I do not see why the loss of faith in the known image and symbol in our time should be celebrated as a freedom. It is a loss from which we suffer, and this pathos motivates modern painting and poetry at its heart.

-Philip Guston, from the catalogue for the 1958 Whitney Museum of American Art exhibition, Nature in Abstraction.

Philip Guston’s late return to figuration haunts contemporary painting. His presence is so heavily felt in the work of so many, it’s surprising that an exhibition on his continued influence wasn’t conceived earlier. There is a sense of inevitability to The Guston Effect at Steven Zevitas, a show that makes a broad, convincingly argued statement about the lingering spectre of Guston in the work of dozens of painters. It’s a densely hung, salon-style exhibition, but doesn’t feel crowded. The arrangement of the space carries enough intention to inspire meaningful connections, and those pieces that need to breathe have enough space to do so.

Guston was an artist of intense contradictions. The exhibition acknowledges this, with clusters of works that underscore the many varied particulars of his complex output and their burrowing influence. An invitation to look at contemporary painters through the lens of a major forerunner draws new associations out of familiar work. Little mimetic signatures pop up throughout: clumsy hands and feet; the palette of reds and greys, and nervous patches of brushwork that speak to Guston’s searching hand.

Brian Calvin Fingers, 2014, acrylic on linen, 30 x 30 inches. Image courtesy of Steven Zevitas Gallery

A small Brian Calvin painting illustrates this idea well: a circle of cartoonish fingers pointing accusatorily at the empty horizon at the center of the painting, empty except for the pronounced, questing little brushstrokes that make up the canvas—a central void foregrounded much like those in Guston’s mid-career abstractions. The subject in Swim Smoke Cry, a gouache by Dana Schutz, is a clear homage: a bulbous, weepy face half-underwater, a lit cigarette hanging from the open mouth. But beyond the obvious connections are more subtle cues, like the swimmer’s hand, fat and too small and rendered in a tentative, broken line akin to Guston’s.

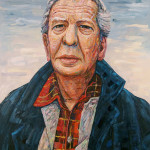

Many of the pieces reference him directly, using his wry humor and pictorial language as a kind of didactic tool. Some of this work, however, is too much Guston affect—a desire to pay tribute to the artist that comes of as a bit cultish, a creative desperation that is part of a larger problem of stylistic imitation and niche-digging in contemporary painting. A genuinely poignant exception is a portrait of Guston by the late Jon Imber, who studied with him at Boston University in the ‘70s. Guston is portrayed larger than life, a somber, shabby giant. In the context of his recent passing last April, Imber’s inclusion in the show is a generous elegy to both him and his former teacher.

Barnaby Furnas The Flenser, 2012, water dispersed pigments, dye, and acrylic on linen, 40 1/2 x 28 1/8 inches. Image courtesy of Steven Zevitas Gallery

Some of the most interesting works hint at Guston’s approach to artmaking without direct reference. Barnaby Furnas’ The Flenser, in sweeping hardlined acrylic washes and splatters of dye, shows a ricocheting arc of jutting arms thrusting long wooden poles into a grey field at the bottom of the canvas. Flensing is an antiquated term for stripping the skin and blubber from a whale. Drenched in sprays of red pigment, the activity on the canvas calls to mind the act of painting as much as it does the ugly work referenced in the title. Here an orange pipe and top hat floating amidst the clamor stand in for the cigarette and hood of Guston’s alter ego that he depicted in later works like The Studio. Whaling is a recurring theme in Furnas’ work, and an appropriate metaphor for the insurmountable problem of painting. Furnas shares a corner with Josephine Halvorson, whose quiet, sensitive studies of grates, doors, and other everyday objects have an earnest, slightly cartoonish animus and a subtle yet physical presence. Viewed together, Furnas’ frenzied violence and Halvorson’s muffled intimacy create a tension that is familiar within Guston’s work, to quote Robert Storr, in the "combined boldness and subtlety"1 of his paintings that perplexed critics and audiences throughout his life.

Remarking on Jasper John’s Flag paintings and de Kooning’s Woman, Clement Greenberg coined the term "homeless representation," wherein the suggestion of a representational image is used to describe a partial space in a work that is still, by virtue of its goals, abstract. We’ve moved beyond such clearly defined binaries and the need for critical categorization, but this description, originally used in the negative, has productive potential in regards to some of the most exciting developments in contemporary painting.

"Everything that usually serves representation and illusion is left to serve nothing but itself, that is, abstraction; while everything that usually serves the abstract or decorative—flatness, bare outlines, all-over or symmetrical design—is put to the service of representation."2 This particular quote from Greenberg has been trotted out in press releases and exhibition reviews throughout the last few years. It seems an appropriate descriptor for the reconsideration of New Image Painting, a loose movement articulated in the late ‘70s and recently reinvoked through exhibitions at Zach Feuer and Shane Campbell Gallery, among others. The Guston Effect continues this exploration, widening the circle to include a diversity of established and emerging painters while providing further historical context.

But why this tug toward the messy, bodily, naïve image in the present moment? Much of the reason artists have repeatedly turned to Guston, to use Robert Storr’s excellent distillation, is "the resulting paradox—of being at once an avant-garde Old Master and a perennial beacon for emerging or reemerging talents," which led to his "anomalous historical status from which [he]both suffered and benefited most of his career."3

Guston abandoned the New York scene and its ideologies during the years of his greatest work, leaving the center for the margins geographically and stylistically. At a moment when artists are pushed out of their studios by exploding rents, student debt grows ever more crippling, and headlines focus on an art market that is barely recognizable territory to most, it isn’t surprising that Guston’s gesture of refusal and the sincere, difficult sorting-out that followed in his late work would be a model to painters today. As the market trend in painting favors non-compositional process abstraction (somewhat reductively classified as Zombie Formalism), the return to New Image Painting or Bad Painting or simply the art of making pictures becomes a radical refusal of the passive blankness of art made as an easy commodity.

The response of many artists in the show is to produce a kind of self-conscious, self-imposed marginality. A lot of the work on view is simply painted in a Guston palette, or with Guston shapes, or are literally tribute paintings, but artists like Katherine Bradford, Amy Sillman, and Jackie Gendel are fully committing themselves to teasing out the possibilities of personal narrative and self-exploration lingering in figurative painting, while maintaining a love for the materiality of paint. In this they have developed an authentic and complex connection to Guston and are continuing his legacy. Purity is nice for those with the privilege of emptiness, but painting will always have a place of refuge for those with the need to tell their stories.

A single lithograph by Guston from 1980 hangs near the entrance to the gallery, anchoring the show conceptually. The Sea features Guston’s swollen, Cylopean heads huddled in a mass and bobbing aimlessly on choppy waves, the land sloping just out of reach in a line that skitters up the right edge of the picture. One of the heads is, of course, smoking. Guston’s last works, made between his near-fatal heart attack in 1979 and his death in 1980, depict these monstrous heads, usually solitary, rolling through a stark landscape of shattered objects, collecting debris and injury as they hobble along under an empty sky. But instead of the isolation and thanatophobia depicted in many of the final works, this is a picture of collective anxiety and a fitting choice for this show. There’s a lot of difference in the artists on view here, but they together share in Guston’s now decades-old despair at the loss of the meaningful image in contemporary culture, and are, in spite of starting from a place of futility, working nonetheless to try and restore it. The struggle is alive—physical, awkward and necessary.

The Guston Effect is on view at the Steven Zevitas Gallery (450 Harrison Ave. #47, Boston) through August 15.

[2] Clement Greenberg, "After Abstract Expressionism," originally appeared in Art International, October 1962

[3] Robert Storr, preface to Go Figure! New Perspectives on Guston, New York Review Books, 2015

- Philip Guston Sea, 1980, lithograph, 30.5 x 40.5 inches. Image courtesy of Steven Zevitas Gallery

- Installation shot of The Guston Effect courtesy of the author

- Richard Aldrich Bonnard, 2009, oil and wax on muslin, 14 x 11 inches. Image courtesy of Steven Zevitas Gallery

- Katherine Bradford Boxing Star, 2015, acrylic on canvas, 9 x 12 inches. Image courtesy of Steven Zevitas Gallery

- Jackie Gendel Twilight of the Idyll, 2012, oil on canvas over panel, 24 x 30 inches. Image courtesy of Steven Zevitas Gallery

- Jon Imber Portrait of Philip Guston, 2012, oil on canvas, 66 x 54 inches. Image courtesy of Steven Zevitas Gallery

- Dana Schutz Swim Smoke Cry, gouache on paper, 30 x 33.25 inches (framed). Image courtesy of Steven Zevitas Gallery