In the middle of the Pacific Ocean, past Hawaii but before Japan, is a collection of landmasses called the Marshall Islands. When the Europeans finally came calling in the early 16th century on their exploration ships there was trepidation, but having been settled by the natives since the second millennium BC, John Marshall discovered not only a deep understanding of the land but also the water. Traveling only by canoe, the Marshallese would use stick charts to map the 1,156 islands and islets surrounding them. Traditional stick charts not only mark the location of islands through placement of white shells, but they also note wave direction. This was done by lying in the bottom of the canoe and feeling the motion of boat in the water. Traditional stick charts of the Marshall Islands and their means of creation became the starting point for artist Michael Childress for a cerebral journey.

In this new body of work, Childress creates seven different charts for the intangible. He delves into the various spaces in his own mind to pull out visions connecting the left and right side of the brain. Upon first observation of the show, there is this temptation to have a knee jerk reaction and write the series off because seven canvases have zero visual connection, even to his starting point of stick charts. Seeing this, some might be inclined to shout, "Amateur!" and leave the gallery with their nose in the air. Perhaps it’s a reaction based on the decades of art world conditioning by critics that say we won’t accept bodies of work that don’t share some sense of visual commonality, making a show feel like riffs of the same melody and eventually we forget that each melody is initially made up of a series of notes. I sat on a table on the far end of the room, with the ability to view all seven canvases trying to collect my thoughts. I finally saw that these seven works represent a series of unrelated musical notes that don't really come together to make any unified sound, but somehow work better as unique visual mantras.

Childress arrived at University of Massachusetts in Amherst as an undeclared major with an interest in biology. Though it may seem like he took a left turn away from science and toward the fine arts building on campus, sometimes a curiosity to discover more about life and living organisms manifests in unexpected ways. Childress worked his way backwards through the university’s fine art program with a camera and a graphite pencil in hand, but after graduation he found himself sharing a studio space in Northampton with two oil painters. Soon he became mesmerized by color, an element that he definitely experiments with in this show. It is important to mention Childress’ interest in experimenting with other mediums because even though this is a painting show, it is more accurately described as a show that utilizes paint to work out the artist’s concept, rather than the work of a painter.

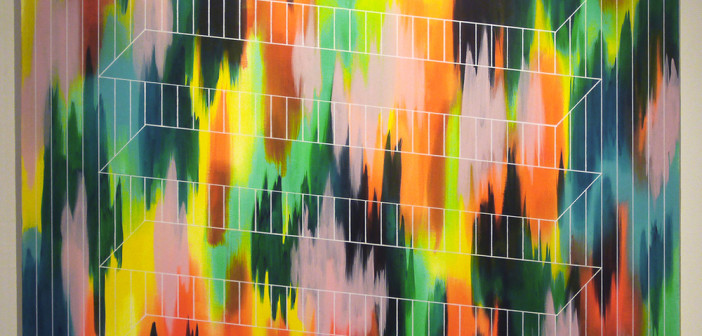

According to the exhibition statement, the seven canvases refer to different frames of reference on a seven-point compass, each attempt to represent movement through space. When the work was described, I expected interpretations of literal movement through literal space, like an updated contemporary version of the stick chart, but what this show truly navigates are the inner visions and movement of Childress’ own meditative mind. Though Currents and Peak of the Mystic Mountain are more representational images, the work is a combination of linear and non-linear work, challenging both sides of the brain. Childress used unrelated starting points in each work to keep from becoming disenchanted with his experiment and chose seven canvases rather than six or eight to move away from expected and previous use of symmetry. Though that explanation seems easy enough, seven is actually a very important number and ironically there are seven parts of the brain. Even if the show is not meant to express each part and still maintains Childress’ own vision, that tidbit adds a little something extra to concept and personal process of viewing and understanding the show.

Geometry is addressed in two of the works, one of which features glow in the dark paint; while others are seemed like mental tangents. Ultimately in a room where the work feels disjointed, Wax Tablet, the image chosen to represent the show, is arguably the strongest of the seven due to its minimalist raw quality and its ability to abstract a mental landscape. The work also bridges the gap between Childress’ main exhibition and his drawings shown in another area of the gallery.

Although drawings are not prominently featured in the gallery, they are additions to Yellow Peril’s flat files project. At first glance, the drawings seem chaotic, but Childress’ shows mastery of line, texture, and flow in each work. These are elements that also exist in the paintings, but looking at the drawings, there is a deeper understanding of a raw abstraction that morphs into something that appears almost representations of maps or landscapes. The drawings also feel less experimental than the paintings, like he’s pulled some of these field drawings directly from the intimacy of his sketchbook.

After grappling the layout of the main show for a while, the conclusion is that they don’t feel like a visual connected body of work because they aren’t and that was the artist’s choice. After all if the works felt the same, then they clearly wouldn’t represent seven different frames of reference. It’s a choice that some may disagree with or not understand, like myself initially, but I don’t think it shows a lack of thoughtfulness or talent, in fact it shows courage. Although, I won’t call Childress a masterful painter, he is part of a new wave of emerging artists who seek to try new things unapologetically in order to explore personal hypotheses, regardless of conditioned expectations. He might never be defined by just one medium, and that’s exciting. Childress’ reminds me that the less fearful you are to take chances and make mistakes, the greater the rewards will be in the long run.

- Michael Childress, Plane Ascension

- Michael Childress, Field Drawings Image courtesy of the artist

- Michael Childress, Field Drawings Image courtesy of the author

Navigation Paintings by Michael Childress is on view at

Yellow Peril Gallery in Providence, RI - Friday, 15 February though Sunday, 17 March 2013.