There’s no question that Bruce Davidson is a lion of twentieth century photography, and with good reason. His silver gelatin prints are atmospheric, transporting viewers to a rough and tumble 1960s Harlem neighborhood. Like the work of Lewis Hine, Walker Evans, and W. Eugene Smith, Davidson’s photographs are momentous time-capsules that seal a social reality so profoundly and poignantly that they are at once both humane works of art and the records on which social and political policy is written. Except that they’re not. Unlike the foregoing humanistic photographers, Davidson did not motivate the political will to effect real progressive change in inner city Harlem. And I wondered why.

As I walked through the East 100th Street exhibition on view now at the Museum of Fine Arts, I overheard a refreshingly straightforward question, which, I realize, should have been the one I posed instead: Why Harlem? It’s a simple question, but like so many seemingly simple questions, only raises more (and more complex ones at that). Indeed, why did Davidson choose what was, at the time, allegedly the most dangerous block in New York City? He had spent many years up to that point documenting the Civil Rights Movement; perhaps his deep concern for social justice motivated his interest in East 100th Street? Perhaps, as a documentarian, he understood the timeliness of such a project? But like any great photographer with a developed sensitivity for composition, Davidson knew where to stand to get his shot.

His work reminds me most of Robert Frank’s quintessential The Americans. Dark and underexposed, these are photographs that show us the painful lived realities of inequality. Like Frank, Davidson is an outsider. But he is eventually invited inside. Davidson, we learn, does not tell a sad story. It’s more complicated than that. Yes, we see poverty in his work, dilapidated apartments, junk heaps, cheap beer, juke boxes, and the iconography of religion and nationstate, American flags and portraits of JFK. But we also catch more than a glimpse of families, mothers with babies, children at play, and neighbors gathered around doorsteps, in short, of community. Of forty-three prints on view, seventeen of them (I counted) feature babies or children. Often an easy way to pull heartstrings, as classic as Madonna and child, it does not seem as if Davidson is interested in producing propaganda pieces with these portraits.

And this is perhaps why his work is not the impetus for policy. If we are to believe Davidson, it does not matter why or how he came to East 100th Street. But as a white photographer in a primarily African American and immigrant neighborhood, we would be remiss not to ask "Why Harlem?". His photographs are, in a way, voyeuristic. Davidson and much of his audience are voyeurs, looking at social landscapes they will never truly experience. But is Davidson’s work exploitative? Is it merely a window for middle-class museum-goers to look through and forget? I don’t believe so. Davidson’s work is, through it all, deeply humanizing. He did not have an agenda, or seek to mobilize political will, or photograph tropes, or produce propaganda. As an outsider, he is wrong to think it does not matter why he choose Harlem. It does. But I believe his choice was made in good faith. Looking at Davidson's photographs, I believe he came to Harlem to reveal a mostly disregarded community. And, in his way, I believe he became a part of it in the role of community photographer, in an historical moment already characterized by deep social and political change.

But you don’t have to take my word for it. The exhibition, originally on view at MoMA in 1970, can be seen in the Art of the Americas wing between now and September 8. In terms of skill alone, it far surpasses the huge marketing ploy of Mario Testino, which ran concurrently through February 3.

- Untitled, [Close Up of Boy and Girl with Faces Together], from East 100th Street series Bruce Davidson (American, born in 1933) 1967–68, printed 1969 Photograph, gelatin silver print *Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Museum purchase with funds donated by Haluk and Elisa Soykan and the Ernest Wadsworth Longfellow Fund *© Bruce Davidson/Magnum Photos *Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

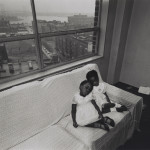

- Untitled, [Children on Couch with East 100th Street Out the Window], from East 100th Street series Bruce Davidson (American, born in 1933) 1967–68, printed 1969 Photograph, gelatin silver print *Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Museum purchase with funds donated by Haluk and Elisa Soykan and the Ernest Wadsworth Longfellow Fund *© Bruce Davidson/Magnum Photos *Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

- Untitled, [Couple on Rooftop], from East 100th Street series Bruce Davidson (American, born in 1933) 1967–68, printed 1969 Photograph, gelatin silver print *Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Museum purchase with funds donated by Haluk and Elisa Soykan and the Ernest Wadsworth Longfellow Fund *© Bruce Davidson/Magnum Photos *Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

- Bruce Davidson in the subway, New York City, USA. 1980 *© Bruce Davidson/Magnum Photos *Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

- Untitled, [Young Man Holding Baby in Luncheonette], from East 100th Street series Bruce Davidson (American, born in 1933) 1967–68, printed 1969 Photograph, gelatin silver print *Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Museum purchase with funds donated by Haluk and Elisa Soykan and the Ernest Wadsworth Longfellow Fund *© Bruce Davidson/Magnum Photos *Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Bruce Davidson: East 100th Street is on view at the Museum of Fine Arts until September 08, 2013.