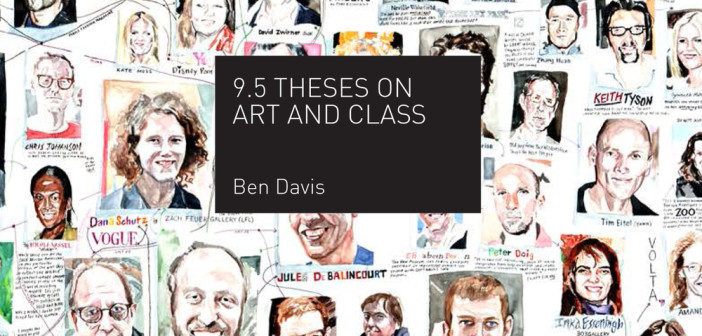

Last Tuesday, critic Ben Davis delivered the SMFA’s Beckwith Lecture on the subject "Art and Class," attempting to clarify the professional role of artists and, separate from the experience of an individual, where art stands in the culture.

A good portion of Davis’s material circled the sentiment that "inequality matters more to most artists than the art boom," although he covered the topic more thoroughly in his recent piece "No, Artists Aren’t the Winners of the New Gilded Age." The artnet article at least acknowledged outright that the tension Davis is focused on is occurring among full-time practicing artists caught between their exploitation by the art market and their misalignment with true working class oppression. At the lecture, Davis focused on his view of the present identity crisis of artists, interpreting it as their misunderstanding of what it means to be middle class and assigning them the historical definition of an independent artisan in contrast to today’s largely managerial middle class. While that is interesting and informative, it does not feel all that relevant to a discussion of how actual working class artists fit into their larger communities and culture, and the generalization might do more harm than good. He throws down a gauntlet, "either it’s just work or it’s mystical," suggesting that artists should stay away from labor as a conceptual topic and keep art out of working class struggles. It is a strange request for a group that he considers to be the face of creative industry, since no one seems to be asking writers or musicians to quantify which parts of their jobs are shaped by their creativity and which parts are merely tasks to complete.

Davis finds art workers’ attempts to express solidarity with wage laborers misguided and ultimately overshadowed by differences in political concerns. It is a narrow argument, and he used carefully selected examples to support it. He discussed, for example, Robert Morris’s trajectory through his 1970 solo show at the Whitney Museum, from highlighting and collaborating with construction workers in the gallery to calling off the show in the wake of the Hard Hat Riot. Davis did not choose an artist like Mierle Laderman Ukeles as an example, who, a year before Morris’s project, wrote her Maintenance Art Manifesto and began a performance career elevating wage labor and the unpaid, unrecognized work of women who are wives and mothers. Her project Touch Sanitation, in which she met and thanked 8,500 New York City sanitation workers, could have just as easily been cited if one wanted to demonstrate that an artist might work from the marginalized parts of their identity and reach out to others in a show of solidarity.

The second-to-last question of the evening came from a student, who asked if Davis exclusively meant full-time artists when referring to professionals in the middle class. It was the only point in the lecture when Davis acknowledged that the working artists he was discussing do in fact come from an upper level of a severely stratified profession. He stipulated that focusing on people for whom artmaking is their exclusive livelihood was meaningful because "that’s the dream," suggesting that all artists who have autonomy in the studio subscribe to the "middle class ideal to have professional identity overlap with personal desires."

The trouble with this assumption, however, is that it does not represent the vast majority of younger artists for whom Davis’s dream is insubstantial and unattainable—a pipe dream. Plenty of wage laborers today have interests and educational backgrounds in fields that remain closed to them despite their expertise. If anything, visual artists seem uniquely equipped to manage the pitfalls and disappointments of the current job market. In strong communities, artists tend to be resourceful about cobbling together livelihoods in diverse ways, to support each other so that those who have not broken through the professional bubble don’t feel like dilettantes for continuing their pursuits. It is worth recognizing that an artist might be persistent in the studio because it helps shape a meaningful life, even if wage labor is an equal or greater part of their day-to-day reality. Agency in the studio is a powerful force, maybe moreso for the alumni of BFA programs who must also be waitstaff and farm laborers than for those who have successfully navigated the prescribed system and act as their own bosses.

In a city like Boston, visual artists are confronting the gap between what they do for work and those professions that benefit from the emphasis on a creative economy. Accepting Davis’s thesis as relevant to all art workers—whether they are broke students, adjunct faculty, or wage laborers—misses some of the most crucial issues in our communities. We wind up in a conversation like the gubernatorial forum hosted by Create the Vote last July, where a panel of candidates tried to prove that they are capable of connecting personally with art in order to demonstrate that they value its state-level funding. That night at the Hanover Theater, a single candidate spoke to the problem of unpaid internships. No one raised a question about the impact a livable minimum wage might have on artists who must have both jobs and personal practices. Wherever that conversation is actually happening is where we ought to focus our attention.

- Ben Davis’s 9.5 Theses on Art and Class published by Haymarket Books, 2013