"Within and around a given work exists multiple forms of space, among them the area between the body and the work, its dimensional space as a container for materials and gesture (painted or otherwise), and its architectural—and contextual—support," writes co-curator Evan Garza in his comprehensive catalogue essay that deftly chronicles the evolution of painting as illusionary to painting as relational or sculptural. "Above all, the painting itself is insistent in its three-dimensional presence as a thing."

Conceptualized through Garza’s Not About Paint at Steven Zevitas Gallery in the Summer of 2011, in PAINT THINGS he and Deitsch have assembled works by eighteen contemporary artists who resist categorization through their works’ insisted presence through psychical and metaphorical strategies. PAINT THINGS commences with Jessica Stockholder’s Kissing the Wall series (early 1990s) and accentuates the unremitted dialogue between painting and space in contemporary art making. While not overtly political, the exhibition grapples with the evolved meaning of space and presence in light of the current sociopolitical climate. Bound to each other physically and philosophically, painting and space are never neutral, as Kate Gilmore’s Like This, Before (2013) and Wilson Harding Lawrence’s Sift (2010) and Grade (2012), all included in PAINT THINGS, attest. Though different in approach, aesthetic and theme, examining Gilmore and Lawrence’s works together allows for a multifaceted assessment of how materiality and methodology of traditional art making is engaged in order to explode the possibilities of process, gesture and monument.

Kate Gilmore, Like This, Before, 2013, video, wood, glass, paint, 6 x 18 x 8 feet (approximate), Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Clements Photography & Design, Boston.

Kate Gilmore, Like This, Before, 2013, video, wood, glass, paint, 6 x 18 x 8 feet (approximate), Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Clements Photography & Design, Boston.Gilmore’s Like This, Before is a large-scale "performance-based installation" in which white paint Abstract-Expressionistically cascades down one black, wooden roof-like structure, pooling in a bed of jutting, fragmented glass shards and dripping the onto the ground beneath. Ultimately this produces an object like a deconstructed Frank Stella black-and-white stripped painting (late 1950s).

To the left of where the structure is placed on the deCordova’s second-floor gallery is a video playing on a monitor. It shows Gilmore, dressed in black and white business clothes and heels, ascending the structure and pushing, one-by-one, glass vessels of white paint over its edge so that they sliding down and break, the paint swirling around the pieces of glass.

The Brooklyn-based Gilmore, who exhibited several older works in Absent/Present, a recently closed two-person show at Montserrat Gallery, was commissioned by Deitsch and Garza to create Like This, Before specifically for PAINT THINGS. She says that this work is much more of a "longer, slower piece" than her earlier works.

"It is more process—moving around the structure, setting things up in a very systematic way," explains Gilmore of the departure from works such as With Open Arms (2005). In Like This, Before the every-woman character that Gilmore plays is costumed in a humdrum, no-frills corporate uniform of dress suit and heels. This character is determined, but she’s more pragmatic and resolute than before in Gilmore’s earlier work.

"The early work was more full of angst and faster moving," says Gilmore. "I think as I get older, the pace is changing . . . this piece in particular is really dealing with the history of macho painting in a very obvious way, while work in the past always touches on this, but never directly addresses it."

Similarly, in both Sift and Grade, Lawrence, who has a studio in Pawtucket, obliquely engages with AbEx’s hyper-masculine legacy. In both, his primary material is the gallery wall itself, which he elegantly transforms from architectural structure into stoic, graceful picture plane. In Sift, the composition is created by striping away the wall’s surface so that its insides are exposed in tonal, textural cadence; in Grade, a sheath of wall is partially-slit and left to curve softly and rest its bottom edge on a white, wooden shelf, creating just a trace of shadow. With Sift, Lawrence references Mark Rothko in his gradated, modular tonal shifts and hewn texture, while with Grade he addresses the Zen of second-generation AbEx painters like John Cage. In both, he’s alluded to mid-century painting’s interest in opening up and exposing the inside—the essence—of a thing.

"Taking something that’s really in your head, that’s so abstract and being able to make it physically into space and being able to say, ‘that’s what I wanted to say,’ is such a nice feeling," emphasizes Lawrence.

All around the world, by the late 1940s, painters were approaching and entered the canvas as they never had before. "Just as the world had been fundamentally changed by the circumstances of the atomic age, so had the canvas," Garza writes, discussing the intervention of the three-dimensional into the two-dimensional picture plane. "The surface was now a spatial field that existed beyond compositionally implied dimension. The dimension could be real."

Both Gilmore and Lawrence probe the dimensionality of the painted surface in their works in their marriage of high and low art materials. In Like This, Before, Gilmore uses glass for the first time in her practice. "I wanted to work with a vessel that would reveal its color immediately and dramatically fall apart," she says. "I also wanted to use something relatively domestic to make something very "high artish."

That Gilmore’s character is dressed in the typical office work-wear of the American woman, ridiculous in its functional femininity, and matches the paint and support of the piece, further imbues Like This, Before with a sense of duality and reciprocity of high and low cultures. "I listen to the radio a lot when I am driving and pick up little phrases that stick in my head," says Gilmore about the piece’s title. "Often things that sound cheesy, but when put into a serious context could mean something else. Or, I think about cliches and how to make a cliche real." By highlighting the cliche of a female office worker hard at physical work in her videos, Gilmore critiques the oppressive power structures of corporate Middle-America via the language of sculpture and painting.

Similarly, through his use of everyday, cheap building materials, Lawrence elucidates the high craft of laborers and the harmonies of simple building construction. "Sheet rock is just crap," says Lawrence. "But once it becomes a museum wall, it becomes kind of precious."

Lawrence, who teaches at Eastern Connecticut State University, describes works like Sift and Grade as "wall drawings," as they blend painterly gesture with the rudiments of configured space. This body of work grew out of his 2010 thesis exhibition at Massachusetts College of Art and Design, wherein he was determined to purely use the space he was given, and simply sanded down a wall. Since graduating with his MFA, Lawrence has worked as a carpenter and wall preparator at the Guggenheim in New York. These jobs have helped him learn both the language of carpentry and the potentiality of spatial painting.

"The whole world communicates through written and verbal language—we learn how to verse our thoughts through this abstract thing," Lawrence says. "If you’re someone who finds it very difficult to communicate through that language, you have to find a different outlet. Especially when you want to talk about abstract things."

Difference is subtly championed in both Gilmore and Lawrence’s work. As Garza writes in his catalogue essay, the three-dimensional painting bred a spirit of protest and inclusion. "By letting in the world, through the inclusion of the artist’s body or simply the unorthodox use of the gallery wall, the artists featured in PAINT THINGS present us with a continuum from these historical precedents that demonstrates the power of artistic gesture to impact our view of the world, and vice versa," writes Dina Deitsch in the catalogue’s introduction.

Gilmore, who graduated from both Bates College and the School of Visual Arts, has long explored power structure and female agency in her work, probing struggle and historical precedents with equal force. "I’m a sucker for the against all odds genre," she says. Her work also concentrates in dismantling hierarchy. Interested in "defying what is expected of you and going beyond what one would assume," Gilmore grew up in Washington, D.C. She describes the capital city as one where "hierarchies are prevalent and obvious."

"I think growing up so close to this has to inform what you do," she says. "I am very aware of those who are the insiders and those who are kept out. I think my work tries to address and force a way in."

Lawrence emphasizes the "politeness" of visual art to shift peoples’ perceptions of space. By "being honest, and true to the materials," Wilson exposes a frank but poetic visual vocabulary that challenges our notions of space and spatial order. "Once you deal with three-dimensional space you’re opening up a whole other language," he says.

Lawrence gently exploits the expectations viewers bring to the gallery space in order to develop the possibilities of what we can see. He doesn’t deconstruct or de-contextualize through these wall drawings. He’s simply exposing what’s already there so we can see it for what it truly is.

"What I love about art, visual art in particular, is that it’s very polite, in a weird way," Lawrence explains. "Like an oil painting—all it is is color put together in space, and you go to it, and it has pictorial space or something in it, but it’s not saying or doing anything, your brain is doing everything. What I love about it is that visually, you do things at your own tempo, and it takes you somewhere."

A note of respectful remonstration, of optimistic protest, reverberates throughout PAINT THINGS. "The void isn’t what it used to be," wrote Christopher Knight in his L.A. Times review of Destroy the Picture: Painting the Void when it was on view at MOCA. And certainly this is true for the artists presented in PAINT THINGS—just as Occupy derived from the 1968 international student protests, artists like Gilmore and Lawrence have inherited the vocabulary of AbEx and the Situationists. But the idiom is entirely their own, and it’s one that’s encouraging rather than dispirited, hopeful instead of desperate. PAINT THINGS is rooted in the possibility of painting and what our relationship with it can be, and thus underscored is optimism and buoyancy as opposed to doubt and anxiety. Be it a "container" or a "void," in PAINT THINGS the painted space is an opportunity to expand the visual field.

- Wilson Lawrence, Sift, 2010, Museum wall, 52 x 24 x —½ inches Courtesy of the artist

- Kate Gilmore, Like This, Before, 2013, video, wood, glass, paint, 6 x 18 x 8 feet (approximate), Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Clements Photography & Design, Boston.

- Wilson Lawrence, Grade, 2012, museum wall and wood, 14 x 54 ¼ x 6 ½ inches. Courtesy of the artist.

- Claire Ashley, DOUBLE DISCO, Two performers, spray paint on PVC coated canvas tarpaulin, blower fans, and backpacks, 2012. Rehearsal still, Defibrillator Performance Space Chicago, IL Courtesy of the artist

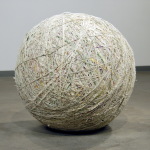

- Analia Saban, The Painting Ball (48 Abstract, 42 Landscapes, 23 Still Lives, 11 Portraits, 2 Religious, 1 Nude), oil, acrylic, watercolor on canvas, 2005. Image courtesy of Thomas Solomon Gallery, Los Angeles, CA. Photo: Joshua White.

- Jessica Stockholder, [JS 462]; framed oil painting from TJ Maxx, green plastic, brown plastic, bamboo bead mat, yarn, cloth, copper, plastic bits, thread, lexel caulk, oil and acrylic paint, hardware; 2008. Courtesy of Anne & Joel Ehrenkranz.

Based on an email interview with Kate Gilmore on February 21, 2013 and a studio visit with Wilson Harding Lawrence on February 23, 2013.