Open Engagement is an annual conference on socially engaged art, focused this year on the topic of Place and Revolution. It was an incredibly dense three days of concurrent ninety-minute sessions, shorter fifteen-minute talks, opening and closing keynotes, and events throughout Pittsburgh featuring both conference-affiliated projects and ongoing work by local artists and community organizers.

A strength of OE is its inclusion of a wide breadth of what qualifies as socially engaged art, as participants gather for an opportunity to evaluate how a social practice can have an impact in the art world and as social change. Speakers—artists, curators, and other practitioners—presented on a range of work, from the expressly political applications of art in radical movements to aesthetically driven placemaking interventions. Aligned with the latter, the weekend featured Two Itinerant Quilters, in which Lenka Clayton and Joanna Wright cut diamond-shaped holes from attendees’ clothes and replaced them with new fabric, creating both a standard quilt made from volunteered materials and a walking-around-quilt of people with matching patches in their shirts. One of the weekend’s keynote speakers, Rick Lowe of Project Row Houses, described the qualities of such an artwork in an OE publication, expressing that a major purpose of socially engaged work is "to focus on the general mundane things of social life, social activities that we don’t have the capacity to take in any longer." The implication is that this process of focusing-in scales up, in the same way all civic engagement might improve when people are culturally connected to the place where they live.

In a rapid-fire conference, it is difficult to parse how a gesture like Two Itinerant Quilters stacks up against work being done by groups like the People’s Paper Co-op, an organization that generates artwork as an advocacy tool in their partnerships with formerly incarcerated Philadelphia residents and the nonprofit Philadelphia Lawyers for Social Equity (PLSE). One of the topics that came up over and over again at OE was the need for better metrics when measuring the success and impact of socially engaged art, to find some standard so that projects do not fall, sometimes unjustly, on a spectrum somewhere between bad artwork and bad community organizing.

Social practice can be a form of action research, either standing alone or in concert with the work of others. Producing socially engaged artwork, however, is not a substitute for being an actual member of a community or a movement, and the ability to author a project does not necessarily qualify an artist to take on a leadership role in an existing struggle. Part of the power of working as an artist is the freedom to move across professional disciplines, and many at OE talked about how they subvert their title or practice in order to work where they might not otherwise gain a foothold. It is a tactic that has served many, but outside of highly specialized labor, this fluidity of method is afforded to all—artists are just really good at accessing it. When it is treated as a rarefied skill, artists hoard the agency that belongs to everyone. When white artists drop in as privileged organizers in vulnerable communities of color, it replicates the dynamics of oppressive power structures that are already at play. Couple that with the number of artists who are working in an area temporarily as they earn a degree, and the result is a sustainability problem that mirrors current critiques of organizations like Teach for America. These are deep-seated challenges everywhere, and something for Boston artists to be aware of as MassArt’s moves through its strategic plan for academic years 2015—2020, which rolled out last fall and included the line item "Create a Social Practice MFA major by 2018."

Questions surrounding artists’ roles in communities of color came up over and over again at OE, though it was often a timid lament without answers. The Michelada Think Tank hosted both a mixer and a workshop and maintained a drop-in meeting space for practitioners of color and their allies, ensuring that these topics were at the forefront of the conference beyond individual sessions. Justseeds ran an exceptional conversation, one of the last of the weekend, where six of their thirty cooperative members were on-hand to discuss their working process. They offered carefully considered perspectives that can come from working through these kinds of issues in a partnership, and they were transparent about what it has taken to intentionally shift from a group of white male punk printmakers to a more diverse cooperative. Surprisingly, the weekend included very few opportunities to hear from rural or remote placemakers, and that narrowed field highlighted the problems of working in urban areas while disconnecting them from the challenges associated with making socially engaged artwork everywhere. OE will certainly be a place where new ethics for artists are vetted and codified, but for now it reflects a tight focus on a limited set of issues.

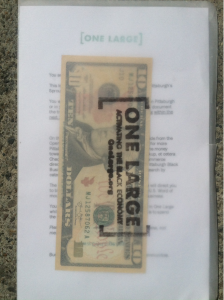

Pittsburgh was an outstanding site for a conference on place and revolution. There are long term projects throughout the city, ranging from the high profile Conflict Kitchen to Love Front Porch, artist Vanessa German’s community workspace that grew spontaneously when she opened up her personal practice to her neighbors in Homewood. Pittsburgh shares the same post-industrial blight, failed revitalization initiatives, even the barriers generated by physical geography with smaller Massachusetts cities like Worcester, but it benefits from being several hours from the next urban cultural center instead of one. It is more pressing that Pittsburgh transform into a thriving, liveable city, and so efforts on the ground level are both more urgent and more sustained. Organizations like the Sprout Fund have been at work for over a decade, offering financial support to all types of civic engagement projects, including the creation of artworks. For OE, the Sprout Fund supported One Large with a $1000 grant that Cindy Croot and Joy Katz split evenly among a hundred artists who pledged to spend the money at a black-owned business locally or at home. The project’s methods were an interesting response to the pressing questions asked at OE. By its nature, it asserted that participants can be trusted to be equal partners and carry out a project unsupervised by the creators. Though there is a documentation component, One Large highlights that the real work artists must do is as neighbors and citizens, interacting thoughtfully with their community as people in all fields must. With regard to the specific challenges faced by socially engaged practitioners, the answer is probably to keep talking. OE reconvenes next year in Oakland.