Has anyone else noticed that Art Basel Miami Beach seems to have produced its own seasonal affective disorder? Reading Patricia Cohen’s "An Art World Gather, Divided by Money", a roundup of the usual art world suspects and their art-fair discontents in the New York Times gave me an early Groundhog Day feeling. Every year, around this time, the art critics start piling kindling on that yule log I like to think of as the "Kvetch Before Christmas"—the annual lamentation about how OPM (Other People’s Money) is bad for art.

Cohen writes that "prominent art writers and critics, including Sarah Thornton, Felix Salmon, Will Gompertz and Dave Hickey, have been … arguing that the staggering sums of money being spent on works are distorting judgments about art and undermining its long-term cultural significance," referring to Sarah Thornton’ peevish ‘Top 10 reasons not to report on the art market.’ Thornton’s reason #1 is "It gives too much exposure to artists who attain high prices. You end up writing about paintings by white American men more than is warranted. You appear to endorse ... artists that you consider historically irrelevant because the day’s financial news dictates the shape of your narrative."

Why does Thornton feel she must endorse artists she dislikes? Financial analysts report market news while simultaneously critiquing bullish stock picks they believe to be overvalued—that’s part of their job. As a champion of the brilliant artists coming out of Boston, I challenge Thornton, Saltz and the others to put their money where their mouths are. They have the columns which command national and international attention—why don’t they use their bully-pulpits to bring a spotlight to the artists who aren’t pulling the big prices instead of just complaining about monied folk who pay too much for the art they buy at fairs?

Cohen reports that, "Many in the art world worry that even if superpowered collectors play a useful role in the market, they also exert a disproportionate influence on it. Their particular tastes ... can cause a middling artist to be elevated and a great one to be neglected." This quaint use of ‘middling’ makes me think of some turn-of-the-century novel depicting the hapless cultural failings of the Bourgeois. (Thomas Mann’s Buddenbrooks is the one I had in mind.)

Even Jerry Saltz, of Bravo TV’s "Work of Art: The Next Great Artist" fame, posted recently in one of his enjoyable, unfiltered Facebook posts about contemporary art auctions, "Always people walk out of auction[s]nattering utter nonsense. ‘It's a smart market.’ Or ‘People are really going after quality.’ Forget that none of this has anything to do with ‘quality’ or being ‘smart.’ These spectacles now happen dozens of times a year ... none of it has anything whatsoever to do with art. Let alone ‘quality’."

In the face of Art Basel Miami Beach and the contemporary auction market, it seems that normally level-headed art critics feel the need to defend their hegemony as the arbiters of ‘quality’ by resorting to what would be called race-baiting, except that the locus is Cohen’s "art world ... divided by money" rather than race.

It is astonishing to me that in the 21st century some critics feel the need to to shore up the value of their hard-earned cultural capital in the face of vulgar economic capital (and the public fascination with it) by reverting to a 19th century framework of merchant class vs. learned class, implying an inverse relation between a collector’s ability to pay high prices and their ability to discern ‘quality’ and ‘cultural significance.’

I agree that there is entirely too much ink spilled about art market prices and not enough candid conversation about other ways of assessing ‘value’ in art. I was reminded of this recently at the successful opening night of a friend’s comedy (shameless plug here for Jon Kolvanbach’s farce about the life of an actor currently playing at the Merrimack Repertory Theater.) I can say with certainty that it was a successful opening night because there was laughter at all the right places. This made me a little jealous of the performing arts, in which the benchmark for success is a lot easier to find. I spend a lot of time critiquing the ‘fine arts’ and I can tell you that assessing ‘success’ without resorting to market values can be so subjective it could be the subject of its own farce. The public likes to know the score—they want to know who’s winning—and prices are a lot easier to grab on to than Benjamin Buchloh’s dense prose about the paintings of Gerhard Richter, for example. But where does this leave the ‘fine art’ critics?

It's really the old Bourdieu ‘Field of Cultural Production’ chestnut: the struggle for dominance in the ‘field of cultural production’ between the broke critics and the art collectors with deep pockets, over whom should be the arbiter of good taste. It rattles many critics when (rich) art collectors have more influence than (poor) art critics over what is ‘historically relevant’ by virtue of the market and its media.

Sarah Thornton says, "Money talks loudly and easily drowns out other meanings. The general public’s interest in money takes art stories out of the art section and into the front pages of newspapers … but maybe art is better served when the articles about it are at the back." In other words, perhaps we should keep the public from focusing on bad art by not putting articles about the art market on the front page. But really, what is so bad about educating the public about the value of contemporary art, even if you think it is the wrong sort of art? Isn’t that better than telling them again about the enormous salaries of professional athletes? Leo Castelli once said, "There is a very important moral function carried out by high art prices, by the fact that this makes art valuable. A society can preserve only things that are valuable."

Which leads me to my final bone to pick with the art world professionals who decry the insidious impact of private money on the art world. Cohen quotes art dealer, Magda Baltoyanni, as saying "Galleries run the game now, not the museums." The problem with this statement is that museums have never "run the game." Most major American art museums started as private collections, formed under the advisement of robber-baron art dealers like Bernard Berenson and Joseph Duveen. The earliest curators of The National Gallery and the Metropolitan Museum of Art) were the art dealers who shaped the collections of Andrew Carnegie, John Taylor Johnston, the Havemeyers, and Robert Lehman to name just a few. I would opine that this mostly symbiotic relationship between collectors, dealers and museums is not an entirely bad thing. Can you imagine the kind of art we would have if all museums were truly "accountable to the public"—that means both the red and the blue state—as Occupy Museums proposes?

Perhaps my location in Boston, with its respectable but skeletal art market is making me curmudgeonly. But listening to these complaints about the harmful distractions of the ultra-high-net-worth art collectors from here is like listening to the CEO of J.P. Morgan complain about how to spend his $42 million bonus while I eat ramen for dinner again.

- Tavares Strachan at Anthony Meier Fine Arts Art Basel Miami Beach, 2012 Photo: Sarah Grace Sulistio

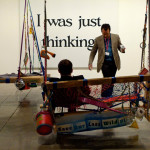

- Art Basel Miami Beach, 2012 Photo: Sarah Grace Sulistio

- Art Basel Miami Beach, 2012 Photo: Sarah Grace Sulistio

- Art Basel Miami Beach, 2012 Photo: Sarah Grace Sulistio

- Art Basel Miami Beach, 2012 Photo: Sarah Grace Sulistio

- Andrew Kreps Gallery Art Basel Miami Beach, 2012 Photo: Sarah Grace Sulistio