Yet we still treat this hugely influential region like an imbecile trying to parse Shakespeare or what it often was and at times still remains, left behind while the rest of the world charged forward into the late-twentieth century. And in those choice moments when we don’t, we focus all of our attention on exactly those things I’ve just mentioned: the music, the food, and the literature.

Why not the art?

In an effort to remedy this oblivion, I would like to address the work of three contemporary Memphis artists: Greely Myatt, Dwayne Butcher, and Tad Lauritzen Wright. Though their work is quite different materially, these three share what I would like to convince everyone to call The New Southern Vernacular. The already-extant term Southern Vernacular has been thrown about without much criticality and is usually applied to one of two disparate practices: architecture, generally of the antebellum brick and white pillared-porch sort, and the indigenous linguistics of writers such as the grammatically challenged William Faulkner and the grandly histrionic Margaret Mitchell. What we are left with is a sloppily amorphous aesthetic, partly visual and partly verbal, inherently local and inevitably seen as quaint and nostalgic, though not without the touch of condescension with which the South is often met.

This meaninglessness is precisely why such a framework needs revision. As true as it may be that seersucker and sweet tea are often the name of the game, today’s South, the new New South, isn’t the shortsighted backwater we presume it to be. Neither is its art. Instead we find a region of the country pivoting between its often-shameful legacy and a new identity, as proximate with the international art world as with the cotton fields of the Delta. Simply put, there is more to art in the South than spending a few days at Art Basel Miami, and many of those elements that are specific to the South suit it best for entry into the dialogues and discourses of contemporary art.

Greely Myatt, born 1952 in Mississippi, is best known for his work with empty speech balloons, sourced from comic strips and drawn, sculpted, or excised, begging the viewer to insert some kind of external narrative into the work. And though I’m sure he’d object to my putting it this way, there is no way to avoid seeing this as a Barthesian invitation, a kind of game wherein Myatt is not only spoken for but about, a sly prompt to have us inhabit the Southern Other, if only to let us expose our own prejudices.

An appropriative polyglot, he has also absorbed the language and forms of quilting. The quilts are often made of metal scavenged from old road signs, calling upon his childhood growing up in Mississippi. Their flattened patterning merges the old southern vernacular with the language of mid-century American Modernism, transliterating the codes of their originary feminine domestic into a kind of post-Greenbergian geometric opticality, all the more knowing when hung from metal frames like industrial laundry or, more recently, fused together into something of a flattened David Smith, thus reigniting, certainly knowingly perhaps comically, the high Modernist debates of dimensionality, narrativity, and derivation.

This is the New Southern Vernacular, a kind of globalized local, or localized global, shuttling amongst the self-reflexivity and meta-linguistics of postmodernity, the supposed authenticity of personal narrative, deceptive self-deprecation, and a wicked, moonshine-soaked laugh at our expense.

Dwayne Butcher’s work—not unsurprisingly given that he was once Myatt’s student—shares many of these same tactics. Butcher’s earliest work was regulated by a set of conditions, primarily formal. While one might see this as a young artist looking for a means of creating a stable personal language, and despite the employment of these conditions "to exclude any self-reference to avoid being labeled as some overweight hillbilly from Arkansas," one might argue contrarily that this sublimation of the Southern self has resulted in the opposite. Butcher’s work quickly migrated from a hard, formal abstraction—albeit one with the same kind of faux gesturalism found in Rauschenberg’s Factum paintings—to a more self-performative utterance. In recent years, Butcher has begun making films in which he performs mundane, repetitive acts linked to the cultural stereotypes that have long plagued the Southern self. Partagas, a 2008 single-channel video, sees Butcher sitting in the flooded bed of his pickup, smoking cigars and drinking a six-pack of cheap beer, the emptied cans casually thrown into the water to float alongside his mildly corpulent self. Frontal and centered, like Christ in the Last Supper, Butcher positions himself antagonistically, challenging his audience to judge him, to dismiss him as nothing less than the drunken redneck you know you are when you use your pick-up as a pool. Another dual-channel video from that year, Fat Bastard, continues this self-mockery, with Butcher consuming a small mountain of chicken wings on the left while he simultaneously drains a few dozen beers on the right. This gratuitous gluttony continues in 2010’s Binge, which sees Butcher replaced by his audience, a few dozen of whom are filmed chugging cups of beer. The drunken redneck becomes a costume, a role not only played by those Butcher is able to entice into participation, but available to us all as a performative identity. Whereas Greely Myatt mined his own history to extract motivation, Butcher moves this one step further, asking us all to take part. Not simply an invitation to put words into the artist’s mouth, Butcher’s films culminate in an invitation to assume the role of the artist, not just to see the hillbilly, but to be the hillbilly.

Butcher’s work, too, spans a variety of media and dispositions. His 2009 suite of sandwich boards installed on the sidewalks of Memphis’s South Main Arts District barely lasted the night of their exhibition before being stolen, damaged, and in one case used as a skate ramp. Continuing the color field with the "drips" format of his earliest paintings, in another reconfiguration of high Modernist languages, these were displayed anonymously. Except, of course, to those who already knew his signature style. Their merger of the public address of the sandwich board advertisement with the more hermetic language of abstraction speak to the conflicted nature of his work, in turn openly confessional and cooly detached, never quite decided about their own sincerity. It’s an odd combination of the existential catharsis of Abstract Expressionism and the stone-faced put-on of Warhol. Or, perhaps better put, the way that you’re supposed to smile politely at church to the same people you gossiped about at the club the night before.

Later works, such as the 2011 installation It is Fun Being Me and his paintings from the past few years integrate text into these works, often meditating on the difficulty of establishing oneself as an artist and intellectual from a location as peripheral as the American South. This meta-critique of the regional elitism of the art world is enunciated in pithy phrases, somewhere between the detached authority of Holzer’s Truisms and the nonsensical ramblings of an uncle drunk and combative at the end of a family holiday:

There is a story in everyone.

I look all hot and French.

I like whoever likes me.

An adorable mischievous little fat boy.

I read Playboy for the articles.

Even the goth kids think you’re a poser.

The premier artist of the South.

I get paid to say things like this.

I am not sure, but optimistic.

Dear Artist, Sorry, but your best is still pretty bad.

It is, of course, impossible to tell when he’s kidding, when he’s playing the role of Dwayne Butcher the fat redneck, or when he’s playing the role of Dwayne Butcher the fat meta-redneck artist, if the two are even separable. In this, we return to the crux of the problem that has continued to plague the South: whether any of it is even real anymore. If what is seen as real by others is a projection, internalized by real Southerners as both expectation and condemnation, to be used by the wily against those that would be so quickly dismissive.

The third member of this group of artists—though to expect them to behave as a coherent group is perhaps asking too much—is Tad Lauritzen Wright. Wright, who came to Memphis from Texas, after spells in Nebraska, New Mexico, Hungary, and Oregon, certainly suits the art world’s increasingly peripatetic behaviors. Certainly, the Republic of Texas is a much different geo-cultural entity than the Mississippi Delta, which legend claims begins in the lobby of Memphis’s Peabody Hotel, but this is an important point in this discussion of regionalism in our presumably post-national, globalized, interwebbed art world.

What is the point of discussing the New Southern Vernacular in relation to an artist such as Wright who, though his most recent show Garden and Gun at Memphis’s David Lusk Gallery takes its title from a stalwart of Southern literature, the self-proclaimed "Soul of the South," creates bodies of work that do not belie any particular geographic identity? Granted, Wright’s work does have a certain homely, naive quality that is often associated with the untrained, quote-unquote Outsider Artist, a dangerous taxonomy that rarely avoids some condescension and often invokes tin-foil hats and intergalactic communication. I would argue, rather, that his work taps more directly into the terrain crossed by Art Brut and Homo Ludens, a coy self-aware playfulness, simultaneously endearing, iconoclastic, and ridiculous. The work, with its gratuitous, runny impasto and tweaky post-post-ironic tone has been called Southern Casualism, a term that I cannot help but hate because it not only ghettoizes his work geographically, making it subservient to a more credible non-Southern kind of casualism, but also because it undermines the work’s sharp criticality.1

It is exactly this that makes the New Southern Vernacular uniquely interesting. If it is a style, it is inherently heterogeneous and thus disruptive of its own integrity. If it denotes some kind of geographical allegiance, it is inadequate to describe artists who show internationally and draw upon influences and ideas devised and dispersed globally. Given the historical depth of some of its tactics—identity construction, appropriation, a certain meta-anthropological commentary, humor—its newness is utterly disingenuous. And these very tactics certainly move it closer to International Art English than anything that qualifies as a vernacular.

Where I would argue that this term gains its value is not in any descriptive function or acuity, but as the nomenclature for a certain methodology or tactical perspective, for artists who have, of others’ accord, been forced to contend with frameworks and presuppositions that may or may not actually or accurately explain their lives, careers, and artistic production. The New Southern Vernacular, if I am to explain it at all, wants to explode itself from within. It wants to take what might be seen as any Southern Vernacular—seen, more often than not, as such by outsiders, nostalgics, and the obsolete—and point to its congruence with any regional language. Certainly, it’s Southern, but perhaps only by happenstance or zip code. If I hadn’t mentioned it, it might not have been an issue.

Perhaps I’m the problem. Or perhaps we are all the problem. That is, we the critics who make our bread putting terms to things that may not want them, binding together unlike objects because it suits some parasitic taxonomic instinct that we’ve taken as the natural order since the hierarchy of genres made it such that we feel compelled to box things up and tie them with a bow.

Perhaps we should do something that this Yankee learned to do whilst living amongst these artists. Be quiet and listen. The stories they tell do not need our translation or completion, and to assume that they do is the exact kind of condescending and patronizing behaviors that these same artist have had to endure simply because they come from a place that we assume to be different, lesser.

Perhaps that’s the value of the New Southern Vernacular. If we listen to it closely and quietly, we may just learn that it is an American vernacular, a global vernacular, everyone’s vernacular.

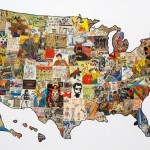

- Tad Lauritzen Wright Handsome Western States , 2009 Mixed media collage on canvas 48 in. x 72 in

- Tad Lauritzen Wright Goodnight Sweetheart, mixed media on canvas, 2012,

- Tad Lauritzen Wright Forgeting Where I’m From, mixed media on canvas, 2012.

- Greely Myatt, Zipcode, alum signs, aluminum, and steel, 2012.

- Greely Myatt, Verb, Steel, 2012.

- Greely Myatt, Left with this Myth, aluminum, reclaimed wood and metal signs, florescent light, 2012.

- Dwayne Butcher, Sandwich Boards , Acrylic on Wood, 2008.

- Dwayne Butcher , Partagas, Single Channel Video, 2008.

[1] The reference is to the New Casualist painters.

In an effort at full disclosure, it must be noted that the writer has some personal history with those artists discussed herein, mostly during his tenure as Faculty at the Memphis College of Art. This investigation has been limited to these three artists for reasons of both cohesion and efficiency. There are any number of other artists who might have been added, including Susan Maakestad and Lester J. Merriweather. If one were to treat the South as a diaspora, an argument might be made for an even more diverse group.