As queer photographer and theorist Deborah Bright reminds us, by that perfect political moment in the mid-1980s, the AIDS pandemic had catapulted artists into the political fray, many of whom had lost friends, lovers, and colleagues to the disease. Against increased public censorship and homophobic rhetoric over the "deviance" of an LGBT community wracked by the disease, artists sought to create work that could engage and further their political struggles. The artistic political action group ACT UP, the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power, let the wider community know the untold cost of their silence.5 And in academia, as queer studies was burgeoning as a field of inquiry, the gay and lesbian caucus organized within the College Art Association to promote queer issues and activism within the arts. That event, in 1990, came on the heels of nearly a decade of intense debate between feminists over women’s relation to pornography and other sexually explicit images, later known to historians as the "sex wars."6 In the midst of heated political infighting within feminist and queer communities, and against the conservative backlash that, through congressional action, de-funded the Mapplethorpe exhibition and established stringent new regulations concerning "general standards of decency" for the National Endowment for the Arts, publications dealing explicitly with themes of sexuality flourished. As censorship increased, so too did the public conversation about queer art and activism. Within the short span of a decade, magazines and zines proliferated, including On Our Backs, the "sex-positive" response to 1970s Off Our Backs; Bad Attitude and Outrageous Women; books Coming to Power and Caught Looking; the mainstream The Advocate, Genre, and Out; lesser-known Poz, Ten Percent, and Girlfriends; Deneuve/Curve; and the countercultural JDs, Cunt, and Bimbox; Girljock, Bamboo Girl, Fierce Vagina, Jailhouse Turnout, Bitch Nation and more.7 While many of these publications were not fated to last long, they would during their heyday form part of what Michel Foucault calls a vast and "complex machinery for producing true discourses on sex," one connecting the "ancient injunction of confession to clinical listening methods"8 and, eventually, trade publishing. The explosion of discourse flowed from the countercultural current and up mainstream. By the early 1990s, the likes of New York magazine, Vanity Fair, and Cosmopolitan would present the subcultural styles of these earlier radical publications on their own covers as embodiments of the new look in fashion, "lesbian chic," drawing sharp criticism from within the LGBT community for their appropriation of queer signs for commercial purposes.9 Benetton Group would infringe further into the realm of queer activism, launching their "Shock of Reality" campaign in 1992 that notoriously featured Family in Ohio, an ad of a man dying of AIDS.10

The critique of fashion photography as appropriative, as commodifying queer images and identities for the heterosexual gaze, is one that has remarkable staying power, and is why Collier Schorr’s work is often neglected by queer artists and activists (her 1995 androgynous portraits from the series Horst in the Garden are, for instance, entirely absent from Bright’s influential The Passionate Camera). While fashion photography has long had a complicated, and often antagonistic, relationship with the art world, it is, even today, considered by many to be antithetical to queer photography. The avant-garde might shun fashion as vacuous commercialism, denying, in the process, their own relation to the commerce that drives the art market, but queer photographers, as activists, have more reason to be wary. Viewed as an appropriation of the authentic stylistic attributes of subcultures for the sham purposes of selling product, fashion photographs are, Kathryn Rosenfeld argues in New Art Examiner, insidious images that associate meaningful subcultural signs with a mainstream "idea of hipness and commodity fetishism."11 I do not agree that commercial photography is an inherently depoliticizing act. Like all discourses, it is political, and its strategies (and images) have both intended and unintended effects that can be put to one use one moment and the opposite the next. Even, perhaps, Family in Ohio, which photographer Paul Antick points out fused photojournalism with advertising to present a man dying of AIDS as a "Christ-like figure,"12 a narrative directly counter to the prevailing religious and political hostility towards those suffering from AIDS. The techniques of power, Michel Foucault has taught us, are polymorphous, forming a complex web of multiple and mobile force relations, within a system of tactics and strategies, that makes possible discourses that are used to support those relations.13 Along with Foucault, then, I will ask "Why has sexuality been so widely discussed, and what has been said about it,"14 specifically, in the works of Catherine Opie and Collier Schorr? While queer photography is most often made by lesbian and gay artists, it need not be. If queer theory teaches us anything, it is that heterosexuals too can be quite queer, though in practice they often are not. I am not interested, then, from an analytical viewpoint, in the gender or sexuality of any individual artist, but rather in the theories, commitments, or politics that motivate their work and its reception, variable though that might be. More to the point, I must ask: what nexus of "power-knowledge-pleasure" sustained the explosion of discourses on sexuality throughout the 1980s and well into the 1990s, informing and spurring Opie and Schorr’s work just as they were mastering their crafts at CalArts and SVA, respectively?

Catherine Opie’s segue from her thesis Master Plan, two-hundred documentary photographs investigating the strictly normative gated communities of Valencia, CA, to the critical dialogue around sexuality, then growing ever louder and louder in the art world and elsewhere, took the form of a series of thirteen formally classical portraits of herself and lesbian friends. Exhibited in 1991 at now-defunct 494 Gallery in New York, Being and Having was Opie’s first one-person show, and a formative response to Jacques Lacan’s psychoanalytic concept of women as being the phallus and men as having it.15 Dressed in drag, in intentionally noticeable fake mustaches and goatees, her sitters are female men. They play with gender, trying it on like a literal and figurative change of clothes. Opie figures as "Bo" within the series; others have still more playful names, "Papa Bear," "Pig Pen," "Chicken" and "Wolfe." The aesthetic of artificiality is heightened, with the faces of her subjects tightly cropped against a bright yellow backdrop. The framing that cuts off their foreheads was intentional, as Opie explains: "When you isolate the face and put a nametag on the frame, you emphasize the question of identity."16 That concern, the identities and identity politics of her community, was foremost in her mind, and would become a theme she later developed in subsequent bodies of work Portraits, Self-Portraits, and Domestic in her intense drive "to catalogue and archive the people and places around me."17 There is a continuity to her work in its concentrated investigation of communities and the individuals who comprise those communities, though as distinct series Being and Having could not be more different from her later work Domestic.

Catherine Opie had gotten into real gender trouble in Being and Having, a kind that would later become, to my mind, somewhat diluted by earnestness, as in her more recent photographs documenting domestic lesbian couples. While we cannot know for certain if Opie was aware of Judith Butler’s work (she claims she wasn’t),18 her 1991 exhibition coincides with the publication of Gender Trouble just one year prior in which Butler writes about the performativity of gender as reiterated actions that constitute the very identities from which they are said to proceed naturally. It should be noted that Butler is often misread as meaning simply "performance," intentional acts one undertakes to actualize one’s gender presentation or identity. But this is not the case; while drag is parody, it is not parodic of an authentic or original gender, as everyday enactments are also performative. Her thesis in Gender Trouble parallels and modifies Foucault’s own argument in The History of Sexuality that there is no given biological sex from which sexuality can be said to issue, but rather that the deployment of discourses about sexuality unite ontologically disparate functions, desires, pleasures and intensities, sensations, potentialities, and physical elements under the false unity of sex. That deployment proclaims biological sex as the cause and not effect of what is meant by sexuality, while concealing the mechanism through which it is created.19 To this mix, Butler adds the new term gender, enabling reconfigurations of the constellation of gender, sex, and sexuality (gender, for Foucault, is arguably already a part of sex). To some degree, Butler invites misreadings in her elaborations of the subversiveness of drag performance. But her idea that "parodic categories serve the purposes of denaturalizing sex itself"20 (and sex, for Butler, is already gendered), including not only drag but queer identities such as butch, femme, queen, and queer, provides a strong conceptual framework for parsing Opie’s Being and Having (or maybe it is that Opie’s Being and Having provides the visual framework for Butler’s Gender Trouble).

Because heterosexuality proscribes normative subject positions that are impossible to embody, contingent as they are upon the repetition of gender that can never be seamlessly coherent,21 it is a compulsory law, notes Butler, that is both a failure and comedic; that fact can be pointed to (not to mention, laughed at) through intentional subversions of gender in which the binary between "man" and "woman" is presupposed and intentionally proliferated beyond all coherence.22 Arguably, Catherine Opie takes a similar approach in much of her work, but nowhere is it more clear, to my eye, than in Being and Having. Drag is performative subversion precisely because it features, in Opie’s case, "women" dressed as men, a coupling of what is perceived to be a "reality" of gender with the "unreality" of drag. In such instances, Butler reminds us, we believe we know the difference between the reality of gender and the artifice or falsehood of the mere appearance of gender.23 Our sense of that gender reality is immediately called into question, though, as there is nothing that readily grounds our perception. The gender that is presented to us is masculine; we have no reason, then, to presume that the king’s "real" gender is feminine. Rather, neither gender is quite real. That, at any rate, is the upshot of Butler’s argument for drag and, arguably, Opie’s series of portraits in Being and Having,where she operates conceptually through discourses of gender performativity. This effect is doubled down on in photographic identity portraits, which are often taken to reveal some truth about their subjects but are always stylized by the photographer (even when that style is straightforward and unstylized). The identities of Opie’s sitters, however, parallel their gender presentations. They are not to be read as real identities but rather as a collective act for the camera. The uniform similarity of Opie’s portraits unites her subjects’ identities, presenting a type that straddles the boundary between reality and unreality. Both the photographer’s and her subjects’ apparent awareness of their condition separates the Being and Having series from traditional portrait photography.

Butler favors just this kind of parodic redeployment of heterosexuality within gay and lesbian practice, and queer gender identities, butch and femme among them, are said to do the trick of undermining notions of natural or original gender in the way drag is purported to do.24 Opie’s series Portraits and Self-Portraits, and later Domestic, follow in this vein, with an ever greater focus on identity and community over performance. It would seem that Opie, along with Butler, believes that queer gender identities, as they are lived rather than performed on stage, are politically subversive, or that she set aside her earlier concerns in Being and Having for other ends, perhaps the visibility of the queer community. As she explains, "I think it is important to have an involvement in the world and to make images that reflect on those ideas of how communities are formed and identity politics."25 Becoming more earnest and somewhat less playful, then, Opie would go on to create an almost encyclopedic compendium of portraits she collectively calls her "royal family," noting the influence on her work of sixteenth-century artist Hans Holbein the Younger, court painter to Henry VIII.26

Catherine Opie, Self-Portrait / Pervert, 1994

Catherine Opie, Self-Portrait / Pervert, 1994Chromogenic print

40 x 30 inches

Courtesy Regen Projects, Los Angeles © Catherine Opie

Treating her subjects with the painterly dignity they deserve, but have not usually been afforded in portrait photography, she would photograph fellow members of the leather S/M scene in San Francisco, drag kings and queens, FTM transsexuals, and performance artists such as Ron Athey, against rich, jewel-like backdrops. In this way, Opie could give visual legitimacy to underrepresented members of communities too often viewed as being on the fringes of respectable society. This act is a transgressive one, as Butler, in her keen observations of social documentary photographer Diane Arbus makes clear, "We are not supposed to make into visual spectacles human bodies that are stigmatized within public life or to treat them as objects available for visual consumption."27 In Opie’s work as in Arbus’s, we are invited to look at subjects we are not supposed to see; the revelation is that those subjects, condemned as "freakish" by normative social standards, are self-respecting individuals who often return our gaze or ignore our curiosity altogether.28 What is more, Opie, perhaps unlike Arbus, would like us to further see that her subjects are not freaks by any means.

On the one hand, this is the real strength of Catherine Opie’s portraits, apart from their obvious compositional and technical achievement, which needs no mention. In her exhaustive typological approach, Opie often draws comparisons to August Sander, whom she cites as a formative influence.29 Sander is most highly regarded for People of the Twentieth Century, his quintessential categorization of individuals by type. It is worth noting here that Sander’s categories were his own fabrications based loosely on social realities, intended to be read as such. While there is nothing to suggest that Opie definitely does not view her own subjects as her fabrications, her deep commitments to identity politics and queer communities seem to imply otherwise. I believe it would be far more accurate to say that Opie is concerned, first and foremost, with lived and political realities, with queer subjectivities as they are enacted performatively in the world. Her photographs, then, are to be read as portraits of subjects, not tokens.

This assertion is borne out by photographs such as Dyke (1993), Self-Portrait/Pervert (1994), and Transgender (c.1993). In each, the selfsame titles are inscribed on the flesh of Opie’s subjects with a razor blade or tattoo gun. These gestures were motivated by a source of pride in her subcultural community and as a rejoinder to "what was happening culturally in the US: The [NEA] censorship, the fuss around the Mapplethorpe show and what was happening in mainstream gay culture."30 Opie’s response to mainstream LGBTQ culture and its political efforts to normalize itself at the high cost of further stigmatizing queer and leather communities was visceral, indeed, written on her own chest in at least one instance.

Chromogenic print

40 × 30 inches

Courtesy Regen Projects, Los Angeles © Catherine Opie

These photographs, in particular, lend themselves to a Foucauldian analysis that can give us insight into the problematics inherent in Opie’s chosen strategy for representing sexual minorities. In Dyke, although naked, very little is revealed about the subject, whose back is turned on us as she sits for a formal portrait before an ornamental blue drape. We see that she is inked and has hooped piercings in her ears, and that she has shorn her hair. Despite the fact that we cannot see her face, or any other features that might suggest the semblance of an identity, we know from the tattoo on her neck that Opie’s sitter is a Dyke. No matter what she might do or desire, or how she might stylize herself in the absence of any partner, Opie’s subject is clearly a lesbian. The category is self-defining. Normal and Self-Portrait/Pervert work in a similar if more derisive way. Opie is well-known for her 1994 portrait of herself in a taut leather hood and collar against a lush golden-leafed backdrop. Surgical needles have been inserted in symmetrical rows up her forearms and biceps. In elaborate script, the word "Pervert" has been carved into her chest above a leaf-like flourish that mimics the drape behind her. It is a confession that is a source of pride for Opie, rendered as such, as part of her attempt to "document myself within that community."31 Against presumed expectations that subject matter of this kind should be freakish or spectacular, Opie has composed a formal, even regal, portrait. Transgender has a similarly clean presentation. It features a transman who, as in Dyke, is facing away from us. His bearded profile is stoic. The word "Normal" has been razored into his slender back, its cuts echoing the vibrant red background. We learn that he has not yet had a mastectomy, and perhaps will not elect to undergo the knife.

As a viewer, I am not quite sure what to make of Transgender. Opie herself is very clear when she remarks that "...language is embedded on the bodies of my friends and myself as a structure of identity."32 But meaning, after all, is slippery. Is Opie’s sitter proclaiming his rightful place as a decidedly normal subject, or is he, rather, mocking the mainstream conception of normality altogether? Is he normative, or is he not? There can be no singular answer. It is worth noting that Opie’s later series Domestic, comprised of portraits she had begun in 1995 of presumably monogamous lesbian couples at home, is markedly different from Transgender, and does indeed seem to embrace "the all-American ideal of home and family"33 in such a way that the inscription "Normal" is hardly necessary. This shift might be part and parcel of increased social acceptance for gay and lesbian persons, or it might reflect the personal desires of the photographer at different stages of her life, or the changing preferences of galleries and museums in a fluctuating art market. But, even in her earlier work, we must consider that Opie is engaged in a practice of portrait-making that has its theoretical grounds in a powerfully normative, even hegemonic, discourse about identity.

Catherine Opie has added a distinct voice to the already heated discussion of sexuality and identity politics that burgeoned throughout the 1980s in response to the AIDS pandemic and the conservative backlash that exploited the disease as grounds for its legitimacy. Working within the framework of that repression, Opie sought queer visibility and social acceptance for sexual minorities. The repressive hypothesis, as a psychoanalytic concept that pits such sexual liberation against the oppressive forces of cultural conservatism, is one with a long history; it is arguably entrenched in the public’s mind, and in Catherine Opie’s portraits. But what is truly "peculiar to modern societies," as Michel Foucault reminds us, "is not that they consigned sex to a shadow existence, but that they dedicated themselves to speaking of it ad infinitum, while exploiting it as the secret."34 We are tasked with the inexorable duty of telling "oneself and another, as often as possible, everything that might concern the interplay of innumerable pleasures, sensations, and thoughts which, through the body and the soul, had some affinity with sex."35 The repressive hypothesis, Foucault contends, is a ruse of power concealing its productive capacities. Rather, in modern society, it is confession itself that is demanded and that constitutes the subject through an unrelenting system of discourses. But because this obligation to confess is so deeply ingrained within us as the very fabric of our own identities, "we no longer perceive it as the effect of a power that constrains us;" it is instead perceived as the ultimate truth of our "most secret nature," that in failing to speak is constrained by social forces.36 And it is this same truth that seeks to speak in Catherine Opie’s portraits, against the backlash that would condemn and repress it.

Foucault traces the multiple discourses and power relations through which a norm of sexual development was defined, one which would provide the measure for all manner of perversions and classifications of sexual anomalies.37 Among those classifications was the "homosexual" as a type of person. Where sodomy was historically viewed as a forbidden act comparable to adultery, by the late nineteenth century, homosexuality had become the constitution and specification of a distinct kind of individual, "a personage, a past, a case history, and a childhood, in addition to being a type of life, a life form, and a morphology, with an indiscreet anatomy and possibly a mysterious physiology."38 Foucault describes in detail the origination of the "singular nature" of the homosexual, whose every action was attributed to the composition of his or her sexuality as the innate "secret" and "hermaphrodism" of the soul. Before this historical moment, and prior to medicalizing and psychoanalytic discourses, homosexuality was an activity one could choose to undertake, but not an identity one could assume. That all changed when the "psychological, psychiatric, medical category of homosexuality was constituted from the moment it was characterized," Foucault notes, in Carl Friedrich Otto Westphal’s 1870 article on "contrary sexual sensations."39 The homosexual, and later the heterosexual, had congealed into a type of person. As her portrait Dyke makes abundantly clear, it is the former that provides subject matter for Catherine Opie’s art and activism.

Opie leans heavily on the same discourses she seeks to subvert through her artwork. While it is the deployment of those discourses that "enables something called ‘sexuality’ to embody the truth of sex and its pleasures,"40 we must not conceive of them in a totalizing or monolithic way. Indeed, Foucault is quick to point out that discourses can be used for contradictory strategies as "tactical elements or blocks operating in the field of force relations."41 Using the same categories and vocabularies by which homosexuals were classified as the perverse Other of normative heterosexuality, queer artists can and do speak for themselves, even proclaiming the "legitimacy or ‘naturality’" of homosexuality.42 Arguably, Opie does just this very thing. But this is a precarious advantage, and a strategy dependent on the audience’s reception. Any reading of a text or artwork is contingent upon the viewer’s preconceptions. In my view, Opie is fighting the good fight, but using fire to combat fire. She must be commended as much for fighting as for her artistic mastery, but I have to wonder whether her chosen weapon is as suitable as it could be. As "open signs," her photographs conceal their constructions, presenting us with what appears to be a series of real typologies, an ethnography of actual people whose sexualities are offered up to our gaze as the true secret of their selves. The confessions of her subjects shore up a troubling discourse about sexuality as identity, in the process defining sex as simply that which a body is.

With Deborah Bright, I agree that meaning, whether arrived at consciously or unconsciously, is largely contingent "...on the viewing context and a viewer’s given psychic and social predispositions."43 The worry, then, is that progressive and regressive viewers can make very different, even antithetical, uses of Opie’s photographs, potentially going so far as to see them as proof positive that homosexuality is a perversion or mental illness or, as with Arbus’s images, as "pandering to the unseemly desire to gawk at what might seem aberrant."44 Even if the prevailing interpretation of Opie’s work must be that delimited by the art world, we cannot be certain that the discourses it engenders will ultimately help sexual minorities or further their causes. This is not commentary on Catherine Opie’s art, or the quality of that art, but on its status as activism and the theoretical underpinnings that motivate it. The discourse that underlies her social documentary portraits is one that defines sexuality as identity, and it has all the potency and charge of nearly two centuries of its making.

Interpretations in the art world can, of course, be quite conservative. Ethnographic photography that classifies and documents "the exotic Other," for example, has a notorious history, one that includes warm reception by museums. But the concern is greater still. The discourse of sexuality that informs and is perpetuated by Opie’s work is itself a fundamentally conservative one. This may or may not explain, in part, her commercial success, but it certainly could undermine her own more progressive aims. If Opie had intended her Being and Having series, for example, to document the Daddy/boy subculture in San Francisco, a practice of gay male sexual power differentials that had become popular in lesbian S/M circles at the time,45 there is no evidence that she succeeded in conveying that interpretation beyond the confines of her own community. Rather, her identity politics may work to obfuscate her message. The practice of Daddy/boy sexuality can be entirely enveloped by the overriding discourse of lesbian gender identity. The implications of the former will then go unreceived in certain wider circles, even the hegemonic circle of the art market that champions her photography and has its own received dogma.

In contrast, Collier Schorr’s approach to imaging appears to be prima facie apolitical. A successful commercial photographer, she credits fashion photography with drawing her into the medium.46 This is a somewhat unusual claim. Fashion is an arena that is fraught with controversy for queer and other artists. Fertile ground for sharp criticism, it is often considered to be, if not entirely oppositional to queer art and activism, then useless for furthering its progressive causes. The point is made particularly well by Bright, who contends "Inevitably in consumer capitalism, when subcultural styles catch on among white middle-class youth, it means big business, especially if their countercultural ‘look’ can be skimmed off from its politics with a minimum of fuss."47 Since the early 1990s, the line between fashion, documentary, and art photography has become blurred beyond recognition, but old hostilities and judgments linger. The commerce of the art world is effaced by this criticism, but fashion becomes indelibly stamped by it, despite the substantial overlap between the two. This conceit is at the crux of the argument against the "lesbian chic" phenomenon, but it does not appear to have dampened Schorr’s queer aesthetic or her high regard for fashion photography. She combines both masterfully in her recent 2008 publication Jens F.

Schorr had met her model, the German teenager Jens F., on a train in 1999, and proposed to photograph him; it was a collaboration that would continue through 2005. She had been struck by how closely Jens resembled Helga Testorf, the subject of Andrew Wyeth’s consuming series of over 240 drawings and paintings he would eventually assemble (after having kept his pictures a closely guarded secret from his wife for 46 years) into the book The Helga Pictures.48 Schorr decided then and there to recreate the Helga series, using Jens as her proverbial Helga. Sensitive to the challenges of photographing women in ways that were not "compromising on some level," Schorr had often taken the tack of photographing men in their place, explaining "I’ve always photographed girls. I’ve just used boys to do it."49 Jens F. would become a literal collage of the sexes, with Schorr using Wyeth’s original book as a kind of log for her own photographs of Jens, and later several other models, assuming Helga’s vulnerable and prostrate poses. She would cut up her photos and combine them in new ways with Wyeth’s original drawings, interspersing the two with scribbled notes. The result was a scrapbook of sorts, blending genders or seemingly ignoring them all together. Schorr’s approach followed a painterly tradition, albeit one that went against the grain, but in a style that was radically different from Opie’s, a kind of antithesis of the perfected final image in favor of the ongoing experience of viewing overlapping and unfinished work perpetually in progress. Eschewing the pronouncements of the art world, Schorr drew on the romantic realism of Wyeth, not by any means an accepted figure himself, to undertake a project that we can only assume would largely be unacceptable to a mainstream, heteronormative gaze: transforming a boy into a girl.

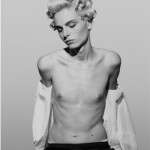

Collier Schorr, Untitled, 2011

Collier Schorr, Untitled, 2011Gelatin silver print

28 1/2 x 20 7/8 inches (72.4 x 53 cm)

Courtesy 303 Gallery, New York

© Collier Schorr

She diverges from Opie, too, I would contend, in her fluid understanding of sex, gender, and desire. Less concerned with identity politics than Opie, Schorr is able to freely explore the multiplicities of bodily experience, the scrapbook of poses and postures over the authoritative portrait. Her aesthetic in Jens F. is at play in her fashion photography, too, commercial though it might be, in which male and female bodies blend together through gesture, becoming nearly or even seamlessly indistinguishable. This ambiguity has long been Schorr’s aesthetic. Her recent photographs of Andrej Pejic for New York fashion magazine Dossier Journal feature the model with hair in curlers and painted toenails, a bow tied loosely around her neck, slipping off his button up shirt and tucking his hand down his pants suggestively. Her shoulders are so slender, and the line of her back so graceful, golden hair cascading between his shoulder blades. But Pejic is slender-breasted and appears to have an adam’s apple after all. Then again, her facial features are so feminine. But his torso is narrow. I will confess that I literally did not know the sex or gender of Schorr’s subject, who is undeniably striking and beautiful as is.

It is the same with Schorr’s photographs of Tamara Slijkhuis, who has a narrow torso and hips and seemingly more masculine facial features than Pejic, and stands tall dressed in high-waisted trousers and a white tank-top. Schorr not only chooses to photograph androgynous models, but her aesthetic heightens their androgyny. We think we know the gender of her subjects, but ultimately realize we do not. To my mind, it is remarkable that Schorr can draw mainstream audiences into a tacit acceptance of queer genders and sexualities, into a kind of complete disregard for the concept of biological sex that otherwise structures our lives forcefully (and often violently), without glossing over the radical implications of her position. "There’s something about shooting a model," she says, "where I no longer see it as a female or male body; I see it as a fashion body."50 I take Schorr at her word, finding the evidence of her assertion in the body of work she has created, one in which there is no truth of sexuality and its pleasures.

If Butler is right that "the notion that there might be a ‘truth’ of sex, as Foucault ironically terms it, is produced precisely through the regulatory practices that generate coherent identities through the matrix of coherent gender norms,"51 and I believe she is, then Collier Schorr is marking a departure from the prevalent discourses surrounding and producing sex as that secret of the soul, as it were. In abandoning the essentialism of identity as politics and practice, she opens the ontological status of sex itself to an exacting analysis of its own historicity. Her model for sexuality, and the desire that is commonly taken to underpin it as its causal principle, cannot be reduced to a parody of heterosexuality, as in Opie’s work. It has far more radical implications than that. Sex and gender become something a body does, and can do any way it pleases.

Like theorist Elizabeth Grosz, who draws on the writings of Giles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, I believe Collier Schorr seeks, in images beyond text, "to understand desire not in terms of what is missing or absent, nor in terms of a depth, latency, or interiority, but in terms of surfaces and intensities."52 Whether intentional or not, Schorr has taken up a Foucauldian mantle; for her, sexuality is not a natural given, restrained or uncovered by power relations, but rather a historical construct forged by those relations.53 How, then, does Schorr reconfigure gender and sexuality? With Grosz, I believe she makes sense of desire, that supposed interiority constitutive of identity, as a productive force, at once positive in its capacities and abilities. Never simply the feelings and affect of subjects, desire is a kind of doing or making that actualizes itself through surface effects at the site of bodies and their interrelations.54 The overlap of Jens F. and Helga is metaphorical as much as it is figurative, a kind of desiring that surpasses both heteronormativity and gay, lesbian, and bisexual sexuality. The field of Jens and Helga’s capabilities transgresses the parameters of sexuality as it is socially prescribed and proscribed. We can see this capability, too, in Schorr’s 1995-1996 photographs of Karin and Michelle. In the Garden, Karin in Grass shows an indeterminately gendered person lying in the grass, leaning on elbows and looking directly at us, legs bent at the knees. Karin wears binding around the breast, athletic socks, and white oversized underwear that is neither boxers, briefs, nor panties. Look closely. Karin’s bodily counters suggest that biological sex, too, is a question, not an answer. Desire does not give us guidelines; rather, it plays. Desiring Karin, who is attractive and handsome, cannot shore up one’s heterosexuality or homosexuality. It is more complicated than that. As sexuality, desire cannot be found in the ideologies that internalize a sense of self as a straight or gay man or woman. It must always be looked for, according to Grosz, "between one thing and another" in the form of "energies, excitations, impulses, actions, movements, practices, moments, pulses of feeling."55 Sexual encounters are never innate or pregiven. They are intensifications and multiplicities, all that bodies can do, and that is how they appear in Collier Schorr’s photography.

Collier Schorr, Blair Academy, 1999

Collier Schorr, Blair Academy, 1999C-print

16 x 20 inches

Courtesy 303 Gallery, New York

© Collier Schorr

Perhaps nowhere is this more clear than in Schorr’s photographs of wrestlers. Because Schorr understands sexuality and gender as labile forces, she is able to photograph cisgender males in subversive ways. She began her series of wrestlers, a project she has now been working on for several years, photographing the all-male Blair Academy wrestling team in New Jersey. Schorr transforms an arena that is all too easily read as hyper-masculine and strictly heteronormative into a scene of "medieval depictions of martyrdom."56 Viewing the wrestlers’ physical engagements as, in a sense, "total self-torture...all those things associated with saints, priests, monks and sometimes knights,’’57 Schorr is able to capture the performative actions of her subjects, the ways in which, together in a show of raw physicality, they are able to do masculinity. They flex their muscles, their faces contorting with physical endurance, locking grips and grabbing each other, both intimately and, ironically, in a way that is socially sanctioned. They hang from ropes and bars, stretching their torsos and arms as though on the wrack. Schorr speaks to the performativity of masculine gender and sexuality without, as she notes, relying on "subversively gendered subjects such as, say, transexuals."58 She is subversive in the most subtle way, within the supposed, but ultimately illusive, boundaries of heteronormativity.

Instead, Schorr allows us to view masculinity as a series of actions, forces, and potentialities that exist between bodies, without reducing them to the black and white terms with which they are too commonly associated, a tack she is very concerned to avoid.59 Rather, Schorr freely admits that she is interested in the manifold "reactions and interactions" that comprise the performative aspects of masculinity, the broad range of emotionality that can be expressed through the intensity of wrestling as sport.60 Even in this context, Schorr is not concerned with the sex of her subjects, as she makes clear: "...for me these guys are just a kind of raw physical material to use."61 Her process parallels her images in being a kind of activity that engages the body through the intensification of its surfaces. Schorr describes photographing her wrestlers as a kind of dance: "It’s so stressful because you’re dancing—I’m literally dancing in between thirty pairs of guys. But it’s so relaxing because it’s simply about eye and hand all the time."62 In this and other work, she struggles to represent men more fully in their "tenderness, vulnerability, physicality," without succumbing to the "gay male gaze" that would interiorize desire for her subjects as an expression of its sexuality.63 Rather, her interest is squarely on the transformation of the wrestlers through their heightened physicality. Schorr means this in earnest, viewing their matches as episodes of literal physical transformation. "I am merely taking frames out of their performances," she explains, "and the performance is as much masculinity or war as it is dance or spiritual ritual. They actually transform themselves..."64

It is this transformative capacity that sets her work apart. Schorr treats sex as doing, not as being, providing a visual framework for Foucault’s understanding of sex "as an artificial, conventional, or cultural alignment of disparate elements linked together" by the deployment of "discourses, knowledges, and forms of power."65 She gives the lie to the concept of sexuality as a natural kind, exposing heterosexuality as already queer, a series of actions and reactions. Put differently, I believe we can read Schorr’s corpus through the lens provided to us by Deleuze and Guattari; in privileging pragmatics over ontology, she allows the human body to be grasped conceptually in terms of what it can do and not what it is.66 This is a radical departure from prevailing discourses of sexuality, including those that form the groundwork for Opie’s critique of normativity. But why should we prefer one strategy to the other? Identity politics, after all, has been useful and politically expedient for the LGBTQ community, forming the framework for anti-discrimination laws and the legal argument for the right to marriage.

While granting the practical uses of identity politics, which rely on discourses that are widely known and accepted, it is my contention that those discourses can do as much harm as good in the long run. If we did not already view heterosexuals as a type of person, for example, with gays and lesbians comprising a distinct minority group of citizens owed equal protection under the law, there would be no conservative argument for restricting marriage to "opposite" sex partners for anyone (not even historical precedent, as the institution of marriage is historically contingent and mutable). In opening up the body to its own instability, Schorr, like Deleuze and Guattari, upsets the tidy ideas we share about what it means for anyone to be a subject with a stable identity, substituting "a thousand tiny sexes" in its place.67 There is, then, no there there in Schorr’s photography, no proverbial secret of the soul in sexuality. This not only allows us to conceive of what any body can do more broadly (perhaps having the added benefit of improving our sex lives in the process?), but undermines the structure of subject positions required by relations of domination and subordination. In removing the "artifice of unity and univocity" from what is in reality "a set of ontologically disparate sexual functions and elements"68 in a way that could only make Foucault proud, Schorr does not allow homosexuality, or heterosexuality, to be conceived of as legible categories. This is a tactic that could prove fruitful for queer activism. As Grosz points out, discrimination and social hierarchies, as structures of power, produce and rely upon systematically differentiated social positions for the social subjects they, in turn, create.69 We must ask ourselves, then, how invested we should be in those identities.

I am not suggesting that we should abandon the idea or reality of community, shared lived experience, or, in some cases, the expediences of identity politics, at least not all together and not in the short run. Rather, I am expressing a concern over relying too heavily on the very same discourses that have been used to pathologize and discriminate against gays and lesbians as the source of our supposed "liberation." As instruments of power, discourses can be used to shore up or expose and undermine those relations.70 However, as Grosz warns, we should not underestimate the ease with which dominant groups can produce meanings and representations for subordinate groups,71 or with which heterosexuals can redefine the discourses surrounding queer identities in even the most progressive art and activism, such as Catherine Opie’s, to suit social and political ends that are contrary to our aims.

Sex is not repressed through social prohibition, but rather is just that which one is obliged to confess ad infinitum as the secret of one’s identity. As a discourse, sexuality produces its own truth, forging our subjectivities and prescribing (and often proscribing) our pleasures as innate, natural, and normal, or otherwise pathological and perverse. It is, as Grosz contends, "in separating what a body is from what a body can do" that gender and sexual essence is produced.72 Catherine Opie, in her reliance on identity categories and politics, presents us with images of sexual subcultures that are open to interpretation, but which congeal the fixed and repetitive norms that constitute the discourse of homosexuality. Ironically, then, it may be Collier Schorr’s avoidance of politics that makes her photographs so powerful. The sexuality she documents is not one based on the determinateness of identity, but rather the indeterminateness of the fluid and mobile contingencies of making and doing. Her challenge to the heterosexual norm is one that, Grosz reminds us, has the power to strike at its "very self-constitution"73 in a way that Opie’s work cannot. It is arguably Schorr’s refusal to use sexuality and its pleasures as the basis of political aims and arguments that allows her the flexibility to redefine its terms so radically. While queer culture may never embrace fashion, and perhaps rightly so (I confess I am agnostic about that), we should not underestimate the potential of photography like Schorr’s to open up a space for reconceiving sex as force, energy, and impulse over depth, psychology, and interiority. It might do us good to be far less serious and far more playful, at least some of the time.

- Catherine Opie, Dyke, 1993Chromogenic print40 × 30 inchesCourtesy Regen Projects, Los Angeles © Catherine Opie

- Catherine Opie, Self-Portrait / Pervert, 1994Chromogenic print40 x 30 inchesCourtesy Regen Projects, Los Angeles © Catherine Opie

- Collier Schorr, Blair Academy, 1999C-print16 x 20 inchesCourtesy 303 Gallery, New York© Collier Schorr

- Collier Schorr, Forest Bed Blanket (Black Velvet), 2001C-print35 x 44 inchesCourtesy 303 Gallery, New York© Collier Schorr

- Collier Schorr, Untitled, 2011Gelatin silver print28 1/2 x 20 7/8 inches (72.4 x 53 cm)Courtesy 303 Gallery, New York© Collier Schorr

[1] Deborah Bright, "Pictures, Perverts, and Politics," in Deborah Bright, ed., The Passionate Camera, Routledge, 1998, p. 6.

[2] Jennifer Blessing, "Catherine Opie: American Photographer," in Catherine Opie: American Photographer, Guggenheim Museum Publications, 2008, p. 12

[3] Maura Reilly, "The Drive to Describe: An Interview with Catherine Opie," Art Journal, Vol. 60, No. 2, p. 83

[4] Vince Aletti, "Gender Blender: Collier Schorr’s collage of the sexes," Modern Painters, p. 36

[5] Bright, pp. 2-3

[6] Bright, p. 7

[7] Bright, p. 8

[8] Michel Foucault, The History of Sexuality: An Introduction, Volume 1, Vintage Books, 1990, p. 68

[9] Bright, p. 9

[10] Paul Antick, "Bloody Jumpers: Benetton and the Mechanics of Cultural Exclusion," Fashion Theory, Volume 6, Issue 1, p. 90.

[11] Kathryn Rosenfeld, "S/M Chic and the new morality," New Art Examiner, Vol. 28, No. 4, p. 28

[12] Antick, p. 98.

[13] Foucault, pp. 92-97.

[14] Foucault, p. 11

[15] Nat Trotman, "Being and Having," in Catherine Opie: American Photographer, Guggenheim Museum Publications, 2008, pp. 42-43.

[16] Trotman, p. 43.

[17] Reilly, p. 87.

[5] Bright, pp. 2-3

[6] Bright, p. 7

[7] Bright, p. 8

[8] Michel Foucault, The History of Sexuality: An Introduction, Volume 1, Vintage Books, 1990, p. 68

[9] Bright, p. 9

[10] Paul Antick, "Bloody Jumpers: Benetton and the Mechanics of Cultural Exclusion," Fashion Theory, Volume 6, Issue 1, p. 90.

[11] Kathryn Rosenfeld, "S/M Chic and the new morality," New Art Examiner, Vol. 28, No. 4, p. 28

[12] Antick, p. 98.

[13] Foucault, pp. 92-97.

[14] Foucault, p. 11

[15] Nat Trotman, "Being and Having," in Catherine Opie: American Photographer, Guggenheim Museum Publications, 2008, pp. 42-43.

[16] Trotman, p. 43.

[17] Reilly, p. 87.

[18] Trotman, p. 43.

[19] Foucault, p. 105; Butler, Gender Trouble, pp. 128-129.

[20] Butler, Gender Trouble, p. 167.

[21] Butler, Gender Trouble, p. 166.

[22] Butler, Gender Trouble, p. 173.

[23] Butler, Gender Trouble, p. xxiii

[24] Butler, Gender Trouble, pp. 168-169.

[25] Elisabeth Lebovici, "New York, Paris, London," MAKE Magazine, Women’s Art Library, p. 18.

[26] Blessing, p. 12.

[27] Judith Butler, "Surface Tensions," Artforum, February 2004, p. 119.

[28] Butler, "Surface Tensions," p. 120.

[29] Blessing, p. 13.

[30] Blessing, p. 16.

[31] Trotman, p. 72.

[32] Reilly, p. 93.

[33] Trotman, p. 120.

[34] Foucault, p. 35

[35] Foucault, p. 20.

[36] Foucault, p. 60.

[37] Foucault, p. 36.

[38] Foucault, p. 43.

[39] Foucault, p. 43.

[40] Foucault, p. 68.

[41] Foucault, p. 101.

[42] Foucault, p. 101.

[43] Bright, p. 5.

[44] Butler, "Surface Tensions," p 119.

[45] Trotman, p. 43.

[46] Aletti, "Both Sides Now," p. 4.

[47] Bright, p. 9.

[48] Aletti, "Gender Blender," p. 3.

[49] Aletti, "Gender Blender," p. 4.

[50] Aletti, "Both Sides Now," p. 4.

[51] Butler, Gender Trouble, pp. 23-24.

[52] Elizabeth Grosz, space, time, and perversion, Routledge, 1995, p. 179.

[53] Foucault, p. 105.

[54] Grosz, pp. 179-180.

[55] Grosz, p. 182.

[56] Craig Garrett, "Collier Schorr: Personal Best," p. 1.

[57] Garrett, p. 3.

[58] Garrett, p. 4.

[59] www.art21.org/texts/collier-schorr/interview-collier-schorr-wrestlers-love-america

[60] www.art21.org/texts/collier-schorr/interview-collier-schorr-wrestlers-love-america

[61] Garrett, p. 4.

[62] www.art21.org/texts/collier-schorr/interview-collier-schorr-wrestlers-love-america

[63] Garrett, p. 1.

[64] Garrett, p. 4.

[65] Grosz, p. 212.

[66] Grosz, p. 214.

[67] Grosz, pp. 184, 214.

[68] Butler, Gender Trouble, p. 137.

[69] Grosz, p. 208.

[70] Foucault, p. 101.

[71] Grosz, p. 209.

[72] Grosz, p. 227.

[73] Grosz, p. 226.