An important link here is the adoption and stewardship of Art Club 2000 by gallerist and curator Colin de Land. He ran the American Fine Arts gallery in downtown Manhattan from the late ’80s and during the period encapsulated in the exhibition. He was unique in his idiosyncratic, often anti-commercial behavior in the art world. While mounting significant one-person shows of artists such as Cady Noland and Jessica Diamond (both largely represented in the exhibition), he would simultaneously engage in counterintuitive behavior, at least for the art market, like showing up at an international art fair only to display the unpacked crates of his gallery’s artists. De Land, too, had a sense that the half-life of art world cool had long stopped registering heat. His sometimes desperate, yet always uncannily apt, attempts to shake things up often resembled a truant rearranging of deck chairs at a Hamptons soirée.

Actual death, not too surprisingly, is almost everywhere a subject in this show. 1993 may have been the height of the AIDS crisis. Work like Nan Goldin’s photos documenting the demi-monde and its physical demise in works like Gilles and Gotscha, Paris, 1992—93, and the installation of one of Felix Gonzales-Torres’ light bulb garland pieces remind one of how prevalent a subject the after-effects of the virus were at the time. Gonzales-Torres wound up succumbing to AIDS, and his later works poetically captured that world stripped to its bare meanings in abject circumstance. Frank Moore painted more direct and hallucinatory visions anticipating his own death from AIDS in 2002. Moore was also an example of how the disease often radicalized an artist and his work, to the extent that he helped found Visual AIDS, the artist’s arm of ACT-UP, and conflated his own diminishing life with ecological themes of the degraded landscape. In his disarmingly whimsical Birth of Venus (1993), Moore depicts a hermaphroditic mermaid in a suggestive pose, yet washed-up on a tide line polluted by medical waste. An image also included here from Andres Serrano’s morgue series (circa 1992), Rat Poison Suicide II, doesn’t directly deal with AIDS, but rather allegorizes one of the era’s pervasive subjects, mortality and its abject body of evidence.

Gabriel Orozco (b. 1962 Jalapa, Vera Cruz, Mexico)

Gabriel Orozco (b. 1962 Jalapa, Vera Cruz, Mexico)Isla en la Isla (Island within an Island), 1993

Silver dye bleach print

16 x 20 in (40.6 x 50.8 cm)

Courtesy the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery, New York

1993 was also the year of the controversial Whitney Biennial curated by Elizabeth Sussman with Lisa Phillips, John G. Hanhardt, and Thelma Golden. This was the one of the first large shows to attempt to frame artists incorporating social politics into the contemporary aesthetic dialogue. A critique one could address to NYC 1993: Experimental Jet Set, Trash and No Star is that it too closely resembles the Whitney show of that year. A large percentage of the same artists are represented in both shows. Works like Kiki Smith’s Virgin Mary and Pepón Osorio’s The Scene of the Crime (Whose Crime?) are representative of artists who were in both shows. Osorio’s installation seem almost lifted whole from that Biennial. The fact that many of the New Museum curators have had professional experience within the Whitney also might raise some issues of an institutional meta-narrative guiding the choices in the show. Writing about the 1993 Biennial in a contemporaneous New York Times review, Roberta Smith states, "In the end, this ambitious show illuminates the pitfalls of politically inclined art far more than its triumphs." In 2013, when socially engaged practice is part of a burgeoning growth area in academic curricula and curatorial studies, Smith’s statement might be taken as ether nostalgically naïve or cautionary. Perhaps with the distance of twenty years the curators of the New Museum show had hoped to reexamine the fomenting genesis of the current "social turn" in contemporary aesthetics.

There is much strong work in this show. Standouts include Jason Rhoades’ DIY tactics of strewn suburban detritus in Garage Renovation (New York), and Nari Ward’s Amazing Grace, which assembled over 300 discarded baby strollers in a boatlike array. Both of these artists’ installations work an abject aesthetic reminiscent of the Nouveau Réalisme and Arte Povera movements in France and Italy in the 1960s. The early ’90s in New York were a brief time of austerity that one can almost look back with fondness to, considering the scale of current economic challenges.

In 1993 it was still possible for artists to not be instantly aware of what each other was up to, even in New York City. Personal and visionary work had its own room, small as it was, in which to spend its creative adolescence. One of the most interesting questions arising from the slice of life/time that this exhibition provides is that life and times today, because of the technocratic "social," seem so compressed into static feedback loops that zombify our ability to claim a distinct cultural moment. The aforementioned institutionalization of political activism and dissent in art makes some of the funky, ground-up approaches to cultural intervention evident in the exhibition look antiquely radical. A certain nostalgia for random acts of transgression haunts NYC 1993: Experimental Jet Set, Trash and No Star, chiding impudently from a more fully fomented past.

- Courtesy New Museum, New York. Photo: Benoit Pailley

- Courtesy New Museum, New York. Photo: Benoit Pailley

- Nari Ward (b. 1963 St. Andrews, Jamaica) Amazing Grace, 1993 Approx. 300 baby strollers and fire hoses Dimensions variable Private collection Courtesy the artist and Lehmann Maupin Gallery, New York and Hong Kong

- Right: Paul McCarthy (b. 1945 Salt Lake City, UT) Cultural Gothic, 1992 Metal, motors, fiberglass, clothing, compressor, urethane rubber, and stuffed goat 96 x 96 x 96 in (241 x 235 x 235 cm) Rubell Family Collection, Miami Courtesy New Museum, New York. Photo: Benoit Pailley

- Felix Gonzalez-Torres (b. 1957 Guaimaro, Cuba—d. 1996 Miami, FL) Untitled (Couple), 1993 Light bulbs, porcelain light sockets, and extension cords (two parts) Dimensions variable Collection Mr. and Mrs. Jeffrey R. Winter Untitled, 1992—93 Billboard (two parts) Dimensions variable Collection Sammlung Hoffmann, Berlin Courtesy New Museum, New York. Photo: Benoit Pailley

- Gabriel Orozco (b. 1962 Jalapa, Vera Cruz, Mexico) Isla en la Isla (Island within an Island), 1993 Silver dye bleach print 16 x 20 in (40.6 x 50.8 cm) Courtesy the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery, New York

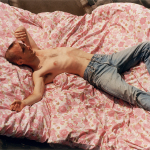

- Wolfgang Tillmans (b. 1968 Remscheid, Germany) Moby lying, 1993 Inkjet print 47 x 71 in (120 x 180 cm) Courtesy the artist and Andrea Rosen Gallery, New York

- Pepón Osorio (b. 1955 Santurce, Puerto Rico) The Scene of the Crime (Whose Crime?), 1993 Mixed mediums 112 x 244 5/8 x 146 ¾ in (284.5 x 621.3 x 372.7 cm) Permanent Collection, The Bronx Museum of the Arts, Purchased through funds from the H.W. Wilson Foundation and the National Endowment for the Arts, 1999.1.4 Film equipment courtesy BronxNet.Tv, Scribe Video Center, and Film and Media Arts at Temple University Courtesy New Museum, New York. Photo: Benoit Pailley

- Nan Goldin (b. 1953 Washington, D.C.) Gilles and Gotscho, Paris, 1992—93 Four Cibachrome prints 30 x 40 in (76 x 101.6 cm) each Courtesy the artist and Matthew Marks Gallery, New York/Los Angeles Courtesy New Museum, New York. Photo: Benoit Pailley