On bright, cold mornings in September, the Five Colleges of the Connecticut River Valley vie for the title of "Most Autumnally Attuned Campus." But this fall, Mount Holyoke offers a sublime experience that surpasses even the botanical gardens of Smith and the leaf littered quads of Amherst: a rare opportunity to view the drawings of Henri Matisse (18691954).

Matisse Drawings will run through December 14 at the Mount Holyoke College Art Museum. Curated by Ellsworth Kelly, himself one of the most notable American abstract artists of the 20th century, the show highlights 45 of Matisse’s seldom exhibited sketches, studies, and finished works. Some of these drawings have never even been framed before now.

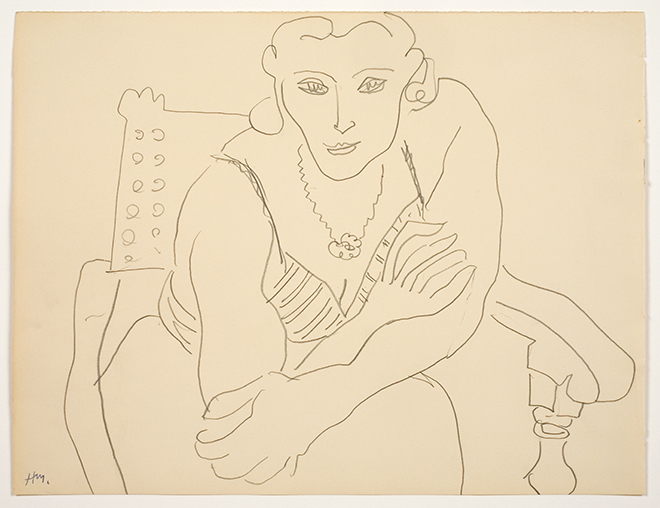

Henri Matisse

Henri MatisseFemme en fauteuil (Woman in a chair), 1935

Pencil on paper

346.203120

© 2014 Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Women are the subject of most of the pieces on view. Noting Matisse’s "economy of line," John Stomberg, director of the museum, describes in a press release how the artist successfully employed simple curves to explore the psychic space of his sitters, imbuing his images with each woman’s "emotional tenor." But the drawings suggest that Matisse had access to even more than the sitters’ thoughts and feelings. To view each sketch is to feel the spatial intimacy between artist and subject the corporeal immediacy.

It’s almost as if Matisse produced these drawing on a romantic whim, with whatever materials he found lying around each woman’s bedroom an eyebrow pencil from her vanity, a mascara wand from her handbag. And there seems to be an element of gentle mocking in the way the artist renders his subjects’ forms, with all their women’s things the trappings of their femininity. For a ring, he scribbles an asterisk across the fingers of a folded hand. A violent wave is meant to indicate a frilly sleeve or bracelet.

The show is mostly composed of works produced between 1930 and 1950, a period during which women’s identities ping ponged as they were called back and forth from their kitchen and their sewing table to the factory floor. With women taking on war work and jobs vacated by enlisted servicemen, the seams of traditional conceptions about gender began to show. The pinnacle of feminine adornment the peekaboo bangs made popular by the actress Veronica Lake was sacrificed, as so many other things were, to the war effort. A newsreel from the period demonstrated why women should "put glamour in its proper war-time place, and face the the world with both eyes in the clear." Ms. Lake herself instructed women to pin up their hair in elaborate conical structures (see Matisse’s Head of a Woman (1947) so that they might protect themselves from grizzly mishaps with the machinery that they were lately hired to operate.

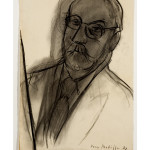

Tête de femme (Head of woman), n.d.

Ink on paper

423.205025

© 2014 Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

With women at mid-century temporarily doing away with all of their women’s things, we began to embrace wider definitions about what a woman looks like, and what a woman does. In capturing this particular historical moment, the organization of the exhibit at Mount Holyoke seems prescient, given college’s announcement earlier this month of a new policy that formally welcomes applications from any student who is female or identifies as a woman. As one of the last bastions of single-sex higher education takes steps toward embracing transgender applicants and the potential for evolving models of femininity, Matisse’s drawings though they quite literally outline the shape of women simultaneously echo the sentiment that gender is never so clearly delineated.

- Henri Matisse Femme en fauteuil (Woman in a chair), 1935 Pencil on paper 346.203120 © 2014 Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

- Henri Matisse Grand autoportrait (Great self-portrait), 1937 Charcoal on paper 507.206136 © 2014 Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

- Henri Matisse Tête de femme (Head of woman), n.d. Ink on paper 423.205025 © 2014 Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.