My first question is: Why Botero? How did this mild, sometimes trivial artist become the chronicler of darkness?

At age 73 Fernando Botero broke out of his benign reputation with a series of 100 works—50 paintings and as many works on paper—depicting prisoners being tortured at the Abu Ghraib prison camp in Iraq. In them we know the torturers, U.S. soldiers, by reputation—a boot or a stream of urine is all that’s shown. Their impersonality is significant, as it avoids the "rogue element" excuse offered by some authorities; they become anonymous and archetypal at once. The prisoners bend and twist their bodies, naked or near-naked, bruised and bound, in agonal contrapposto. The paintings are life-size, brightly colored, and difficult to look at. They are also the best work Botero has ever done. They were exhibited in Rome, Künzelsau, Athens, New York, Berkeley and Vigo, Spain1 and elsewhere. Much of the series was donated to the University of California, Berkeley Art Museum in 2009.

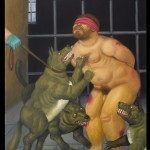

The Abu Ghraib series, painted by Botero over the space of a year or so, is akin to a close-up and claustrophobic Last Judgement or Dante’s Inferno, in a modern way; certainly some would see them as such: the sinful getting their just desserts from the righteous. I’ll let theologians parse that: the devils in hell as instruments of righteousness. The tortured are alone or in small groups, their figures a giant step beyond the plump blandness associated with Botero’s work. They have the massive, almost cumbersome musculature inspired by Michelangelo or the Caracci, steroidal and distorted to comic book proportions. It is as if a manuscript illuminator—I think of Jean Colombe, who completed the Très Riche Heures of Jean, Duke of Berry (c. 1412-1489, Musée Condé, Chantilly)—got a peek forward in time, saw Michelangelo’s work and tried to replicate it. For the first time in his career Botero gives muscles weight, but not the powerful weight of strength: the body becomes an additional restraint from which the tortured must try to escape.

Botero grew up in Medellin, Colombia, and has long balanced the pre-Colombian influences of his youth with a canny knowledge of art history. The surface simplicity of his work could easily consign him to irrelevance, a cousin to the naïfs, a modern version of the Douanier Rousseau. There is more than a hint of the darker side of Rousseau in the Abu Ghraib paintings; the dogs in A.G. 45 and 52 (2005), for example, would be right at home in the Douanier’s jungles. Both men share a similar eye for color, and both stand at a distance from realism.

Botero’s plump people normally have a lightness, as though they were inflated and might bob off the ground, their puffy feet unable to anchor them. The figures in a Pixar film have more weight! Botero’s interest in anatomy has always been expressive rather than scientific: the thumb of the tied hand in A.G. 67 is undersized; the legs of the man in A.G. 72 are unnaturally long in a way reminiscent of Mannerism. This clumsiness may actually add to the effect, drawing these scenes closer to some imperfect, eyewitness account than a picture-perfect scene would. Even more than Michelangelo, who is said to have painted as a sculptor, Botero’s Abu Ghraib figures seem carved, rigid in their solidity, looking back to even older artists. No, perhaps carved is not the right word, though there is an angular quality that suggests carving in wood; shaped might be better. Botero’s figures prior to this have been all roundness; in the Abu Ghraib paintings he discovers angles.

The Abu Ghraib torture cells are nondescript, unimportant. For years this same facility was Saddam Hussein’s, and he made as bad, if not worse, use of it. Who the hell cares about interior décor when people are suffering? I think of Francis Bacon, and the bland spaces he filled with his own deep unease. The Abu Ghraib works are about more than unease, but they are not paintings of war. War is the excuse used to justify these actions.

The best artworks about war take a broad vista, as in Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s Triumph of Death (1562, Museo del Prado, Madrid) or Picasso’s Guernica (1937, Centro de Arte Reina Sofia, Madrid). Even the Douanier Rousseau’s War (1894, Musée D’Orsay, Paris), though not based on a specific event, spreads out across the battlefield. The Abu Ghraib paintings are images better suited for the small screen—torture for the television and Internet ages. They do not rehash art-historical references, but very contemporary artworks, not quotations but modern recollections of the past. Thank goodness there’s no postmodern irony—the pollutant that ruins a lot of contemporary political art—here. The stylized anatomy, the non-descript "Arab" faces (not unlike Colombe’s generic people); could they belong to computer-animated characters out of a video game? Yes, except that then no one would care what happened to them. Therein lies one problem. Though not portraits, these are specific individuals being abused. The victims are still alive—most of them, anyway—and deserve some greater recognition, even differentiation such as comes in history or religious paintings.

Comparisons to Francesco de Goya abound: to his Disasters of War (1810s), and especially to The Third of May, 1808 (1814, Museo del Prado, Madrid). To that last, Goya gave faces to a generalized crowd; as with Botero, the soldiers are ciphers. Today, everyone is ready for their close-up, and can create and distribute it on their own, and have it used in evidence against them. Picasso and Rousseau were interested in the emotions of war, not the individuals caught in its path, and certainly not the perpetrators. War is general, blurred by speed and heightened emotion. Pain is specific and stops time. Botero’s uniform handling robs living victims of their voice, diminishes them to icons or simulacra; though not as removed as the soldiers, they are a giant step from being human beings. We know each other by our eyes, our voices, our expressions. We do not get to know the victims of Abu Ghraib, and it is clear Botero does not know them. I recall a line by C. S. Lewis: "How can the gods meet us face to face till we have faces?" (Till We Have Faces, 1956) No one today is as outraged by Goya’s Third of May as Goya was himself. (And Goya painted that scene six years after the events, at the request of the Spanish government. Who will commission the "official" Abu Ghraib artworks? It’s not too late.) No one is completely immune to it, either. There is no solace, historical or otherwise, in Abu Ghraib.

For all the art world’s fixation on video and "new media," more traditional forms—the photograph, the painting—still carry a powerful charge. Botero’s minor masterpieces outshine the competition. This has not been a great era for protest or agitprop art, despite some fine works in augmented reality and plentiful, perhaps too plentiful, subjects from which to draw. Where is the great work from the Occupy movement, the Arab Spring, or in opposition to the US government’s domestic surveillance programs? There are good works, but no classics, and dismaying silence from most important artists. The Picassos of today—God help us, Jeff Koons and Damien Hirst2—produce gilded fiddles for every burning Rome, "timeless" works in the sense that they are devoid of any connection to world events.

And consider Robert Rauchenberg’s suite of illustrations for Dante’s Inferno (1959-60). Rauschenberg had always deconstructed the original context of elements in his works (his term "combines" refers to the assemblage of disparate elements) that when he reversed himself he produced a completely unexpected result—and his finest series. What Botero did, like Picasso and Rauschenberg, is to break with his established style or subject matter and set a new precedent. Picasso and Rauschenberg continued to dabble occasionally in political art. Sadly, Botero has not carried this new direction forward; neither has it left any imprint on his subsequent works.

Critics sometimes compared the Abu Ghraib series with Guernica, which is misleading. Both share a righteous anger harnessed to the artist’s skill, but not much else. Guernica is Picasso’s greatest work, arguably the greatest artwork about the violence of war made in the twentieth-century. He united his graphic skills to his outrage in a single work and freed himself from being merely the gifted diarist of his life; a Casanova who could draw. Guernica has become the image that defines the bombing of the small Spanish town, a memory and a memorial. It has enhanced and replaced the truth. Rauschenberg’s Inferno illustrations recast mythology in modern terms. Abu Ghraib is documented in photos taken by the torturers themselves, and written reports and testimony. Botero has chosen to expand the visual narrative, illustrating scenes that did not end up as souvenir snaps, while bringing to modern horror echoes of history.

We can see, thanks to photographs by Dora Maar of Guernica as it was being painted, how Picasso reworked and refined it, changing his visual language to amplify its impact. Guernica is a novel in one image; the Abu Ghraib paintings are short stories—horrifying ones, but all on the same theme and in the same voice. I’m not blaming Botero for not being Picasso—museums are full of great artists who weren’t Picasso—but, despite the critic’s good intentions, the comparison over-reaches. Picasso showed us terror in motion; Botero, a grim and horrifying tableau vivant.

I should complete my earlier comparison. The three Limbourg brothers (Paul, Herman, and Johan) decorated The Très Riche Heures at the order of Jean, Duke of Berry beginning around 1412. Even unfinished, it was the Limbourg’s masterpiece, and a stunning work of the illuminator’s art. After an epidemic killed the Limbourgs and the Duke in 1415, the book passed from owner to owner until Charles, Duke of Savoy, commissioned Jean Colombe to finish it. Seventy years had passed—coincidentally, as many years as passed between Guernica and the Abu Ghraib series. Art had changed over the course of the fifteenth-century; the archaic landscapes of the Limbourgs gave way to Colombe’s deep, naturalistic vistas. Colombe, though a lesser artist than the Limbourgs, rode ahead on the advancing waves of art history. Botero looks backward, from this world of ours that has barely (has it yet?) outgrown Picasso. For a more contemporary comparison I might have choose Leon Golub, especially his Mercenaries and Interrogation series from the 1980’s.

The comparison with the Très Riches Heures is a bit unfair; comparisons in art history tend to be unfair. Around and between the Limbourgs and Colombe lies a great chunk of history, much of it still ringing familiar in our ears today: The Hundred Years War, the War of the Roses, Henry V, Jeanne d’Arc, Agincourt. The Limbourgs and Colombe worked to serve their masters; Botero works for his conscience and, by inference, ours. In our day of Operations rather than Wars, and the ingrained cynicism of the times, how can Botero hope to compete?

For all my faint damns, no other artist who has attempted to depict Abu Ghraib—Richard Serra and Gerald Laing being just two of the most notable—has had as big an impact. Serra’s Stop Bush print, based on one of the notorious Abu Ghraib photos, was a quiet highlight of the 2006 Whitney Biennial. Laing produced a series of terrible Pop Art paintings, after having abandoned painting for thirty years. They are arty in-jokes—offensive, but in the wrong way—small where his anger hoped to make them large, filled with the antiwar rhetoric of an older generation that now rings artificial in our ears.

The change of century seemed to have wrought change in Botero, as though some form of millennialism darkened his outlook. In the mid-1990s he began painting scenes from the drug war in his native Medellin, including the killing of drug lord Pablo Escobar in 1993. Violence seemed anomalous to his well-fed, self-satisfied people, and translated onto canvas with negligible success. Elmer Fudd shooting Daffy Duck packs a more visceral punch. Not until then was Botero been able to step outside his tropes and capture pain and humiliation. Age lent a deeper focus to his anger; the Abu Ghraib series is more intense than anything he has done before or since. Botero became the unlikeliest of doomsayers, his work a belated and welcome flowering in the ashes of a sad world.

Is there a museum in the world so resistant to today’s militant conservativism that could devote its (limited) storage and exhibition space to this series? Years have gone by but the Iraq war is no less controversial; the indefinite, legally questionable detention of people at Guantanamo Bay is an open sore. Is Botero’s reputation great enough, and are these works great enough, to justify occupying the space the Abu Ghraib series requires? Perhaps Botero produced too many paintings. He risks inuring his audience by repetition. They are best seen in person, though walking through the entire series can be a grueling and numbing experience. He should break up the series; spread the word from museum to museum. Seeing one at a time does not dull their cumulative impact, but may even augment the experience. In one place, they are easily avoided; spread out across the country, they are a constant reminder, a prickling of the conscience. Whatever he does, they should not lie in storage somewhere, to be forgotten when they are still relevant. The clock is ticking; Botero has returned to his insubstantial works of inflatable people. New scandals have replaced the old, without any being resolved.

Pain and misery are cousins to much of the best art, and war, as Klaus Honnef put it, is "The Father of all Photographs" echoing Saddam’s famous "Mother of all Battles" quote.3 Botero looks without flinching at the price we pay from our humanity. But disasters and death have become raw material for the media; how many times have the Abu Ghraib photos been shown? How many times a day? Giving a damn should not be a choice, but it is. These Judgements are not final, to our joy and dismay. Because the clock has not stopped we live the repercussions of the times, sometimes helplessly. As W. H. Auden put it, "Those to whom evil is done / Do evil in return."4

It does not matter if you believe that the events at Abu Ghraib were the work of a few rogue soldiers or whether you believe there was complicity higher up. The message of the Abu Ghraib series is the same. Guernica is only marginally about Spain and the Nazis; it is about suffering in war throughout the ages. The Abu Ghraib paintings are about the terrible things human beings do to one another, regardless of country, politics, and in the face of centuries of hard lessons—that is what these two extraordinary artworks share. Their message, to quote Auden again: "We must love one another or die."5

- Fernando Botero Colombian, b. 1932 Abu Ghraib #45, 2005 Oil on canvas University of California, Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive Gift of the Artist, 2009.12.25 Photographed for the UC Berkeley Art Museum by Benjamin Blackwell

- Fernando Botero Colombian, b. 1932 Abu Ghraib #52, 2005 Oil on canvas University of California, Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive Gift of the Artist, 2009.12.29 Photographed for the UC Berkeley Art Museum by Benjamin Blackwell

- Fernando Botero Colombian, b. 1932 Abu Ghraib #67, 2005 Oil on canvas University of California, Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive Gift of the Artist, 2009.12.42 Photographed for the UC Berkeley Art Museum by Benjamin Blackwell

[1] Abu Ghraib-El Circo, at the Casa das Artes de Vigo

[2] Feel free to provide better nominees. Please.

[3] Ingo F. Walther, ed., Art of the 20th Century, Taschen, 2005.

[4] W. H. Auden, "September 1, 1939"

[5] ibid.