Last week that somewhat abstract, somewhat media-hyped notion of a fiscal cliff appeared to have been resolved with the mini-agreement coming from Congressional leaders. Concessions made by both parties produced a marginally equitable deal, though it stopped short of restoring faith in our ability to elect governing officials who can deal with present-day economic realities.

In the lead-up to the deal, non-profit organizations worked overtime to impress the importance of not messing with the charitable contributions tax exemptions. The "American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012" that was passed last Tuesday ultimately has mixed results for NPOs and arts organizations who rely on charitable giving. The good news: The dollar cap that was proposed by Governor Romney and congressional Republicans wasn’t included, nor was the President’s proposal of a 28% tax rate limit on itemized deductions for those earning over $200,000. Further, it reinstated the IRA Charitable Rollover provision which allows tax-free distributions to eligible charities from an IRA held by someone age 70 or older, of up to $100,000 per taxpayer per year. The extension was made retroactive to Jan. 1, 2012 and allows donors to make distributions directly to eligible charities before Feb. 1, 2013 and elect to have such distributions treated as qualified charitable distributions in 2012. (Previous legislation allowing IRA charitable rollover gifts had expired on Jan. 1, 2012.)

Although charitable exemptions remained, the agreement didn’t do so without some changes because also included was the reinstatement of an obscure and little understood Clinton-era provision called the "Pease Amendment." Its impact on charitable giving—and other itemized deductions—is truly minor, much less than the President’s 28% limit or the Republican deduction cap, though it will limit the amount wealthy people can claim for charitable deductions. The Pease Amendment, named after its author former Congressman Donald J. Pease (D-Ohio), reduces the value of deductions for wealthy households by 3% of a taxpayer’s income above a particular threshold ($300,000 for married couples filing jointly, $250,000 for unmarried individuals). This, when taken with the agreement to allow the Bush tax breaks to expire for individuals making $400,000 and families above $450,000 from 35 percent to 39.6 percent, has both local and national non-profit arts organizations worried how it could impact giving to charities in the future.

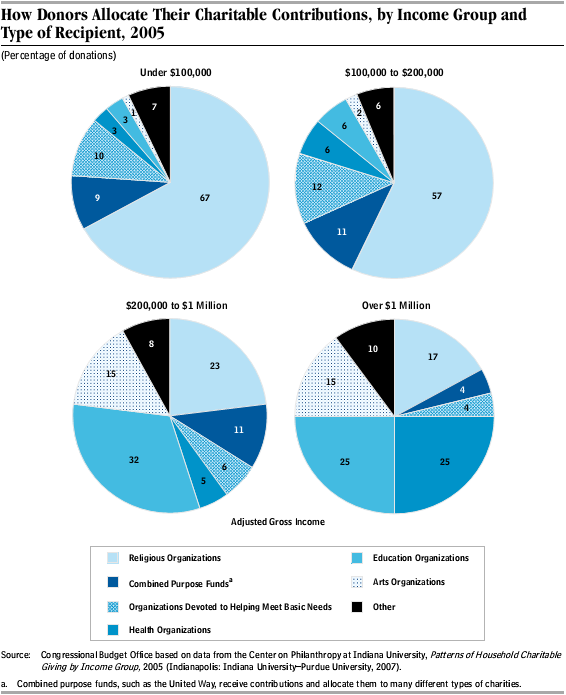

Taking a look at these policies and their potential effect on charitable giving, The Bureau of Business and Economic Research cites the following chart from the Congressional Budget Office which makes it look quite grim for the arts, as wealthier donors make up the largest proportion of donations to the arts:

What isn't discussed, however, is that 2012 already saw record lows in charitable giving, likely due to deflated confidence all-around. Furthermore, many of the policies passed in the fiscal cliff agreement come straight out of the pages of the 90s. The Pease limitation, for example, was instituted in 1990 by the Omnibus Reconciliation Act and stayed in full effect through 2005. During that time, charitable giving increased by 83% when adjusted for inflation. Then again, even though the political structure of the 90s is quite similar to ours today, the economic times are quite different.

With all of that in mind, will Boston-area arts organizations be impacted? It's likely that the largest effects of these policies will be seen at the more prominent institutions—those that derive the majority of their funding from private donors but who can handle whatever drop may occur, as they have already been handling during the recession. Smaller arts organization face a slightly different problem. Alison Hawkins, director of external affairs for the Alliance for Charitable Reform, told the Bureau of National Affairs' Daily Tax Report, "The problem is that charities have been operating under bare bones operations, serving so many more people, that anything that will hurt charitable giving is a problem." And though these policies have the potential to hurt smaller charities, the bigger problem comes from what wasn't addressed in the mini-agreement—namely, the looming "sequestration" cuts.

As a result of the failure of the deficit reduction super-committee to reach an agreement in November of 2011, a $1.2 trillion series of broad-based automatic spending cuts were to begin January 2. Those automatic cuts, known as sequestration, were to be split evenly between defense and discretionary programs including education, transportation and the arts. The fiscal cliff deal, instead of addressing this problem, only postponed the start date for two months. After that, lawmakers will again debate which areas should continue to receive funding and which should have their budgests slashed. For the arts, popular institutions like the National Gallery of Art and the Smithsonian will probably continue to receive support from the government. But "controversial" groups like the National Endowment for the Arts, which has already had its funding cut repeatedly in recent years, may not fare as well. Because of this, these sequestration cuts are what pose the largest threat to smaller arts organizations, many of whom rely on grants from organizations like the NEA to continue operations. As we've already seen so many small Boston arts NPOs go under in the past 5 years, a further reduction to funding could be potentially devastating to the ones who survived the recession and those who they serve. Remembering that may help us when trying to understand and fight against these somewhat abstract economic cuts to groups like the NEA; remembering that these small NPOs have begun to occupy a larger place in our community and that their survival is important to our city as a whole.