We are fascinated by this word "experience." Just how to describe it? Something which cannot be touched by description, documented by exposure, or reduced by critique. You weren’t there... Experience is a lodestone of authenticity. The word keeps us out: we know that something strange and exciting has happened to someone, so exciting or remarkable that the person in question cannot delineate its components across ordinary language. This is to mean that what has happened must have had superior reality, beyond the pale of compromised and mediated experience. Excuse me: beyond the pale of compromised and mediated…what exactly?

"Experience", when used as a positive descriptor, seems to point to something specific, elevated, and primal. It is a slippery word when we come down from the heights of transcendence, for even on dull mornings it is still there, and it is still what we are doing. But not REALLY… We draw a line between real experience and its banal and quotidian opposite that might be called by the same name, probably in adolescence when we learn about things like romantic euphoria and drugs.

Does art create a sense of euphoria? I don’t mean the euphoria of romantic love, or even necessarily happiness, but I do think art might create a kind of euphoria that arises with a sense of meaning: participation in or sudden access to truth so richly present that it seems to have been there all along. Often it is thanks to some person, place, or thing that has been sufficiently transporting. As viewers, I dare to submit that we hope for this sort of thing from art. Artists, I also submit, encourage us to be somehow transported, even if we are more cerebrally transported by a sense of politics or history, even if the reshaping the artist performs is really an expression of their own ideas or experiences. In short, even if the form and method of this activity varies as widely as possible.

Experience is not actually indescribable. A more matter-of-fact reason for using experience is its ability to include the whole realm of sense perceptions, together with the sensation of time, in one neat bundle that can be understood at a glance. When artists are working in media that include all of these elements (not only the visual field but smell, sound, taste, time, kinesthetic response, and on) it is perhaps most pragmatic to choose a word like experience to describe what they have designed for us. For this reason, too, we might be tempted to think of experience as being particularly modern in what it describes: a word for an age where artistic practice might blossom into any realm of activity.

But already, here, we are in a fog. If the practice of an artist might include anything, and if what we ought to be doing as a viewer is experiencing, we might feel a kind of block on our language. If we wish to be intelligent consumers, we can only fall back cosmetically on the particulars of experience, knowing that the truth lies in a transporting synthesis, and that such synthesis is subjective. Thus, I will submit that we might experience a self-consciousness at backing away from well-defined conceptual space, and talking about what something is actually like. What is to be done? We might admit that quality is untouchable, knock it down to experience in casual conversation, and then talk about other more serious things—the genealogy of a form, academic concepts that relate to politics, history and allusion—in critical analysis.

James Elkins says of what he calls "poetic art criticism":

The goal of writing well is unobjectionable, and I hold it in mind as I write this sentence: but it just can’t have anything to do with the goals of art criticism. It can’t be a definition, or an ideal, or even a quality. It is too labile, and too flimsily linked to critical content, to be relevant to the project of trying to understand what art criticism has become.1

It may be true that "poetic criticism" is limited in the very ways Elkins describes. But it can help us, with practiced lability, to get at this surd experience, which I am suggesting becomes a catch-all word for some aspect of subjectivity that slips through the cracks. Experience doesn’t come up in genres of writing that are "relevant to the project of trying to understand what art criticism has become", but we talk about experience when we talk about art. We ought to be able to interrogate experience with some finesse, even if it means beating a retreat to something that appears flimsy.

So, here, with this polemic, I’ve been beginning a diary about my visit to the Paper House in Rockport, MA. I do not claim that it is related to a specific project of art criticism: instead I am trying to get at experience because I’ve been frustrated at the way the word is tossed at projects that involve participation or multi-sensory data as a vague catch-all beyond which nothing can be distinguished, talked about, or done better. The claim I make here is only that by writing about art differently we can learn something different.

ii. Soft Columns

I think of diaries as something for girls. Something is quite feminine about the word: for a man you would probably say journal, which in other languages refers to the newspaper. The object I imagine as a diary has a white cover and a tiny brass heart-shaped lock, and I wear the key on a chain around my neck. The object I imagine as a newspaper is tossed off of bicycles or hocked by boys in short pants and read by serious men in suits and fedoras, smoking and standing on street corners in the New York City of the 1940s.

Elis Stemnan was nearly finished with his Paper House by then.

If the medium is the message, there is an important object-hood to printed media. Even before the artist’s book comes into prominence as something for visual artists to pay attention to: Buzz Spector can wait, the news is hot and printed. Think of the sheer mass of every Sunday Times from every decade when the newspaper was indispensible. So much matter slugged off of bicycles and hocked on the street and tied in enormous bundles and used for shoes that was the source of information on the world. Now we listen and watch and read from screens. This means something else, to read as you are now reading, through a glass panel, to a place or a thing that is coded information that gives you the symbols that I have given as coded information into another device. The mechanism of exchange is more personified in the internet, which seems to be statically available for access: a utility rather than an object. The newspaper is finite. It comes in the morning. It takes up space on the unmade bed or the kitchen table or the café table after it’s read and spotted with something like marmalade. The textures of experience and pleasure attached to this particular kind of object are what the newspapers battled to remind us about, when it still seemed possible to preserve domination of information distribution in a significant and global way.

How did the word "column" come to be associated with matter for the newspaper? The resemblance, I guess, is an obvious one. But how did the word "matter" come to mean something immaterial like a piece of writing that could be printed in the newspaper? And if I were to take a job writing Dear Abby for a paper that stops print production almost immediately, would I still call a column what comes out as an awkwardly-scrollable rectangle slab, found at a hyperlink in italics at the bottom of the horoscope page? Probably I would. It will sound so nice, so old world, and adult to talk about my newspaper column.

Elis Stemnan, when he was alive in the early twentieth century, might have meant by newspaper column something else entirely. He wished to construct things, where I only wish to refer to them.

Stemnan began in 1922, with the help of his family, to prepare material to make the walls of a house out of Boston newspapers. He was interested in what could be done with the papers without destroying the print. Pasted and folded, the walls contain two hundred and fifteen thicknesses of newsprint, and are sort-of legible still through discoloring paste. The color has faded to a brown like finished wood, like dark maple, which is a logical but auratic color for it to have. Approximately 100,000 newspapers were used in the construction.

Text and writing fall somewhere between the world of ideas and the world of objects. This is nowhere more true than the Paper House, which as much as by Elis F. Stemnan, is haunted by Charles Lindbergh and President Hoover and the first World War. With the decline of print media, it is haunted by that ghost as well.

How valuable the content of these newspapers might be is debatable. There has always been a sense of the junk quality of newspaper: Leopold Bloom, reading "soft columns" as he shits "soft columns", then tearing up the paper to wipe. No great shakes in the words, but a satisfying use-value, all around. Matter to read, and matter to use. This kind of satisfaction with printed news would not be advertised by the New York Times. Neither would the Paper House. Good manners permit only some kinds of behavior with printed media. Curiously, unlike books, you can burn newspaper without a raised eyebrow: preserving the disposable periodicals too eccentrically is strange. But somehow Stemnan’s Paper House might fall into the realm of weirdo-type behavior. But here all is redeemed by object and nostalgia: Stemnan’s strange project with the equally strange content of the disposable news. Fluff articles about the British Royal Family, the Ku Klux Klan, and the preferred cigarette for 1931 all peek through worn shellac. We value them in their peeking differently than we would value them on microfilm. The columns are softer, their veneer more similar to the romantic one that surrounds the twenties in some dreams.

iii. The Fastener and the Beach House

By 1922, Elis F. Stemnan held several United States Patents. His inventions were not glamorous or eccentric, and many of the patents represent modest and practical improvements for everyday household goods: a sad-iron, a new type of snap for ladies’ garments, a machine for bending wire into paper-clips, a brass fastener. He was married. His wife played the piano, and the Stemnans had a summerhouse at Pigeon Cove.

There is a romance about a beach house. I drove up from Boston on a Thursday, one of the early summerlike days around the end of April, in a borrowed car with the windows down. For a stretch, route 95 is like any other hustling route to someplace; anything but a teenage appetite for elsewhere will fail to endow it much. This is boring driving. The same seems to be true of 128, which points out to the upper lip of Massachusetts. But after a stretch there is a change. Funny roundabouts, fewer lanes: the traffic slows and thins. Passing the Candy House at Rust Island, the landscape is suddenly romantic, suddenly right. Folly Hill near Prides Crossing. Rolling onto Story Street, past Lamb’s Heights and Sandy Bay, glimpsing the concrete furniture that banks the sea.

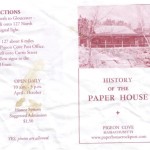

I thought it would be distant from everything. Photos of the Paper House give the impression of a place far off from anything, across a patch of rock and grass, the only thing for miles, and maybe on a hill. In fact the street is one of those rural residential streets that is almost crowded, and I pass the place once before I notice what I’ve done. It’s absolutely beside these other houses: all summerhouses. Their romance is null. They are places where people like a certain brand of dishsoap, eat cool-whip and packaged hot-dog rolls, wear coral-colored tank tops, and talk about the price of gas. It is so close to other houses (all scrupulously-groomed enough, with vinyl siding) that the photos on the website, suggesting isolation, must have been a feat of arrangement: the rock that peeks across the foreground is a breed of manicured rock-garden that features little sculptures from the garden center. There are mailboxes, lawn ornaments, and other stuff of regular life that prevent me from getting a good shot. There isn’t any parking, but this place puts me into a mood like a July between the years of high school: still streets bright and lonesome, filled with birdsound, unpoliced. I’ve put the car someplace that’s nearly a ditch, under a tree that’s blooming, knowing that I’ll draw attention from the windows on the street.

How do you get in? It seems too much a part of someone’s yard to just walk through the door. Their lawnmower is on the porch. Should I ring the doorbell? I don’t. What if it’s locked?

I go right in.

It’s smaller than anticipated. Two rooms. One with windows. It isn’t a place a person could live: it’s a play house. There is no bedroom. None of the kinds of rooms that would need running water are included. All of the furniture, like museums of decorative arts or turn-of-the-century theaters, seems slightly too small. The chaise lounge is the piece of furniture most caved and discolored by the human body. The chairs on the porch have an air of use. The writing desk looks untouched.

Stemnan and his wife had photos taken here: they’re printed on postcards. They both look rather earnest. Lined up on the table, the cards are sold by the honor system, which is also announced on the brochure as the general mode of operation. There is a jar for donations to a program that will help to educate distant children. All of this is somehow toothsome, pleasing.

Of course, the pleasure of places like this is recognized as a commonplace. "Outsider art", and our pilgrimages to it. From "inside", ostensibly. But inside of or outside of—what exactly?

In a gorgeous book edited by Leslie Umberger called Sublime Spaces & Visionary Worlds,2 published by Princeton University Press in collaboration with the John Michael Kohler Arts Center, the term "outsider" is noticeably eschewed, and this is creditable. Here Sabato Rodia is not an "outsider" artist, he is a "vernacular" artist. Erika Doss, in her essay "Wandering the Old, Weird America", quotes from Robert Duncan’s paean to the Watts Towers, "Nel Mezzo Del Cammin Di Nostra Vita,". Here are the two stanzas Ms. Doss selects from the poem:

Of course it is difficult to give the poem in full: it is long, and she is not provided the special privilege of hyperlink to exactly the right place. But what is definitely included here is the weird glory of the towers, and what is definitely omitted is a certain sense of Rodia as an artist. This is how Duncan ends his poem:

That the tone of this should be too ambiguous to open an essay glorifying the art of the "old, weird America" is certain, yet Duncan seems to ultimately offer Rodia praise. The ambiguous tone of the final stanza is also a mark of respect: it takes the project seriously enough to offer some view of the artist’s arrogance in leaving enormous relics of himself, which has its shadowy part, of which no artist, inside or out, is exempt. But Ms. Doss’s act of omission helps me to articulate something about the house at Pigeon Cove. For Elis Stemnan was a very different kind of person.

The Paper House does not risk height. It is a strangely subtle place, resembling "mean regular houses" and stuffed alongside them. Its quality, rather than bizarre ostentation is humility: Stemnan made fasteners. He experimented with paper—probably partly curious with his inventor’s mind about the qualities of newsprint, a cheap, often free material. He was not tortured by vandalism, as Rodia was (beginning construction the same year as Stemnan), and he did not violate any law. He worked in the city, and built at the locus of his pleasure and dreams: beside the beach house.

What is strange about the Paper House is how noticeably absent is a sense of frantic mania, willing to make a monument, however bizarre. If we are kept from thinking deeply about this assumed and generalized quality in vernacular art—the drive of the unrecognized artist to create wild environments—it is easy to use eccentricity as a rubric for evaluating our experience of these spaces. Really, that Stemnan seems not to have been eccentric is what makes his Paper House supremely odd. The experience to be had there is not immediately breathtaking, but opens onto a puzzle of human behavior that includes not only Stemnan’s act of building, but also any act of building, and the creation, distribution and recurrence of the printed news. And all of this is made rich by a weird poetics of decay: you see it especially in these photos of the outer walls of the house that I can’t help but include. Each inch of the house’s exterior is worth a specific delight.

The interest of the place, however, is not Stemnan’s separation from society, but his continuity with society, pushed to an extreme that canonizes quotidian life. It is either this, or the odor of shellac in dim light that gives the Paper House the feeling of a shrine. Pushing a five-dollar bill into the mailbox as I left, I was reminded of paying to light a candle at a basilica. This, some secular version: the Honor System.

And that was all. I drove away from the house. I went to stare at the sea.

[1] Elkins, James. What Happened to Art Criticism? Chicago: Prickly Paradigm Press, 2003.

[2] Umberger, Leslie, ed. Sublime Spaces & Visionary Worlds. New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2007.