Cannibalism "was a nationalist strategy of cultural anti-imperialism, according to which the culture imposed by the First World should be devoured, digested, and recycled according to local needs."

—Film Reference, on Brazil’s Cinema Novo

Speaking with ICA Assistant Curator Anna Stothart, at the opening reception for her first solo museum show in the United States, Brazilian artist Adriana Varejão provided some crucial insights toward understanding the conceptual grounding of her works on view. A name, briefly mentioned during that conversation, which is not listed in any of the publicity or didactic materials surrounding the show, has revealed itself to be a decisive element in the development of Varejão’s dynamic artistic practice.

José Lezama Lima may be best known to North American audiences through his off-camera role "as the gay protagonist’s most important cultural hero"2 from the taboo-breaking Cuban film Fresa y chocolate (Strawberry and Chocolate), which many regard as a milestone in Cuba’s maturing attitude towards the gay community. Lezama Lima’s contributions to the socio-poetic realm were extensive: from reflecting on the American1 cultural identity (mestizaje), to challenging historiography and defining eras imaginarias (imaginary eras)—moments within "intertextual" cultures, which provide for the "potentiality of image creation", presumably with the purpose of creating images of contrapuntal significance—a kind of precursor to Futurism.

As a prolific essayist on the subject, Lezama Lima warned against the inherent impossibility of reconstructing the "truth" of events, of Hegelian causality—and elaborated his Toynbee-esque perspective of history as being typically created (written) by the image, or rather, by cultures which have defined their own unique imaginations of history—imago as history. As Lezama Lima writes: "Historical vision, the counterpoint or tissue bequeathed by the imago, by the image participating in history."3

This preoccupation with historical rupture, productive fabrication and revision is quite present throughout Varejão’s work, which Stothart describes as "confront[ing]this historical aggression by turning colonial imagery back on itself to expose its own fictions and biases."4 In Figura de convite I (Entrance Figure I) (1997) a large oil painting literally welcoming audiences into the show, Varejão grapples with misinformed European assumptions of indigenous Brazilians, colonial-era Portuguese tile arts, and the proverbial Modernist grid.

The life-size central figure of a woman (often cast in Varejão’s own likeness) in the painting is a reimagining of a popular eighteenth century tile genre—traditionally portraits of nobleman in similar postures of welcome throughout Portuguese and Brazilian palaces and gardens. Varejão incorporates the blue and white palette of these decorative surfaces, known as azulejos, to both comment on their imposed ubiquitous nature across Brazilian architecture, as well as the lingering damage dealt by European "travel writers" of this time. One such sixteenth century Flemish printmaker, Theodorus de Bry, "documented" scenes of savage cannibalism amongst the indigenous people without ever having set foot in Brazil. Varejão includes these brutal images, borrowed from de Bry, in the background behind the female figure, in a complex gesture that reads as welcoming and confrontational at the same time.

The Manifesto Antropófago (Anthropophagic, or Cannibalist Manifesto) by Oswald de Andrade (1928)5 is another seminal piece of Latin American literature, which has heavily influenced Varejão’s work. In this case the connection to Varejão being that de Andrade was also Brazilian, has been written about before (along with the debt Lezama Lima owes the older Brazilian modernista), including throughout the museum text for this show.

The brief Manifesto playfully denounces the supremacy of European culture and boasts of Brazil’s ingestion of foreign influence, "as in the rituals of some Pre-Columbian war cultures, not only mixing one cultural form with another, but drawing on a unique contact with unconscious drives that had been more repressed in ‘civilized’ cultures of the de jure colonizers of the past and the de facto colonizers of 1928." In a classic opening line of the piece, de Andrade asserts that the fundamental question for Brazilians is indeed: "Tupi or not tupi"6—that of a relentless créolisation of external influences in order to preserve national identity.

Two decades later, writing in Tropiques from a Martinique in the grips of a nightmarish meta-narrative of occupation in the form of the Nazi-allied Vichy government ("the colonized colonizer"), Suzanne Césaire boldly claimed: "Martinican poetry will be cannibal or it will not be." Thus, Varejão’s fusion of de Andrade’s Cannibalist method with Lezama Lima’s poetic intention of "counter-conquest", as told through a Feminist perspective, has a worthy precedent on the other side of the Caribbean.

The global applications of this de-colonial gesture are hinted at in Varejão’s Mapa de Lopo Homem II (Map of Lopo Homem II) (1992/2004) in which Portuguese cartographer Lopo Homem’s 1519 projection of the world is presented as a three dimensional half-sphere mounted on wood, with a deep, fleshy gash running from Turkey down to Antarctica. This wound, practically amputating Eastern Africa from the Arabian Peninsula, is a gaping one, right in the center of the composition. Smaller, lateral, partly sutured incisions balance out the piece at various other locations on the map, perhaps in an acknowledgement of the devastatingly long reach of the Portuguese colonial arm. Varejão is channeling the aforementioned literary figures and quite literally lacerating history, creating ruptures in the weaver of history, the tissue of history, as Lezama Lima would say: the image.7

In Proposta para uma catequese-Prato (Proposal for a Catechesis-Plate) (2014) and Proposta para uma catequese-Parte II díptico: aparição e relíquias (Proposal for a Catechesis-Part II Diptych: Apparition and Relics) (1993) Varejão’s anthropophagic instincts are acutely honed, deftly framing her compositions with the subtle, yet precise flamboyance of Baroque decorative elements. So-called ornamentation becomes fundamental to this work. Through its juxtaposition with familiar motifs—Varejão’s disembodied hands/legs and Eurocentric scenes of indigenous cannibalism—the pieces provide a scathing critique of Catholic hypocrisy towards indigenous traditions in light of the obvious savagery of Christian practices and their morbid mythologies, such as the cannibalistic "transubstantiation" of the bread and wine for the Eucharist. The provocative contrast is doubly reinforced by Varejão’s titles, which reference Catholic religious education, whose name in Greek appropriately signifies "instruction by word of mouth". Varejão is here engaged in a multilayered process of intentional Baroque recontextualization that necessarily brings us back to the essayist Lezama Lima.

In La curiosidad barroca (The Baroque Curiosity), from his 1957 collection La expresión americana (The American Expression), Lezama Lima put forth a rupturing understanding of the American Baroque as "an art of the counter-conquest." Departing from the established view of the Baroque aesthetic as a political arm of the Catholic Church during the Counter-Reformation, Lezama Lima develops a poetic, anti-historiographic analysis of the fundamental ways in which Baroque art in the Americas, or "el mestizaje barroco", differed from its counterpoint in Europe.

Following Martin Luther’s ultimate "trick or treat", the revolutionary 95 Theses in October 1517 and the subsequent Protestant Reformation of Western Christianity, the Roman Catholic Church, in an effort to reaffirm their power over individuals’ lives on Earth and in Heaven, convened an ecumenical council in Trento and Bologna, Italy, between 1545 and 1563.

This eighteen-year Papal plenary, known as The Council of Trent, sought to "address" well-founded Protestant criticisms of corruption at all levels of the Catholic Church, their absolutist claims regarding interpretation of Scripture, and the veneration of saints and relics (read: body parts). In addition to these, the Council found it necessary to pronounce on the role of the arts in extending the reaffirmation of Catholic doctrinal supremacy—condemned were the nude figures (including the Christ child), the "sober rationality" and the classical pagan elements of the popular Italian maniera of the mid-16th century. Church officials saw Mannerism as an impious and intellectual movement, which lacked appeal or comprehension for the masses. The art of the Counter-Reformation would thus be without superstition, lasciviousness, lustful excitability, or unbecoming disorder8, and it would abound in Catholic expressions of triumph, power, and absolute control, at least in Europe.

While Western Christianity tore itself apart over canons and decrees of salvation, glorified marauders such as Pedro Álvares Cabral and Cristóbal Colón ("Columbus" in English) had already become seasoned professionals in the genocidal colonization of places like Brazil and the Caribbean islands. Inevitably, the proclaimed aesthetic style that would sweep Western and Southern Europe, would also make its way to the American colonies.

Adriana Varejão Eye Witnesses X, Y, and Z (Testemunhas oculares X, Y, e Z), 1997 Oil on canvas, porcelain, photography, silver, glass, and iron Three canvases, each 33 1/2 x 27 5/8 inches; installation78 3/4 x 98 1/2 inches overall Collection of Frances Reynolds

For Lezama Lima, European Baroque was characterized by an austere adherence to the principles of "accumulation without tension and asymmetry without plutonism".9 Amongst the American Baroque practitioners, Lezama Lima describes tension as the mestizx juxtaposition between indigenous, African and European elements common amongst the American Baroque practitioners. He provides this example: the Bolivian "indio" Kondori, attributed artist of the awe-inspiring doorway of the church San Lorenzo de Carangas in Potosí, imbued their Christian paean with a revolutionary indiátide, an Incan princess. Lezama Lima writes: "that figure, the temerity of the stone obliged to elect symbols, has incised the elements so that the Incan princess can bask in the courtship of our praise and reverences."10

Plutonism, traditionally relegated to the realm of geology, which describes the formation of Earth’s rocks as part of a fiery, volcanic cycle, is resurrected by Lezama Lima to describe a "forma unitiva" ("unifying form), which is completely antithetical to the style proposed by the Council of Trent: "fuego originario que rompe los fragmentos y los unifica".11 This "originating fire" that destroys and unifies is indicative for Lezama Lima of the initial rupture and eventual "unification" of cultures brought on by the European colonization of the Americas.

While mestizaje has emerged as the "unifying" post-war cultural identity for many in Latin American and the Caribbean following an "ontological anguish before the need to solve their contradictions in a way that would validate their identity"12, the legacy of elite-sponsored miscegenation and vast, lingering racial discrepancies prompt a necessary reexamination of our perceptions of racial democracy in countries such as Brazil.

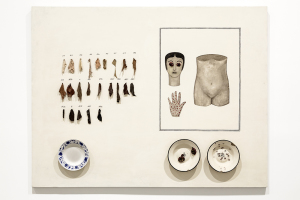

Adriana Varejão adeptly engages these complexities through several pieces in the show that borrow from the tradition of Iberian casta paintings—figurative representations of the hierarchical system of race classification used by Spanish and Portuguese colonizers according to various levels of racial intermixing. Ex-votos e peles (Votive Offering and Skins) (1993) once again employs the dismembered human figure, gouged eyes, and a taxonomic presentation of two dozen "skin" specimens, arranged by color.

In Testemunhas oculares X, Y, e Z (Eye Witnesses X, Y, and Z) (1997) Varejão presents a triptych of disfigured self-portraits in which her altered skin tone, features, and dress make her appear Chinese, Arabic, or of Brazilian indigenous origin. One eye from each figure has been removed, placed on a tray in front of the painting, and sliced open, revealing tiny photographs that depict cannibalistic rituals inside. "In recreating three marginalized racial types that comprise the Brazilian population, Varejão reclaims the bodies that were devalued in casta paintings and paints them in a style typically reserved for the aristocracy."13

With Tintas Polvo (Polvo Oil Colors) (2013) Varejão revisits racial classification by referencing the results of a 1976 census that gave Brazilians the chance to identify their own race by providing a unique write-in descriptor. One hundred and thirty-six distinct varieties of skin colors were submitted, ranging from "a light mix", and "not so white" to "coffee with milk" and "big black dude". Thirty-three of the most poetic were transformed by Varejão into flesh-toned oil paints called "Polvo" after the Portuguese word for octopus, whose ink contains melanin. These pigments were later used to create another self-portrait triptych called Polvo Portraits I (Seascape Series) (2014) in which Varejão has once again intervened, altering her complexion to "produce a variety of racial versions of a unique self."14

While conversations about these pieces will undoubtedly center on issues of cultural appropriation and Varejão’s position of privilege as a not-visibly-Afro-Brazilian woman, it is important for viewers to remain conscious of projecting a U.S-centric perspective of race onto topics emanating from Brazil. While the British, and later (United States of) Americans prefer(red) a segregationalist approach to white supremacy, the Iberians sought the long-view erasure or demonization of blackness through the process of miscegenation and the creation of a new "Brazilian" identity.

Hence, a large portion of the Brazilian population can claim some level of mixed-race identity, though the majority may not know any of those details, as intermixing could have occurred as early as five hundred years ago. This may explain Varejão’s outwardly nonchalant comment, again while in conversation with Stothart, in which she said that she was not interested in rummaging through her ancestral past to discover specific cultural ties, she was Brazilian… she could be anyone.

Of course, the freedom to choose how one identifies as well as how one is to be portrayed, is in itself an incredibly privileged position and something Varejão would do well to own up to more directly—along with the present reality that the creation of this supposedly universalizing Brazilian identity did not eradicate skin-based prejudice in the country, nor are its benefits felt equally across the social spectrum.

Up to this point, Varejão’s use of gore, the rendering of mutilated flesh, has been largely symbolic, flat and graphic, pointing to the disjunctures between European perceptions of the Americas and the reality of lived experiences in the midst of brutal colonial missions. Towards the middle of the exhibition, the curatorial layout begins once again to pick up on a formal style employed by Varejão in the first room of the show, the "tortured geography"15 of the Mapa de Lopo Homem II.

Folds 2 (2003) and Parede com incisões a la Fontana-horizontal (Wall with incisions á la Fontana-horizontal) (2009-11) are pieces which visually bridge Varejão’s early interest in the azulejo tiles of Brazil with her more recent investigations into the architectural aesthetics of saunas and bathhouses. Although the latter piece admits to the unarguable influence of mid 20th century Argentine artist Lucio Fontana, Varejão’s incorporation of the medium polyurethane and her elaboration of Fontana’s spatial/dimensional preoccupations puts her work in a wholly different category.

In the above-mentioned pieces, along with the breath-taking Azulejaria "de tapete" em carne viva (Carpet-Style Tilework in Live Flesh), 1999, Varejão’s vicious treatment of the mutable oil paint on her canvas does not simply yield the void between the artwork and the museum wall we know to be there behind it; her tearing of the painting’s flesh produces a series of visceral outgrowths of such dynamic carnal terror as to remind the viewer of Paul Thek’s more organic sculptures and David Cronenburg’s existential bio-nightmares. With the liberal application of that previously mentioned polymer and a grisly crimson/violet palette, the visible innards of Varejão’s disemboweled tile paintings somehow manage to fascinate and attract as much as they repel. The viewer becomes like that incredulous St. Thomas in Caravaggio’s Baroque masterpiece, finger primed, entering the body of Christ.

Surely their stark compositional simplicity will guarantee the success of these pieces amongst visitors to the exhibition, but their minimalism should not detract from the ultimate message of Varejão’s exciting and intuitive methodology: to belong to a culture is to participate in the constant (re)construction of its past, present, and future… lest others build that image for you.

"I discovered I would like to be eaten up by some Indians of the Amazonian Rainforest. Not as a self-sacrifice, consciously, at least, but as a demonstration of the ultimate architecture -- to inhabit, to dwell, physically as well as psychically, inside the human beings who would eventually eat me."

—Juan Downey

- Adriana Varejão Carpet-Style Tilework on Canvases (Azulejaria “de tapete” sobre telas), 1999 Oil on canvas 95 x 140 x 38 inches Private Collection, New York

- Adriana Varejão Eye Witnesses X, Y, and Z (Testemunhas oculares X, Y, e Z), 1997 Oil on canvas, porcelain, photography, silver, glass, and iron Three canvases, each 33 1/2 x 27 5/8 inches; installation78 3/4 x 98 1/2 inches overall Collection of Frances Reynolds

- Adriana Varejão The Guest (O Convidado), 2005 Oil on canvas 98 ½ x 153 ½ inches Collection of Jones Bergamin

- Adriana Varejão Virtual Environment II (Ambiente virtual II), 2001 Oil on canvas 55 1/8 x 63 inches Collection of The Olivier Berggruen Trust

- Adriana Varejão Polvo Portraits I (China Series), 2014 Oil on canvas Two canvases, each 20 1/2 inches (diameter) Five canvases, each 20 1/2 x 18 inches Private collection, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

- Adriana Varejão, installation view, ICA Boston Left: Proposal for a Catechesis—Plate (Proposta para uma catequese—Prato), 2014 Oil on fiberglass 59 (diameter) x 9 7/8 inches Private collection, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

- Adriana Varejão, installation view, ICA Boston

- Adriana Varejão Votive Offering and Skins (Ex-votos e peles), 1993 Oil on various materials 51 x 67 inches MJM Collection

[1] [Author’s Note] Above, all instances of "American" are to be read as encompassing "the Americas"—all of the lands from Canada to Argentina that were impacted by European colonization beginning in the late 15th century, unless otherwise noted.

[2] Ben A. Heller, Encyclopedia of Latin American and Caribbean Literature, 1900-2003

[3] José Lezama Lima, El reino de la imagen, this author’s translation

[4] Anna Stothart, exhibition wall text

[5] John T. Maddox, AfroReggae: Antropofagia, Sublimation, and Intimate Revolt in the Favela

[6] Oswald de Andrade, Manifesto Antropófago, translated by Leslie Bary: "In English in original. Tupi is the popular, generic name for the Native Americans of Brazil and also for their language".

[7] Tejido is a word employed often by José Lezama Lima when discussing historiography. Depending on its usage, tejido could signify "flesh" or the result of a "woven" fabric.

[8] Ed. and trans. J. Waterworth, The canons and decrees of the sacred and oecumenical Council of Trent.

[9] José Lezama Lima, La curiosidad barroca, this author’s translation

[10] Ibid

[11] Ibid

[12] Ed. Irlemar Chiampi, José Lezama Lima’s La expresión americana, 1957

[13] Institute of Contemporary Art, exhibition didactics

[14] Ibid

[15] Édouard Glissant, Riveted Blood