your eyes little thing go to sleep little fuck

feel my hand on your warm forehead

It's cold isn't it? Ice cold.

Dream of something real sweet

for mommy

Mommy likes sweet things

Dream of merry-go-rounds and

cotton candy

Mommy's hand got all warm

resting on your tiny head

See, look at mommy's hand

It got all warm now

You're running a slight fever

Mommy will get you some

water

And you're running a slight

fever

Little fuck don't have to go to

school tomorrow

but no playing in the yard

Someone could see you

And I'll be an unfit mommy

You'll have to stay in all day

but now, dream of the prettiest

flower for mommy

I'll make you oatmeal first thing

And you could tell me the color

of the -

prettiest flower.

Canyon Cinema Catalog description for the film WARM BROTH by Tom Rhoads (1988)

Luther Price's films have been disturbing comfortable consciousnesses for over two decades. A native of Boston, Luther attended MassArt in the early 1980's where he developed an abundant body of work as a sculptor and performance artist. While at MassArt, he met Film faculty members Mark LaPore and Saul Levine, who took interest in his work and supported his expansion into Super 8 filmmaking. In 1985, at the age of 23, Luther was invited to participate in an artists' cultural exchange in Nicaragua with a small group of artists from the United States. On the morning of the day they were to return to Boston, he was accidentally shot in the side at close range by his 15-year-old body guard who was cleaning his AK 47. After eleven days in a Nicaraguan hospital, he returned to Boston where his medical records were confiscated, leaving him with a bullet in his hip for several months. Eventually, the bullet was removed and he regained mobility, but the injuries left him with chronic afflictions and a lifelong relationship to pain. This profound connection to anguish carried through to his artistic practice, and he began making Super 8 films that boldly eviscerated the empathetic essence of what was traditionally a "home movie" format. Two decades later, Luther has created more than 200 films that are visceral, poignant and downright beautiful expressions of loss, joy, fear, desire, sadness, recovery and redemption.

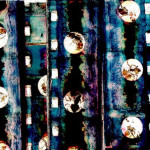

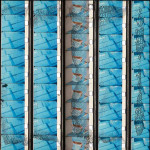

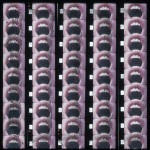

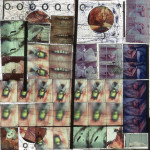

A true "mixed-media" artist, Luther approaches filmmaking like a sculptor, often painting, processing, puncturing, scratching, staining, burning and burying the film to manifest his images. He is extraordinarily organized and frugal with his footage—many of his 16mm films are composed of found footage taken from discarded or donated films, and his recent 35mm glass slides are collaged film fragments rescued from his studio floor. (As Luther's student at MassArt, I was required to collect my discarded film fragments in a plastic baggie for use in my "future projects"). Most of his 200 (plus) films exist only as single-copy originals, though approximately 15 films are available for rent via Canyon Cinema, LightCone, and the Filmmakers Cooperative.

Luther Price has had a hell of a year: In 2012, he was a featured artist in the Whitney Biennial, had solo shows at both LUX in London and the New York Film Festival's Views From the Avant Garde program, and installations of his slides were shown Callicoon Fine Arts in New York and the deCordova Sculpture Park and Museum in Lincoln, MA. Luther will be showing both an installation of handmade slides and film loops at Boston's Studio Soto, opening Saturday, October 13th.

Luther currently resides in a beachside bungalow in Revere that is at once his home, studio, screening room, gallery and sculpture garden and sanctuary. I met with him during a heat wave in July, and we talked about his past, the present, and what is yet to come.

TN: You have had many personas over the years through which you create your work: FAG, Brigk, Tom Rhoads.

LP: Tom Rhoads is a good place to start. There were nicknames and other names before that, and the names changed because of situations that might have occurred in my life. I was really only FAG for one night. But then my friends started yelling across the bar "FAG! FAG!" and I was like, "this isn't working". Brigk was a persona coming out of my injuries in Nicaragua, and the end of one part of my life that was very sculptural, and moving into film. After my accident, I became very introspective, and I felt I needed to investigate something other than social issues.I needed to really go back into my own self and investigate my own childhood, my past, where I grew up, my roots. I continued to work in a sculptural way. I began to collect objects. I would find a coffee cup in a thrift store that reminded me of a cup my mother used to drink out of, or a lamp, recreating my past, things that came from my era that I could specifically remember using. So it wasn't just about going back and using film to talk about the past, but also using objects. Creating sets and temporary vignettes and things like that, and finding something very physical in the object. I think objects have a lot to talk about. They outlive many of us, and they have a history, an energy. And when I was done with them, I would release them back into the world, and they would go to another home. I used a lot of these types of objects in both WARM BROTH and GREEN.

TN: How did you begin working with found footage?

LP: Many of the found footage films I made in the beginning were an extension of my own history. In the same sense, I am using found footage not as an object, but because of the sense of the past that it represents. I would go through a porno film but I wasn't interested in the cocks and the asses, I was interested in the lamp, or the curtains, or the pillow. The cutaway shot of an object. I am not collecting the objects, but I am using the object in the film to connect to.

TN: Some filmmakers, myself included, have a very hard time working with found footage in a meaningful way. For myself, I find it overwhelming to choose the right place to cut in, where to interrupt the film, where to insert my own decision. How do you approach working with found footage? Where do you begin?

LP: Well its always different. Sometimes the material is going to say something to you. There’s tons of great footage, but you have to respond to it. I let the footage tell me what to do with it. Because of this, I feel that the film is my collaborator, and the film becomes a collaboration. You can't ever push anything. I'll go through something and dissect it for the parts that I respond to and relate to. That's first. I'm sort of matchy-matchy when it comes to films. When I found those two pieces of footage [the two films that are juxtaposed in the film KITTENS GROW UP]I knew right away that they had to be together. Also, the colors worked. And if you look at the film, the same rug that those kittens are on is in that house. There is a lot of matchy-matchy stuff. They work together in an aesthetic way. Many times I will get really involved in color as one of my main aesthetic issues so I'll say "hmm there's a lot of green here" and start collecting different textures of green. So color is many times a major issue for me, a path towards finding something within the structure of the film. Of course, the content becomes a major issue too. I was recently asked "what is more important to you, the aesthetics or the content?". It seems like a hard question to answer, but I answered it pretty quickly: aesthetics, definitely aesthetics. To me, that is what my quest is for, to find a beautiful aesthetic, or if it's not beautiful, an ugly aesthetic, but something that is visceral. The aesthetic of anything is a visceral element that we can all respond to. It becomes a sort of language. Aesthetic can be very raw and visceral. Whether or not you are responding to the way something is structured and cut up or juxtaposed, or it could be color, or the absence of color, all of this stuff becomes a visible, visceral language.

In SORRY HORNS [part of the 16mm found-footage SORRY series of films], I am responding more to the homoerotic element of these guys, lined up, blowing these horns with their sandals, and the short skirts that they have on, the cute legs...It's very fleshy to me, it has a sort of deliverance of flesh about it. Of course it's connected to Jesus and his story, but it has its own sort of homoerotic pillow around it. And there's enough information in there - we all know the story. We all know what they're up to. It's the announcement of Jesus to face his consequences. So we know that. But I'm looking at their legs.

TN: In many of your films there is a very dramatic relationship between sound and image; sound is almost an interruption of the picture. In some cases, you have painted over or scratched-off the existing soundtrack, in other cases you use the sprocket holes of the film strip as the audio. With some of your found footage films, the sound/image relationship is interrupted through the insertion of one film into another.

LP: I write that way too. I use a lot of dot..dot..dots as sort of spacing for the way I talk. I like to use leader in the same way. You will hear the interruption of the sound of the sprockets in-between to shots to emphasize a certain moment. Like in KITTENS GROW UP, when the little girl is looking out the window waiting for her drunken father who has taken her mother out of the house to keep him company at the bar...she's looking out the window, pathetic. So I use the black leader as an explanation for this, for her solitude in a very abstract, constructive way.

I cut things off where they shouldn't be cut off. I do this because it helps to emphasize, or de-emphasize, a certain moment. If you have a certain rhythm going on and all of the sudden you've got this long wait, a long moment where there is just the sound of the film itself, dragging itself through the projector, it builds anticipation in a different way. It gives you space.

TN: In your film SHELLY WINTERS, there is no image at all, just white leader and a soundtrack We hear the voices of both victims and perpetrators of domestic violence, telling their stories, but there is no image.

LP: That's a very sad film. It's a struggle for survival. I get emotional about that one. And that film was made in Quincy, so we know the accent, there is an indigenous thing about that film. One of her only escapes was to go to Dunkin Donuts. Dunkin Donuts has been part of my life for as long as I can remember. So you feel closer to her pain because she feels almost like a relative, or like your neighbor.

In that film, the absence of image creates an emptiness, a vastness. It becomes its own vast ocean of emptiness. It almost becomes a metaphor within the image itself... for her pain... that she is alone in this ocean of emptiness, and the fact that we are left with no color, no movement, no image, everything is left in the solitude of your own self. You start to understand how pain can look like nothing. Pain can be a vast hole of space that is just there.

TN: Your films are very powerful not only because of your technique with color, motion, sound, and picture, but also because they have the ability to procure a profound empathetic moment. I am often surprised at how emotional I get when I see one of your films, especially the more recent ones. Do you think your work has become more empathetic over time?

LP: Once I left my own direct autobiographical path, which I came to a conclusion with once I decided I didn't need to focus on myself so directly. I kind of ran out of family to be honest. I didn't want to talk about them anymore. I thought "You have a choice, you can continue on this path talking about your own pain and self-pity, or move on". I couldn't stay there. I would rather not make films than stay there. So I took a break for a while. I felt like no matter what I touched it was just going to be about ME. Not that I resorted to found footage, but I found that I could still talk about some of these issues but they won't be directly about me. Like with the BISCUITS [a series of films using footage depicting the elderly]- I found a sadness about these poor people's lives, and I got to know them in a sense. Just because they were stuck in film forever doesn't mean that I couldn't have feelings for them. And I didn't have to talk about my own personal pain directly anymore. And so I was able to move on.I also think that in the extreme use of repetition in the BISCUITS (because I had 13 prints of the same film) reinforces the relentlessness of it...it doesn't go away...it's a continuation, this tragic loop, it goes on and on and on...I am able to say yes, I've had pain, but other people have too. The repetition reinforces the fact that this is the way its gonna be forever and ever and ever. At the same time...maybe not. Even when you are going through bad times, you can still have that one good day, that one good memory.

TN: Your 1989 film SODOM was an underground "hit", and made a huge impact on the experimental film scene for many years. It is a very visceral, dark and carnal film that references ritual, religion, sexual deviance, and lust. Luther Price is still widely known for this film. How do you feel about that?

LP: Thank God I'm not known for just that film anymore. It was from a different time, it was from 1989. People had a whole different outlook on all of that stuff. It really is a different world now. And who wants to be known for just one thing? That film was made two decades ago, and I was doing different work than I am now. I feel like the work I do now can be more accessible. It can be light, it can be heavy, but it doesn't have to BE ABOUT SOMETHING. Because of SODOM I became know as this gritty, badass, gay filmmaker and...I'm not. Yeah, I'm gay, I like to look at guy's asses, but SODOM is not a pornographic film to me. It's just very fleshy and visceral, and it talks about a story.

TN: Do you feel that your work has a sense of humor? How do you feel when people laugh?

LP: With KITTENS GROW UP, people laugh at first. But then it sort of creeps up on them that this isn't all funny. But no matter how serious the film is, I'm not going to get mad at anyone for laughing. It's like hitting your funny bone. You sense that something just isn't quite right. It's a tingle in your body and you don't know what to do with it, so you laugh.

TN: You are a very prolific filmmaker. You are working across so many mediums in a very productive way. I would like to talk about your practice. What is it like? Do you get up every day and go to your studio? How do you remain so productive?

LP: My work ethic is always different. Right now, I don't have a direct schedule, so I wait for that urge to come in. I have taken a break for about a week now, and it feels like forever. Because I literally had to switch over and think about other things, respond to other things and not put them off in order to prepare for other things. Recently I have been focusing on making the slides. And I'm glad that I did that. My goal was to pick that up early this summer and have it completed by the fall. That didn't happen, but I'm patient, I'm not getting down on myself because I redirected myself to make the work that we saw at the deCordova, which I am very happy with. It's very different from the Whitney slides. So I am not stagnant, I am taking what I'm getting from making the slides and dealing with a singular static image and hopefully going to bring that into film when it moves, in a different way.

TN: You have had a series of health issues that you are still dealing with on a regular basis. How do you remain motivated when dealing with chronic pain? Is filmmaking cathartic? Does it motivate you through the pain?

LP: You know, I have been sick for a while. And filmmaking itself is painful, sitting over a bench with your head facing down, staring through a loupe for hours at a time, it gets painful after a while. It's not an excuse, but you have to learn to deal with it. I would rather not work than put this bad physical energy that I'm having into the work. I try not to work when I'm in that much pain... I spend a lot of time at home because this is my studio and my house. My favorite way to work is to work on several pieces at once. So I'd work maybe three hours on one film, and get it to a point where I could just put it down for the day. And I would think about it later, or wait for something to come to me. I would put one film away and then reach for the next film, but they were all speaking the same language, or would eventually become part of a body of work. And that way, five or six films would be finished at the same time, because you are giving them equal attention. I still don't like to work on just one film at a time. I like to work in chapters. Right now I excited about some of the things I am coming back to that has been on shelves. Some of it might be finished, some of it I might need to reconstruct. A good grouping of these current chapter films will be called "An After School Special", they all have this little narrative about them.

In one of them there is this little old guy feeling sorry for himself, I think it's from an old Police TV show from the 70's - stuff I would watch with my grandmother when I was growing up. This old guy is feeling sorry for himself, sitting all alone, so I called it "Old Man Luther". That's a chapter. It doesn't always have to be rigorously dealing with the material in a visceral way, sometimes it can be very lethargic. Sometimes you are dealing with the footage in a lethargic way, and that's saying something.

TN: I am very excited about the handmade slides that you have been working on.

LP: I'm interested to keep working with the slides, because they are going in a different direction, each batch that I make. They aren't repeating themselves. I'm dealing with issues like liquid and movement within the slide. How can this image become something that changes within itself? So I'm using lots of olive oil, things that won't dry up and making these little vignettes with cut-up pieces of film. Think of it like a snow globe that you shake up, it constantly changes. There are different ways of working. So I don't want to stop working in this way now, I'm enjoying it.

- ……#9 ‘oxcidation….blue’………2012…….

- …”Bricks Pain’……..2005…….

- ………..’Fibroid Family Kitchen”…..2005…….

- ………”Meat Mouth’………..2005…..

- ………”I eat you maggot meat”………2005………..

- ….”#9…….”Pearl Swirl”…2012…….