In 1974, at the eve of the national bicentennial, the deCordova Sculpture Park and Museum—then known as the deCordova Museum—organized a major survey of New England buildings completed between 1963 and November 10, 1974, the exhibition’s opening. With New Architecture in New England, "no such exhibition had ever been undertaken, and because the exhibition was the first major survey, it seemed important to publish a catalogue which was more informative than the conventional exhibition catalogue," wrote Frederick P Walkey, the exhibition’s co-curator and deCordova Museum’s executive director in the catalogue’s forward.

Made possible through grants from the National Endowment for the Arts and Design Research International—then at the forefront of bringing modern design into American homes—both the catalogue and exhibition concerned themselves with reaching as broad of an audience as possible. Walkey observes in the forward, that the title could have been "’Architecture as Art,’…for the criteria used in selecting the buildings to be included were subjective and are the same kind of criteria one would use in judging the quality of paintings or sculpture." The buildings selected for the exhibition were chosen for their artistic qualities rather than for their engineering or building techniques. Of the fifty-two buildings selected, the oldest is just shy of turning fifty years old; a milestone achievement for buildings of this era. Celebrations are underway to mark the fiftieth anniversary of Le Corbusier’s only building in North America and the exhibition’s starting point: The Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts at Harvard University.

In 1965, the influential Boston architect Joan E. Goody, laying the foundation for deCordova’s exhibition and catalogue, published one of the first surveys of modern architecture in the city titled New Architecture in Boston. In this early study, Goody highlighted recent outstanding public and private works and notes in the introduction that "..the mid-twentieth century is writing its chapter in the history of Boston architecture, and some of it is as deserving of study as anything in the past."

Not every important building built between 1963-1974 was selected. The buildings that were excluded from the exhibition or catalogue were private residences, apartment houses and public housing projects, buildings which for the most part, were not accessible by the public. The underlying criteria used for the exhibition is derived from the modern movement in that a "building’s appearance must in some ways reflect its true conditions." Louis Kahn’s Library at Phillips Exeter Academy, John Johansen’s Goddard Library at Clark University, Kallmann, McKinnell & Knowles’ Boston City Hall, Skidmore, Owings & Merrill’s Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University and other buildings included in the exhibition moved "toward a visually coherent environment…without the loss of integrity, originality, or expressive force on the part of the individual structure."

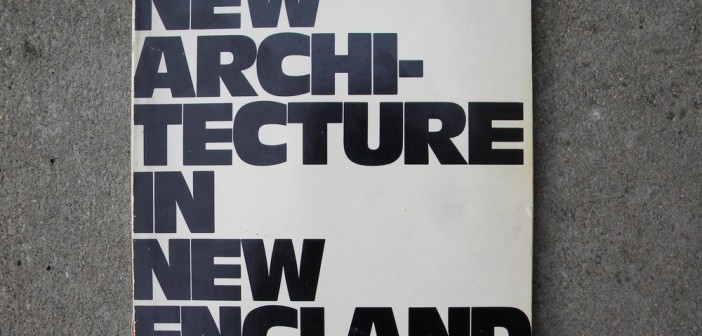

The catalogue was designed by William Thauer and printed at The Nimrod Press, Boston. The title, executed in IBM Univers, a large typeface designed by Swiss typeface designer Adrian Frutiger fills the entire cover. The typeface is as bold and expressive as the buildings in the catalogue are and both beg for one’s attention. The layout follows the conventions of an architectural guidebook, with buildings organized alphabetically by architect. Each building is also listed numerically, keyed to maps at the back of the catalogue.

A full page spread is given to each building—on the left a building’s identification—name, location, materials, site, scale, interior organization, aesthetics and architect are all discussed. On the right, stark black-and-white full page photographs made by some of the best known architectural photographers of our time: Ezra Stoller, Steve Rosenthal, Bruce Fenton and others; invite readers to look deeper into the expressive characteristics of the contemporary architecture being built in New England.

The catalogue includes a twenty-two page, fully illustrated introductory essay by exhibition co-curator Eva Jacob. In this essay, Ms. Jacob provides a concise history of the roots of modern architecture in America—tracing it to the works of its four major creators: Frank Lloyd Wright, Walter Gropius, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, and Le Corbusier. With the advent of new materials like iron, steel, and reinforced concrete and new needs for buildings, the period covered in the catalogue produced some of the "best public buildings built in New England." While most of the buildings could be considered ‘brutalist’ today the term itself does not appear in the catalogue, but rather ‘beton brut’ does and only once.

In recounting how the exhibition and the catalogue came to fruition, Frederick P. Walkey noted that "whether we have succeeded or not time alone will tell. But we hope that this book will stimulate public interest and awareness of the many extraordinary buildings which have been built in the New England area." What this catalogue and exhibition achieved was break away from tradition. It painted a bold, audacious and Heroic portrait of the New England architecture much maligned today; architecture’s ugly ducklings so to speak. If architecture is the least understood of all the arts, New Architecture in New England has made some of the least understood buildings of our time, a bit more accessible today. I for one, have found this catalogue to be a tremendous influence in how I perceive and experience the reinforced concrete buildings rooted in the New England landscape. It has made it easier for me to introduce ‘brutalist’ buildings to individuals with very little or no exposure to the development of modern architecture in Boston and North America.

- Dormitories, Colby College, Waterville, Maine, 1966—68. Ezra Stoller.

- Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, New Haven, CT, 1963. Ezra Stoller.