Declared "Photographer’s Row" in 1914 by Photo-Era Magazine, Boylston Street bustled with artists of all media in the decades just before and after the turn of the 20th century. With the Museum of Fine Arts and the Boston Public Library in Copley Square, Boylston and the Back Bay nurtured many vibrant arts organizations, such as the Boston Art Student Association, the Arts and Crafts Society and the Boston Art Club, in addition to a sizable art market along Newbury Street and studio spaces within private homes. Many of these spaces were occupied by women who, benefitting from Progressive Era reforms and urban changes, made their lives and careers as professional artists. Curated by Caroline M. Riley, Jan and Warren Adelson Fellow in American Art at Boston University, Craft & Modernity: Professional Women Artists in Boston (1890-1920) presents the lives and work of six of these women artists: Alice Austin (1862-1933), Edith Brown (1872-1932), Sara Galner (1894-1982), Edith Guerrier (1870-1958), Mary H. Northend (1850-1926) and Ethel Reed (1874-1912). Working across media, these women adopted professional personas in order to promote their work to clientele (which included book publishers and private patrons), share ideas or work and to build a cultural community. Riley introduces the complex political and cultural dynamic within Boston and Boylston Street (which was also home to the Women’s Anti-Suffrage Association of Massachusetts), before exploring the photographs, objects, prints and illustrations that these women artists produced while working in the city. What follows is a brief exchange with Riley discussing some of the themes presented in Craft & Modernity.

Your exhibition and catalogue very succinctly examine the lives and careers of six women artists, each working in a variety of media, during a very artistically rich period in Boston. How did you select each of the artists presented in Craft & Modernity?

I started with a list of twenty Boston women whose artistic production between 1890-1920 I found evocative and worthy of additional study. Through a process of elimination, I excluded artists whose work could not be located or who had too small an archival imprint. Thus these six extraordinary women emerged and I began to flesh out the intricacies that intersected their lives.

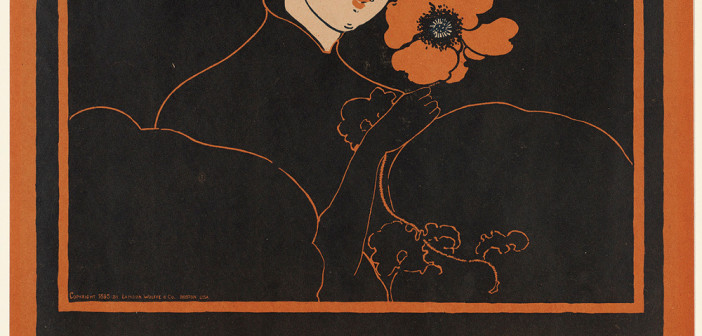

Ethel Reed, The Arabella and Araminta Stories, 1895

Ethel Reed, The Arabella and Araminta Stories, 1895Lithograph, 23 5⁄8 x 15 3⁄4"

Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

In your catalogue essay, "Meeting on Boylston Street: Professional Women Artists, Institutions and Commerce in Boston Between 1890 and 1920," you discuss how Boston, with public transportation, a postal service, and an intellectual, Progressive atmosphere, served to cultivate the careers of these artists. Will you speak more about Boston as a cultural space within this period compared to other American cities? Do you think Boston was more welcoming of professional women artists in this period than, say, New York?

While I can not speak to the complexities of New York’s art market and the strategies women artists employed there, I will say that the developments in Boston permitted women greater access to disparate parts of the city and the postal service’s 1 cent postcards proved an inexpensive and efficient means of communicating with their employers, sitters, and patrons. Further, those artists that set up studios and residences in the Back Bay clearly benefited from an emerging artistic community during the 1880s and 1890s that persisted until the 1920s when competition became too great. The mail itself is fascinating form of communication, compared with meetings in person, in that it is to a certain degree genderless. These 1 cent cards easily read by curious mailmen could pass through doorways that the women themselves could not have entered.

Most of these women artists worked with or around highly influential, wealthy (and Progressive) women, such as Helen Osborne Storrow. Each of these artists created a professional persona, attracting and maintaining clients within the city. Can you speak to the patronage that these artists received in Boston?

The women had different patronage systems. Northend used her friends and neighbors as the source material for her articles, publications, and lectures. The occupations of Austin’s sitters included a university president, a sculptor, and women such as Mary Perkins Olmsted, who worked in her husband’s office, as well as the children and still unidentified women. Further, families brought their children to her Boylston Street studio believing in Austin’s eye and tonal photographs. For Brown, Galner, and Guerrier, the patronage system was much more complex as they sought wealthy clients, who commissioned custom pieces, as well as standardized designs that were sold in their Boylston Street shop, their studio and eventually in Washington, D.C.

Austin, Brown, Galner, Guerrier, Northend and Reed each supported themselves from their artwork. In your essay, you discuss the challenges they each faced in doing so, especially in regards to finding affordable housing. Finding affordable housing (and work space) is a particular obstacle for many artists working in Boston today. What do you think contemporary Boston artists could learn about building a sustainable professional career from these six women?

In general, the women’s ability to be flexible in their definition of "studio" and to many times merge their work places and residences permitted them greater economic freedom. Further, it allowed them to play on stereotypes proscribed to women on the ideals of the domestic space. One of the things that I found most interesting was that the women often stayed within the same neighborhood as their careers improved or declined. For example, as Austin struggled financially, she would move to less expensive residences within the same few blocks on Boylston Street, or even within the same building. It was clearly a strategy to work within a known environment rather than try a completely new neighborhood. In the case of Paul Revere Pottery, when the women moved to a more expansive studio in Brighton in 1914, they kept the shop on Boston Street in large part to keep the same customer base. When Reed traveled to London, she at first had great success working for The Yellow Book but, within a few years, began to struggle, became more isolated due to her substance abuse, and was financially unable to return to Boston.

- Ethel Reed, Folly or Saintliness, c. 1895 Lithograph, 20 3⁄8 x 14 15⁄16″ The Trustees of the Boston Public Library, Print Department

- Ethel Reed, The Arabella and Araminta Stories, 1895 Lithograph, 23 5⁄8 x 15 3⁄4″ Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

- Alice Austin, Cyrus E. Dallin, c. 1914 Platinum print, 7 7⁄8 x 5 7⁄8″ Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

- Paul Revere Pottery, Decorated by Sara Galner, Pitcher, Three Ships design , 1912 Earthenware with glaze, 6 3⁄8 x 3 1⁄2″ David L. Bloom, MD and Family

Craft & Modernity: Professional Women Artists in Boston (1890-1920) is on view at Boston University's Stone Gallery through Friday, December 19.