 2010 Archival inkjet print 12 x 18 inches

The featured video work is:

Motion Studies, 2012

Single channel video, 4:00 loop

For additional information on Robin Mandel's work, visit his website www.robinmandel.net