The Rose Art Museum at Brandeis University is known for delivering powerful exhibitions rooted in contemporary thought and academic pursuit. Rose Art Projects, their new series of curatorial ventures, is a series of projects, each consisting of three separate exhibitions, dedicated to the exploration of a scholarly theme. The first in the series is curated by Katy Siegel, Curator at Large, and examines the delineations between representation and abstraction through artists who refuse this binary divide.1 Last Spring, work by Wols and Charline von Heyl comprised the first edition; currently the second installment of the first project is on view through December 21, 2014. 1914: Magnus Plessen is on view for the one-hundredth year anniversary of the start of World War I. An examination of the visual rhetoric of war, it combines the work of Magnus Plessen, a contemporary Berlin-based artist, with artworks by Otto Dix and Abel Gance, as well as historical photographs and objects.

Plessen's work begins with War Against War!, a bookwork by Ernst Friedrich published in 1924. The thick volume is purposely didactic, and its anti-war rhetoric is palpable through Friedrich’s editorial decisions. The book’s anonymous photographs (many of which were officially censored by government) were drawn from various archives and turn from descriptive images of war-ravaged landscapes to stomach-turning depictions of wounded soldiers.2 With helmets not regulation in trench warfare, the advent of the machine gun resulted in horrific facial wounds on soldiers caught poking their heads up to glimpse the field of battle.3 The medical photographs of these injuries contained in War Against War! are especially anonymous: missing eyes and noses erase personal identity from faces.

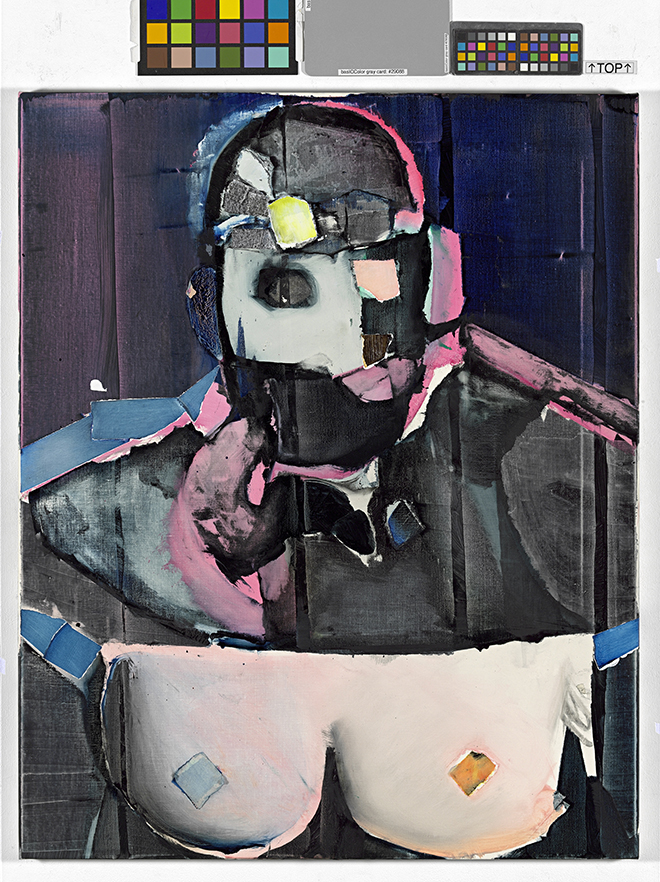

Magnus Plessen Ohne Titel (7), 2014, Oil on canvas, 96 x 78cm, Courtesy of the artist and Konrad Fischer Galerie, Berlin

Magnus Plessen Ohne Titel (7), 2014, Oil on canvas, 96 x 78cm, Courtesy of the artist and Konrad Fischer Galerie, BerlinPlessen's paintings are a reaction to, and simultaneous abstraction of, these images. Distorted figures, barely recognizable as human, are cut apart and rearranged. They emerge from soft, black backgrounds that absorb and negate light. Flat brush strokes cut aggressively through the canvases and function as injury and subsequent bandage. In these works, there is a simultaneous dressing and undressing of the timeless wounds of war. But the paintings go beyond a simple examination of the visual rhetoric of conflict; they become a critique of the social infrastructure of post-war attitudes. At Sidcup, the British hospital for the facially wounded, benches meant for the wounded were painted blue to signal to passersby that they should advert their eyes.4 Plessen’s The Blue Bench questions our desire to look away, showing blue bars that fail to support a body that crashes to the ground. Likewise, Untitled (7), shows breasts that are foregrounded as simultaneously revolting, alluring, and suggestive of the loss of sexuality these soldiers felt following their disfigurement.5

Interspersed with Magnus Plessen’s paintings are works by other artists. Otto Dix’s print cycle, The War, recounts personal experiences in the battlefield of World War 1, referencing Goya's famous series. Abel Gance's film also derives from personal experience and is strongly anti-war: the film cycles from pro-war patriotism through devastating loss, ending with maimed soldiers returning home to confront those who supported the fight. The inclusion of these pieces grounds the abstract interpretations of Plessen's work, footnoting his contemporary interpretation with historical reaction.

WWI soldier facial reconstruction casts and masks, ca. 1918 / American Red Cross, photographer. Anna Coleman Ladd papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

WWI soldier facial reconstruction casts and masks, ca. 1918 / American Red Cross, photographer. Anna Coleman Ladd papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.In between artworks, historical objects collectively tell the story of the artist studios that took over once reconstructive surgery failed men with severe facial wounds. In these studios, run by Francis Derwent Wood and Anna Coleman Ladd, plaster casts (called life masks) were taken, then used as a base to sculpt a prosthetic mask made of thin metal. These were painted as realistically as possible, and usually held onto men’s’ faces with spectacles. One such prosthetic is on display in 1914, floating in a case, and emphasizing its missing body. Archival photographs are on exhibit above cases that hold the stoic white life-masks of now-passed soldiers. Reduced to form, we encounter the horrors of the injuries without being wrapped up in graphic depictions of blood and flayed flesh.

None of these typical visual tropes of war are on display in 1914. Instead of the brilliant red that signals violence and destruction, the lack of bodies in the show is more potent than their presence, signaling death in a manner that gestures towards pain without screaming. Simultaneously, the show is a critique of the social disgust of looking at the wounded. Soldiers whose faces (and identities) were intact were used as media examples of heroism, but once identities disappeared, so did the celebration of their service.6 This show is a resurrection of the wounded as warriors and a larger critique of the society that sought to cover them up.

Within the gallery space, these contemporary paintings function seamlessly with the historical objects, begging the question of which actually chronicles and documents history. This curatorial ambiguity places responsibility on the viewer for extracting information and understanding the complexities of the underlying academic conversation not fully explicated in the wall text and program materials. After trimming away the horror of looking and its societal implications, the relationship between painting and reconstruction of the body comes to light. Portraiture has always sought to represent its subjects as lifelike as possible, here purposely subverting itself to cover political wounds and return faces to a static representation of what they 'ought' to be. Moreover, our identities are as much constructed by invisible lines, drawn by our societies to delineate what we will and will not look at, as by the images we actually see.

The examination of these soldiers’ identity foregrounds a current preoccupation with identity, both personal and national. In the United States, we are a people divided by political impulses and desires. Today’s version of war is fought from afar and US civilians are not aware of atrocities happening overseas save for the mediated knowledge fed to the public via media streams. We rarely see the impact on individuals or feel it first hand. But here, we are faced with the visceral effects of military decisions, and looking closely at these images, we feel them in our bodies.

- Magnus Plessen Ohne Titel (Klavier), 2014, oil on canvas, 105 x 190.5cm, Courtesy of the artist

- Magnus Plessen Ohne Titel (7), 2014, Oil on canvas, 96 x 78cm, Courtesy of the artist and Konrad Fischer Galerie, Berlin

- © Imperial War Museum (Q 30455)

- WWI soldier facial reconstruction casts and masks, ca. 1918 / American Red Cross, photographer. Anna Coleman Ladd papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

- WWI soldier facial reconstruction documentation photograph, ca. 1920 / American Red Cross, photographer. Anna Coleman Ladd papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

[1] "Rose Art Projects 1A," Rose Art Museum, accessed November 28, 2014, http://www.brandeis.edu/rose/onview/spring2014/roseprojects1a.html

[2] Martin Parr and Gerry Badger, The Photobook: A History Volume II (New York: Phaidon, 2006), 213.

[3] Caroline Alexander, "Faces of War," Smithsonian Magazine, February 2007, accessed November 26, 2014, http://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/faces-of-war-145799854/#6IFi3RvL2VFIfB2J.99

[4] Biernoff, S. (2011). The Rhetoric of Disfigurement in First World War Britain. Social History of Medicine, 24(3), 666—685. doi:10.1093/shm/hkq095

[5] Katy Siegel, Curator at Large at the Rose Art Museum, speaks about the specific functions of paintings in 1914: Magnus Plessen program materials.

[6] for more discussion on this subject, see Susanna Biernhoff, "The Rhetoric of Disfigurement in First World War Britain," Social History of Medicine vol. 24, no. 3.