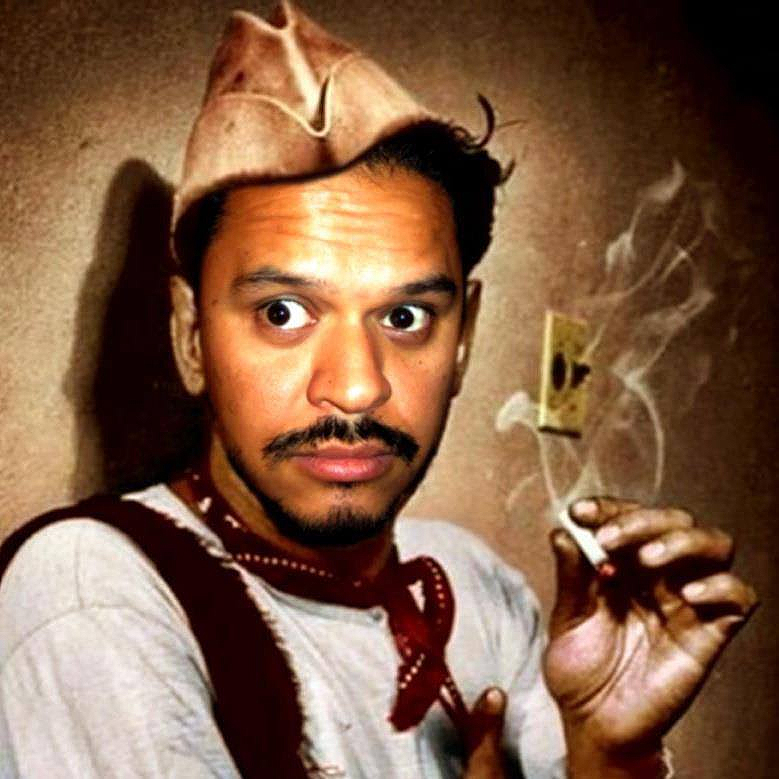

Raúl Gonzalez has caught fire. Now 37 years old and a practicing artist since he was a teenager, over the past few years he has become visible to an increasing number of people through a series of ambitious, well-received exhibitions in and around Boston. Raúl lives north of the city with Elaine Bay, an accomplished artist he met while growing up in El Paso, Texas, and their son Raulito. On October 25, he and Elaine will be the featured artists in an exhibition titled Wake Up Call at the University of New Hampshire Museum of Art. In large part, the show will be an extension of the world Raúl depicted in Los Nuevos Guerreros (The New Warriors) last summer at Carroll and Sons, but with additional characters and a significant three-dimensional environment created by Elaine.

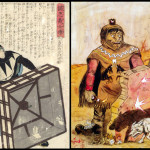

UNH curator Kristina Durocher perceives Wake Up Call as an important meditation on repression and survival among people living in violent regions of Mexico. And, as Raúl might add, among people everywhere. The characters he will present are inspired, in part, by the actions and psychology of characters found in the book 101 Great Samurai Prints featuring the work of by nineteenth-century print master Utagawa Kuniyoshi. But Raúl has made the images his own by re-rendering them with references to cartooning, politics, contemporary life and the shared American-Mexican desert.

I sat with Raúl over beer to discuss his career, the upcoming show and his history as an illustrator, cartoonist and painter. Open and eloquent, he wove through the conversation his perspectives on everything from politics, to being Mexican American, to the need to inspire people to be who they are. The final topic he’s addressing with writer Cathy Camper in a book series titled Lowriders in Space, which they are designing for all children but also, as Raúl put it, as a love letter to Latino kids.

Jim Kiely You’ve been a busy man. You’ll be one of two people in Wake Up Call this October at the University of New Hampshire Museum of Art. Could we start by talking about that show?

Raúl Gonzalez The exhibition is a culmination of three years of work that have been in exhibitions since 2011, beginning with Close Distance at the Mills Gallery, followed by Calendar’s Tales at 808 Gallery and ending with Los Nuevos Guerreros at Carroll and Sons. I meant each show to be a different chapter in a storyline, or as a different point of view in the world I call Tranquilandia. At UNH there are more chapters in the work, an expedition through denser land.

JK What’s the storyline?

RG It’s one that finds people thrust into a situation filled with violence, loss, insignificance and just the struggle to survive in such a place. Los Nuevos Guerreros was created as a way to cast a land with people in diverse situations and who are affected by them in different ways.

Amor no Muere, mixed media on paper, from the seriesLos Nuevos Guerreros (image courtesy of Carroll and Sons Art Gallery)

Amor no Muere, mixed media on paper, from the seriesLos Nuevos Guerreros (image courtesy of Carroll and Sons Art Gallery)JK In that work, what’s happening to the people, the warriors, is clear, but they themselves could be either living or barely living or even dead—that’s unclear. Will any of them be part of the exhibition at UNH?

RG Yes. There will be 101 guerreros going to UNH but not all of them are the ones that were shown at Carroll and Sons.

JK What is the intention of bringing together your work with the work of Elaine Bay for the UNH show?

RG She and I—we've been together and we've known each other for many decades now. I met Elaine when I was 16 years old, around the time that I was finding a place where I could fit in. That place happened to be the journalism room of Coronado High School in El Paso, Texas. A teacher, Peggy Ligner saw that I could draw so she would just keep throwing assignments at me and I’d produce illustrations for the school paper, the poetry mag, and the school yearbooks. Lo and behold, one day this cute girl named Elaine Bay picked up my sketchbook and she liked it. I saw that she liked it. The rest is history, as they say.

As for why we were thrown together for the UNH show, it’s simply because Elaine is an important part of the world that was created for the exhibition, which is called Wake Up Call. Elaine's work is important in that she adds female perspectives to a lot of the issues that take place in Tranquilandia. In large part, the issues she deals with are the disappearance of women from the desert town of Juarez, Mexico, the low wages they're paid in maquiladoras [Free Trade Zone factories] and the disrespect they are shown from some of the male figures in that world. Where my work is two dimensional drawings and paintings, Elaine brings in sound. She brings in video. She brings in sculptural elements that very much become a piece of that world. Her work lines up perfectly with mine and makes it more powerful.

JK One thing I’ve noticed about your warriors is that, despite the hardship and brutality they endure, there is no sadness. Other emotions, but not sadness. Based on what you just said, it seems Elaine's work might draw some of that out of them.

Ayudanos! (detail), installation of found objects, wood, paint, photographs, audio and video components; installation to be included in Wake Up Call, Elaine Bay (image courtesy of Elaine Bay and Raúl Gonzalez)

Ayudanos! (detail), installation of found objects, wood, paint, photographs, audio and video components; installation to be included in Wake Up Call, Elaine Bay (image courtesy of Elaine Bay and Raúl Gonzalez)RG It absolutely does. It brings a lot out of my work. One of the great things about what we do together (and this comes from being in a relationship for so long) is borrow from each other. I borrow imagery from her; she borrows imagery from me. We've grown up together over the past decade so we don't really even have to have a conversation about what we're doing. We pretty much know what the goal is. Missing from my work was a female perspective, which is such an important part of the story. Because Elaine is from the same border town, she understands the setting. And also, since she worked as an assistant to a documentary filmmaker when she was in college, she understands the people and the victims and can explore it all through her own practice.

JK I know the curator of Wake Up Call, Kristina Durocher, is excited even though the show hasn’t been assembled yet.

RG Yeah. [laughs]I'm wondering how that's going to work. There are about 135 different works of art going up there. They're not all things that can be framed and hung on a wall. There's a sculptural piece that Elaine has, which resembles a fountain in the middle of a Mexican courtyard but made up of different television sets and makeshift crosses. There's a totem of television sets with images of weeping women. There are decapitated heads that rotate over the floor. These decapitated heads are masked with disco ball tiles. There are sheets, narco banners and all sorts of stuff that's pretty complicated to install.

JK Could I ask you about your own style? You frequently refer to yourself as having started off as a cartoonist. What do you see as the difference between cartooning and what you're doing now?

RG That's a great question, because I've known what I’ve wanted to become since I was a young boy. Starting at 15 years old, I would take the Rapidos Turismos bus from El Paso to the San Diego comic book convention with my comic book pages to show editors and other comic book artists, hoping that they’d hire me and I could just drop out of school and leave everything behind. It never happened. [laughs]They were always really kind to me, but would send me on my way with a bunch of criticism. I was always saddened by it, but I would go back home and start on a brand-new series of drawings for the following year.

JK Taking their advice to heart?

RG Taking their advice to heart. And things got better every year . . . The big difference between what I was doing then and what I'm doing now is in the type of conversation I’m having and who I’m having it with. When I was working on becoming a cartoonist, I was doing it to make books in a certain genre and for a comic book reader base. Today I’m conversing with dead artists and moments in history, and I’ve received much wisdom from them upon viewing their works and reading people’s stories. It all helps me better understand the present and to reflect it in my work. For instance, with the guerreros I pull from a lot of different wells; from the Japanese prints I based them on, to Mexican murals, to early-American folk art, historical events and whatever the hell else. I like to fill gaps in these different moments with my work.

JK Is another difference that, as a cartoonist, you're illustrating a series of concepts to get a storyline across, but in your studio work you have to get the story across in one frame?

RG I guess I'm a storyteller when I'm a cartoonist and I'm a storyteller when I'm working toward an exhibition. With my exhibition work, the story's much more open ended: it doesn't have to be a clear beginning, middle or end so it’s up to the viewer to construct a storyline. I really love that about this type of art, and I also like that it's mysterious to me as I'm creating it.

JK It seems that you've worked out your own iconography of cactus, snakes, sombreros, skeletons and little death masks.

RG I'm not sure if it's my own iconography, but it is iconography that I feel very comfortable using and that I feel makes the points I want to make in any given piece. The cacti really help create the setting of the work: you know that you're not up in the Northeast when you look at the work. Because of the cacti, you feel like you're in the desert. The colors themselves are very sun bleached, as if the paper has been left outside for too long. That comes from just growing up in the hot, hot sun, where even advertisements on the back of buses are completely drained of color. I try to include all of these types of feelings in my work. I want people to walk away almost remembering the smell of a certain piece, even though it didn't smell like anything.

JK Other imagery. You have a series of characters that have single horns in the middle of their foreheads. One of the characters from your show at Carroll and Sons that sticks with me is a woman consoling a fallen warrior who has . . .

RG A chichón. Basically a bump that sprouts from your head after you bumped it.

JK Like Elmer Fudd?

RG [Laughs] Yeah, exactly. And that's exactly what she's trying to do. She's a mother figure, a wife figure, someone who just cares for that fallen person. What is that gland in your brain that makes you aware of things?

JK The pineal gland?

RG Yes, it's an overly developed pineal gland. The people in my work, they're aware. They're completely aware of the situation. A lot of times, people say that, well, awareness allows us to avoid things or to solve problems, and I feel that my characters are perfectly aware of what's happening around them. But either which way, [laughs]they can’t do anything about it! They’re stuck where they are. That's something that people go through daily. They’re stuck in situations and aware of what's happening. They might want to change it, but that's just like, a cruel joke in a way.

JK You also depict a lot of children in your work.

RG Yes, and there's a certain thing I've been doing with children. I think about how violence changes who they are from one second to the next. In my work you see children with heads like yours and mine, except younger . . . [laughs]with fewer lines on them! Next to them is the self that they’ve shed. You see that their heads have split away. To me, this shows that they are no longer the people they were. You might not be able to see this in them physically, but inside they are no longer the people you knew just five seconds before. It's because of what they've seen, what they've witnessed, what they've experienced. That's a symbol that I use repeatedly in my work now. I guess the first time I did that was with a work called Born Again.

JK First time I saw Born Again, I wondered whether it depicted a cruel joke of reincarnation, where people come back as themselves.

RG Would that be so cruel, though?

JK Rather than as an eagle or a blazing star, to come back as yourself?

RG No, the boy in that work is no longer who he was but he’s still here. It’s something that happened to me, a personal thing that I won't discuss. One second you could be an innocent, then suddenly something happens and you can just forget about all of that previous stuff. You've become someone completely different. The way you perceive the world from that point on is completely different. It could be either a positive change or a negative change. It could be a combination of both.

In Born Again, I used a lot of Christian iconography. The boy looks like he has wings, but they’re actually two dead roosters hanging over his shoulders. Born-again people who are saved by the Lord Jesus Christ or whatever . . . they feel like they’ve become someone new. I went to a Christian school when I was a young boy, a born again Christian school, and I always found that line baffling.

JK Which line is that?

RG To be born again. To be born again through the blood of Jesus Christ. I always found that baffling. I never accepted Him into my heart—fortunately—so I was always wondering what people meant. It was like: "What happened? You're not in diapers. You're not new. What does this mean?" I understood it as a young boy, what it meant, but it was never for me a religious thing. It wasn't because I was saved or anything like that. It was because the experiences changed who I was as I travelled through life.

JK You're constantly shedding skin.

RG Constantly shedding skin, yeah.

JK As we sit.

RG As we sit, exactly. You never know. This conversation might change who we are! [laughter]

JK Why did you say fortunately when you said you didn't accept Jesus into your heart?

RG I think it's too simple, too simple to accept the Lord Jesus Christ into your heart, because you immediately ignore everything else about the world with all its questions and all its mysteries. You feel like you have the one answer, and I don't think that there is just one answer. I think it's okay for an adult to be that way. If that's how you want to live your life, that's perfectly fine. But I feel that when you try to impose that on a youth, especially youth who have so much to learn and so much to give, that you are unjustly taking away their curiosity and also what they might accomplish on this planet during the short life we all live. I feel very fortunate that I've always had a rebellious streak in me, because if I hadn't, everything that I've done to this point in my life I never would have attempted. I would have been, I guess, happy to go to listen to Charles Niemann every Wednesday and Sunday, give him ten percent of my measly wage and . . .

JK Do the things you're supposed to do and pretend it's your destiny?

RG Exactly. I don't think that should be the life of a youngster. You can have that in old age. [laughs]

JK Getting back to your painting Born Again, for a second; I believe it’s from a series you made about a time in Baja. Is that right?

RG No, no. Something that I try very hard to do in my work—and one of the reasons it's accessible to so many people all over—is not to give specific cities or places. Because the people that are going through what they're going through in my work, these are people that exist all over the planet. Baja, Juarez . . . you could switch locations to any place where there’s poverty and suffering, and you'd find people in the same predicaments.

JK Right. I think that tends to be lost in this country when people talk about what’s happening in Mexico; the disappearances and poverty, the violence. We isolate all of it as though it were unattached to anything going on around ourselves. You know, specifics might belong to a particular area, but what’s happening is what humans universally do to each other.

RG Yeah, that's really true.

JK Your warriors are trying to hold themselves together physically, certainly, since sometimes their guts are spilling out . . .

RG [Laughs]

JK . . . but mentally and emotionally too.

RG Yeah, absolutely.

JK You have an aesthetic, a way of attracting people’s eyes to your work and then delivering an unattractive message. We had a back-and-forth about this on Facebook about the painting of a border crossing guard . . .

El Migra Contra Tecate, mixed media on wood panel (collection of Tim Donovan, image courtesy of Raúl Gonzalez)

El Migra Contra Tecate, mixed media on wood panel (collection of Tim Donovan, image courtesy of Raúl Gonzalez)RG Oh, that’s called El Migra Contra Tecate. Yeah.

JK What’s happening is that an immigration cop is pinning down somebody who has come over the border illegally. But the painting does two things. First, at least for me, it presents an image that’s homoerotic to the point of being, if not physically arousing, then mentally arousing.

RG It’s completely homoerotic. [Laughs]

JK Very appealing! Then when I really look at it, I notice that you’ve painted a little sweat mark on the mask of the character being pinned down. Literally and figuratively, I realize, this guy's about to be raped. It's not just this one man, of course, it's a whole group of people who are simply trying to go someplace to get a better life. You got me. You reeled me in then gave me something that's absolutely the opposite of the original impression. In this case, one was very attractive and the other repulsive.

You’ve made other paintings that pair beauty with treachery and hope with pessimism; first, though, you engage the viewer to look closely. One of the paintings is a mural of a little boy riding a wave across a Japanese woodblock type of sea. The beauty of it was the hook in this case, and then I saw eagerness . . . but then a barrier fence standing between him and the shore.

RG That one's called Nowhere to Go But Everywhere.

JK In another work, El Rio, a girl is crossing similar waters, scared but determined to get to her destination. The expression on the kid's face is: I can get through this! Then you look and see a death mask floating beside her and realize, well, maybe not.

RG Maybe not. That body of work is maybe 30 or 40 paintings. The title itself, Nowhere to Go But Everywhere, is a sentence fragment from On the Road by Jack Kerouac. I've always loved this theme in American literature, of travelling and, you know, trying to better yourself by exploring life in the world. I explored it through this series of paintings and drawings, mainly to show that it's our human nature to be nomadic and to search for the meaning of our own identities.

That's one of the things that have bugged me so much about not just border issues, but about our American life in general. It seems that the ways of exploring ourselves through travel have been crushed. With young kids they’re immediately told to go directly into school. There are walls being built. I think that's such a terrible thing to impose on humanity, the inability to find yourself through experience, to decide who you want to be. I think that's really what I was trying to get across with that series of drawings. The walls are financial and physical, and sometimes they are very much self imposed, like we tell ourselves there's only one way of accomplishing something. There's only one way that I could become an artist: I go to art school to get my masters. To me, that's a very dangerous solution. If it's the only one, it's not a good one. There should be multiple ways to live and dream and do what you want to do.

JK You're a dad. Has your way of thinking changed since you've become one?

RG I don't pay attention to whether my thinking has changed. There have been changes since my son was born, yes, but I don't know if I approach my art-making any differently than I did in the past. Well, that's not absolutely true [laughs]because since my son was born, or a month before he was born, my art started being recognized in many different capacities. I won awards and suddenly I was being asked to be in exhibitions, which had never happened before in my life.

JK After what, twenty some years?

RG Yeah, since I was 16. I'm 37 now. It was only four years ago that I began being asked to participate in all these exhibitions. That allowed me to really grow as an artist, to suddenly be asked to fill spaces with my ideas. I've been, I think, in 30 exhibitions in three years. All of this has happened as Raulito's been alive. He has become a large part of my art practice. I don't hide anything from him, and his hand is in a lot of what I produce. You can see marks that he makes on the paper itself. From little scribbles and marks to spills of Kool . . . well, he doesn't drink Kool Aid, but you know what I mean.

So, it's not that my thinking has changed; it’s that I've had commitments that I've been creating work for. I don't credit my ideas to specific people I've worked with, but if Liz [curator Liz Munsell]hadn't asked me to be in her show at the Mills, I probably wouldn't have created any of that work, which was large and I don't usually work large. And if Lynne Cooney hadn't asked me just four months later to fill up an entire space at the 808 Gallery (which I collaborated on with Elaine), I probably wouldn't have made that work. Things have changed a lot in the four years that Raulito's been on the planet with us! Now I always . . . I do look at him and I . . . it's just great to have this little kid around who's so alive and so innocent and so interested in the world.

[long pause]JK There’s seamlessness to what you do. In a single work you can pull together samurais and Mickey Mouse and geopolitics and economics.

RG Right. One thing I don’t do is define myself as any kind of artist, as a painter or cartoonist or somebody who draws. All of the above is what I'd say. It's about being present and digesting as much information as I can. I've always wanted to just make artwork about the types of people I know and love. When I moved here to Boston, I felt something was suddenly missing from my life: humble, hard working, brown skinned people.

I remember early on I would walk with Elaine through the MFA and love the work but feel there was something missing from it, you know? There were stories not being told. And I thought that the reason they weren’t being told was that some people are simply too busy to tell them. What I saw were stories about people who had already reached a godlike level. This really did change my focus. Before it I was interested in comic books and telling stories through the comic book format. Then I thought, what if I could tell stories in a museum setting about the people that I love and grew up with, whose stories are just as heroic or even more heroic than what I'm seeing here at the museum? That set my path for the next . . . I don't know how many years. I've been here 12 years now. I really credit that collection with having changed my direction as an artist and wanting to tell stories not being told in art history.

JK That's what you said at the beginning of this interview. You said your work fills gaps.

Illustration from the book Lowriders in Space (Book 1), written by Cathy Camper and illustrated by Raúl Gonzalez (Chronicle Books, Fall 2014) Image courtesy of Raúl Gonzalez and Chronicle Books

Illustration from the book Lowriders in Space (Book 1), written by Cathy Camper and illustrated by Raúl Gonzalez (Chronicle Books, Fall 2014) Image courtesy of Raúl Gonzalez and Chronicle BooksRG Yes, gaps. There are big gaps. I think: "What if a slave had had a paintbrush? What if a child working in a factory had had a paintbrush? What kind of stories would be next to these portraits of tycoons?" Yeah, and that's the type of museum I want to see.

Another thing that changed my thinking about introducing myself, my experiences, and who I am was teaching cartooning to underprivileged kids; to Latino kids in the Boston area, black kids in the Boston area. I would ask them to create comic book characters. They would immediately start grabbing the blue pencils, the yellow pencils, the peach pencils. These black kids and these brown kids, would start drawing people with blue eyes, white skin and blond hair, time and again. I would always tell them, "Think about your parents or think about the people who raise you. Think about the stories of your grandparents or of your ancestors. I want to see stories about the people you love, who surround you."

I realize it's important for me and for artists who are like me, or like others, to introduce ourselves to these kids so that the next time around, they're picking up brown pencils and black pencils to create characters that reflect who they are and who they love.

JK Was their reluctance that they didn’t see their own tribes as being superhero material?

RG Exactly! That bugged me. It’s one of the reasons I'm so very happy and fortunate to be working on a series of books called Lowriders in Space.

JK Let's talk about it. What’s the series about?

RG There are two books in the works so far. They’re being created by myself and my friend Cathy Camper; the originator. She was a librarian and noticed the same thing that I noticed: these books aren't out there, the ones showing American life through the lives of people who live here, in this vast country of ours. And so she said, I want to create a book called Lowriders in Space because there are Latino kids who love their cars, who love their lowriders. And I said, I'm the person who has to draw this book! [laughter]I know who these characters are. I know the people. I know all the in jokes. I know everything about it.

We immediately joined forces. Our editor Genny Seo, her mission statement is exactly that: to make books for the youth who live in this country. She wants to make books for Korean Americans, for Chinese Americans, for young African Americans, young Latinos, gay youth . . . but the books aren’t out there for them. That really makes a person feel like they don't belong, when they don't see themselves represented. Simply, what we're doing, we're not setting out to make a book that hits you over the head with Mexican-ness, or any of that stuff. The characters just happen to be named Lupe Impala, Elirio Malaria and El Chavo Flapjack. Those just happen to be their names, but when kids living in El Paso, or in LA, or up here in East Boston see them, they'll know that it's a love letter to them. It's also very universal, right? What kid doesn't love a car that blasts off into space? Come on! [laughs]

JK It sounds like the genre is buddy travel.

RG There are three buddies and the car, which is very much a character, yeah. The story is about the three friends who are artists and who come together to create something beautiful. That beautiful thing happens to be the lowrider. How they accomplish this is through hard work, teamwork and their passions. Then there's also that fantastical element of adventure, in that the car blasts off into space and actually gets detailed by the voyage through the Milky Way.

It has been very fulfilling for me to have this project become a reality. Being a comic book artist was the only thing I had dreamed about from when I was 13 on. Putting everything that I love about drawing into this book has been so rewarding. But I haven't forgotten, either, the type of boy that I was when I was that age. This was a boy who had absolutely no idea how artwork was made. I'm a self taught artist. I decided to skip schooling altogether. I remember that it was only my passion that fueled my desire to become that artist. I didn't know what tools to use, what type of paper to use, any of that. For this book, I decided to approach the drawings with the same kind of . . . what’s that word, naiveté?

JK Naiveté.

RG The same kind of naiveté that I had back then. I'm using the same tools that I used when I was 13, 14, 15 years old—the tools that I had lying around my house at that time. They were BIC pens, just cheap fountain pens, and newsprint paper. I'm not trying to draw anything technically accurate. If one tire looks like it's misplaced, that's perfectly okay. The book is just filled with the same type of energy and detail that I would include in my drawings when I was a kid.

JK A few years back you illustrated Philosophical Tales, an irreverent overview of the history of Western philosophy written by Martin Cohen, who was then the editor for the American Philosophical Society. The illustrations are the opposite of what you just said described. They’re exacting, and full of low- and tipped-angle perspectives that Orson Welles would have loved.

RG Yeah. [Laughs] There comes a time in your life when you try to be someone you're not. There's always that point. I feel that that book was me trying to be the illustrator that I thought I should be. It was one of the most difficult projects I’ve ever attempted. I feel the drawings aren't as accomplished as they would have been if I had been more confident of my abilities, or of my inabilities, which are just as important as anything else.

JK That's true of a lot of artists who look at their work in retrospect. There’s an early period where they're doing things that they think they should, then a period where they're doing things they wish they could and then, at some point, they hit a time where they're doing the things they actually can do.

RG Exactly. But I l still love that project, because I was 26, 27 years old and always willing to try anything. Jeff Dean, the editor, was such a great man. There have always been people in my life who have believed in me, and have made it nice to do things they’ve asked me to do.

JK That's beautiful.

RG Yeah, it's nice.

JK [looking at recorder]We’re getting near the end. Is there anything else I should be asking you?

RG No. I think we've touched all the topics. Kind of seemed like a stream of consciousness. I love what I do, and I also love sharing what I do. What’s so important with making artwork is sharing it with people. I love seeing what other people do in the community. It's nice to know that there are other people like you on this planet. It gives you the confidence to continue to create and to follow your zany ideas. [Laughs]

JK Is it important that you know people understand your work?

RG I don't necessarily worry about whether people get my work, whether they're offended by it, or whether it makes them laugh or makes them sad. I think those are all things that just are going to happen with any given work. That doesn't really matter to me at all. I know there are people it does move and touch. That, to me, is very important. I love the fact that I get emails from people from all over who really love a certain drawing, even enough to get it tattooed on their backs. But even if somebody completely hates it, that's okay too. That doesn't really bother me either. I have really thick skin.

JK Thank you, brother.

- Left: Okashima Yasoemon Tsunetatsu, Utagawa Kuniyoshi, from 101 Great‐Samurai Prints, edited by John Grafton (Dover Publications, 2008) Right: El Fragmento, mixed media on paper, from the series Los Nuevos Guerreros, Raúl Gonzalez (image courtesy of Carroll and Sons Art Gallery)

- Left: Yata Goroemon Suketake, Utagawa Kuniyoshi, from 101 Great‐Samurai Prints Right: La Quijada, mixed media on paper, from the series Los Nuevos Guerreros, Raúl Gonzalez (image courtesy of Carroll and Sons Art Gallery)

- Ayudanos! (detail), installation of found objects, wood, paint, photographs, audio and video components; installation to be included in Wake Up Call, Elaine Bay (image courtesy of Elaine Bay and Raúl Gonzalez)

- Amor no Muere, mixed media on paper, from the series Los Nuevos Guerreros (image courtesy of Carroll and Sons Art Gallery)

- Born Again, mixed media on paper (image courtesy of Raúl Gonzalez)

- El Migra Contra Tecate, mixed media on wood panel (collection of Tim Donovan, image courtesy of Raúl Gonzalez)

- El Rio, mixed media on paper (image courtesy of Raúl Gonzalez)

- Illustration from the book Lowriders in Space (Book 1), written by Cathy Camper and illustrated by Raúl Gonzalez (Chronicle Books, Fall 2014) Image courtesy of Raúl Gonzalez and Chronicle Books

- Illustration from the book Philosophical Tales, written by Martin Cohen and illustrated by Raúl Gonzalez (John Wiley and Sons, 2008)