I had only seen Wendy Richmond’s work once when I called her one morning in the spring of 2012. I knew of her work shown a few years ago at Carroll and Sons, and I was intrigued by her use of an accessible technology—a cell phone—to create simple, yet powerful, documentations of 21st century life. Thus I found myself that May writing a preview of her show, Navigating the Personal Bubble, slated to open at the RISD Museum in about a month. Wendy, along with the Museum, sent me images of the works included in the exhibition, and these images of large, straightforward projections of faces felt both usual and unfamiliar. By the time I was dialing Wendy’s number, I thought I knew, more or less, what I’d write about. A few minutes into our conversation, however, the core of my article had completely changed.

Richmond’s practice includes teaching, writing and image-making, and focuses on issues surrounding surveillance culture, the relationships between antiquated and cutting-edge technologies as well as creativity in 21st century. No stranger to Boston, Richmond co-founded the Design Lab at WGBH after first experimenting with new and old media at MIT’s Visible Language Workshop. Richmond has taught at MIT, International Center of Photography, Rhode Island School of Design, and Harvard University Graduate School of Education. Last winter she received a MacDowell Colony Fellowship, and she’s also received a National Endowment for the Arts grant, a LEF Foundation grant, the Hatch Award for Creative Excellence, a Rockefeller Foundation Bellagio Center residency and an American Academy in Rome Visiting Artist residency. Equally impressive is Richmond’s writing: she’s been a columnist for Communication Arts since 1984, and has published three books, Design & Technology: Erasing the Boundaries, Overneath and Art Without Compromise*.

I’m happy to say that my first conversation with Wendy developed into a collaborative dialogue of sorts. Last spring and summer, we semi-regularly corresponded via email, discussing everything from Wayne Thiebaud to Whitey Bulger as we honed in on the crux of her art making. These discussions, or "ping-pongs," as we initially called them, helped me sharpen my understanding of visual culture in the information age, as well as embolden my interest in my own creative practice. What follows is an exchange based on this correspondence.

— Leah Triplett

Leah Triplett I want to start off talking about your background. Will you discuss how you moved (no pun intended) from dance to visual art making? How are the two practices related? And how do patterns of movement, or choreography, influence your practice as a whole?

Wendy Richmond My background: I majored in art and design (and was involved in dance) in college; very soon afterwards, I began mixing traditional media with new technology at MIT, collaborating with programmers and other artists and designers. That framed the basis of my work: erasing boundaries between disciplines. (And is the subtitle of my first book: Design and Technology: Erasing the Boundaries.)

It was not dance, per se, that influenced my work, but physicality.

Here’s how:

1) Physical body

After working intensely with technology at MIT and several start-ups and also co-founding the Design Lab at WGBH, I had a sort of allergic reaction: I felt that computers were diminishing our physicality. (At the time we didn't have laptops or smartphones, and we were really chained to these grey "boxes".) That led to my taking a sabbatical to dance, in order to regain my body’s connection with the physical world. I added more writing and teaching and art-making, where I could delve into wide-ranging questions: what is technology giving and what is it taking away? So at that time, dance, for me, was all about revisiting physicality, and the desire to bring it back into design and art.

Wendy Richmond, Overneath cover. 2002-2003.

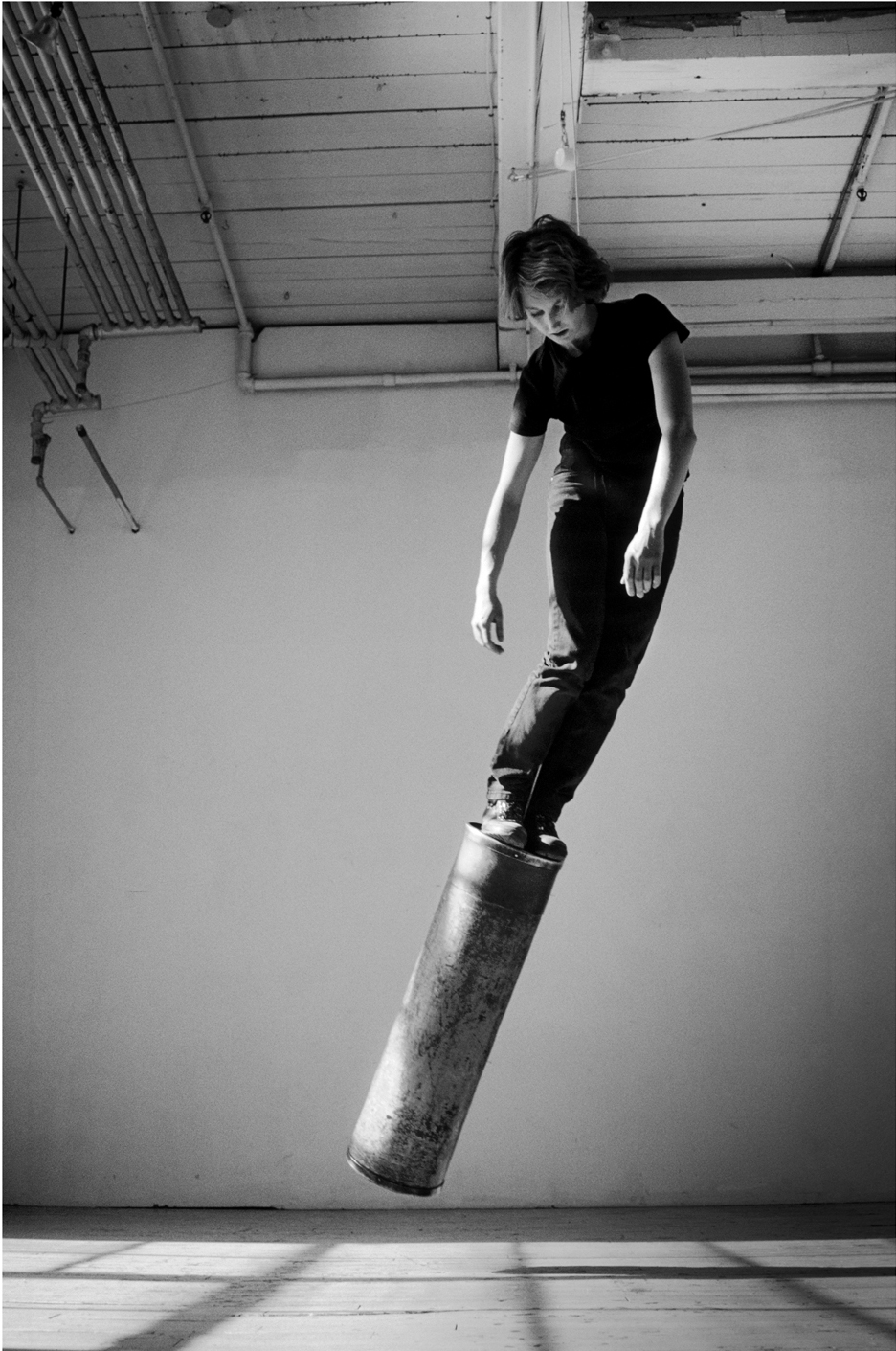

Wendy Richmond, Overneath cover. 2002-2003.2) Physical space

Space is a huge factor in my thinking about my art practice. The space that I work in tends to determine and govern what I make. Each working space I have had—whether it is a 1,000-square foot loft or a tiny cell phone screen—has completely affected the work. When I had a huge studio, I collaborated with a dance company in my studio ("overneath"). When I was traveling a lot, I started making work on my cell phone—in airports and on trains and city streets (Seen and Public Privacy). When I moved to NYC I did not have a studio, and I spent a lot of time in cafes. This led to overheard cell phone conversations, which I translated into an installation (Overheard).

3) Observing the mundane

Observation is a big part of my work—mostly of people in crowded urban environments. I am not interested so much in the people themselves, or their personal stories, as I am in their habits and their patterns of movement, and how these interact with the space and architecture of the city. This is about observing a city’s choreography through the rhythm of its dwellers.

LT Can you talk about how choreography is a communication? In other words, how does the viewer understand your work through choreography? I’m thinking specifically about the participants’ eye movement in Navigating the Personal Bubble (2012).

WR I always work in sequences. All of my work is a collection of short, related pieces. When I made the series Seen (cell phone etchings) I was arranging a series of single frames from short cell phone videos. After that, I started to use the video as the final product, and even then, the work was a series of videos.

So, in a way, my "choreography" is like Muybridge’s work: capturing movement in order to observe it more closely.

I don’t think of the eye movement in Navigating the Personal Bubble as choreography. Instead, it’s the gestures—the small, similar gestures that the participants share. That’s why I did that fourth wall of listed gestures at the RISD Museum. It was based at first on Richard Serra’s list of verbs (Verb List Compilation: Actions to Relate to Oneself). The participants in Navigating the Personal Bubble, while deep into their work, were also was engaged, unconsciously, in a series of shared verbs: e.g., frown, grin, raise eyebrows, roll shoulder, sniffle, etc.)

In terms of communication, I think viewers (audience) unconsciously engage in these same movements when they work on computers. People have told me that after seeing the installation, they became aware of their own immersion and unconscious gestures.

In other words, after people see these works (Overheard, Public Privacy, Navigating the Personal Bubble), what they do or see becomes consciously familiar. They are more aware of the environment they are living in.

Wendy Richmond, Overheard. 2008 - 2010.

Wendy Richmond, Overheard. 2008 - 2010.LT We’ve talked about the element of humor or absurdity in your recent work. How do you use humor?

WR I am finding that there is more humor in my work lately, especially in the videos and wall-writing/drawing I did at the MacDowell Colony. Humor is a vehicle to articulate an idea. What idea is that? Basically, the joy of discovery—discovery that happens by observing the mundane things around us, and allowing time/permission to play. My Studio Wall.

I started using humor by mistake. I knocked down rocks (Rock Work) and was surprised that people laughed when they watched my videos. The laughter came at the moment of surprise: a surprise of scale, sound, or the way the character knocked down the rocks. So I started thinking about humor, how it works, and why I use video. In video, there is the element of time, which you can use to reveal a surprise.

Wendy Richmond, Wendy Richmond Rocks TVs. 2013.

Wendy Richmond, Wendy Richmond Rocks TVs. 2013.In terms of absurdity, I had not really been that conscious of it, until MacDowell. And there, the absurdity came from feeling so free and open and permitting myself to play. This leads directly to the Theibaud quote, and your question:

LT I constantly return to this Wayne Thiebaud quote that you shared with me several months ago: "When an artist or viewer feels involved in a work, they relate to that work as a living thing, with a sense of exhilaration and freshness of spirit. . . . In contrast, finishing off demands is an intellectual process, a neat tying together of things in a way we ‘think’ is correct." You seem to be preoccupied with the space between the work as a "living thing" and the work as a document.

WR I have to add back the last line I wrote about Thiebaud:

"Thiebaud strives to forestall the ‘absolute resolution’ of a work, which can be ‘dangerously close to the art of taxidermy.’" (Taxidermy is just such a great image, and really makes the point of taking a work so far that it is just dead.)

LT I am glad you added that last line back in!

WR To me, this is about being OK with ambiguity, being OK with not delivering a very specific message.

In my book Art Without Compromise* and my Communication Arts column, I am very focused on my audience: my readers. I want to make sure that they get a very clear message from each column. I work really hard to make a single point, and take out anything extraneous. I know they will bring their own filters, their own stories, but still I am specific with my message.

With my artwork it is really different. I’m comfortable with ambiguity. I don’t want to deliver a message. I am happier to keep it open.

The best response for me is when someone has seen my work, and then weeks or months later, they say: "I saw something today that made me think of your work." Which really means, "I saw something today and I thought more about it because of you." Which in turn means, "I thought a little bit more today than I normally would have."

LT You’ve said that your work revolves around the pattern of choosing a setting with your camera and record, thus recording action within the frame. Can you explain how this pattern relates to the Thiebaud quote?

WR In this case, the quote refers to my desire to put more emphasis on observing and documenting, and less on directing. I set up my camera to frame a potential sequence. Yes, I direct the context and the visual framing, but then I hope that something good will pass by. And so I start it, but I do not direct an "absolute resolution."

Here is how I described it in my interview with Joseph Carroll: 1) I set up the camera carefully; 2) I press record; and 3) I let the action play out. My "presence" and "absence" is really similar. In Public Privacy, I see a scene that has potential in terms of visual beauty and interesting action. I hold the cell phone as still as possible, and shoot, without moving, for 15 seconds. In Navigating the Personal Bubble, I have given precise instructions to carefully chosen participants: go to a café or library, turn on Photo Booth in video mode, and record yourself working on your laptop for three minutes. So even though I’m not literally there, I have consciously framed the scene, then let the surprises happen. Similarly, in Wendy Richmond Rocks TVs, I come upon a scene with good potential and I set up the camera on a tripod; I’m very conscious of what I’m framing. Then I press record. The "character" (me) enters the scene and, in some random way, destroys the rock sculptures. I have no idea how she will knock them down.

LT I’m thinking about you starting something in your studio by sharpening a pencil with an old-fashioned sharpener, and letting the shaving trail off into space. It’s absurd, and the action incorporates the obsolete technology of a hand-turned pencil sharper. Throughout your career, you’ve used new technologies to make art, but you also use new technologies to revisit older ones (so to speak). Can you talk about the relationship between obsolete and cutting-edge technologies in your work? Is there a dichotomy between them? Or are they negotiating and complimenting each other?

WR First, I need to be more accurate about that pencil sharpener at MacDowell. That was the beginning of my allowing myself to do absurd actions. I came to the studio with nothing but a camera and tripod. I started to use the studio itself (its vast walls, heating system, changing sunlight, ladder, the snow outside . . . ) Again, the space determined my work. There was an old rotary pencil sharpener on the wall; I went to the dollar store and bought a bunch of pencils. One after another, the sharpener chewed up the pencils, leaving them to look like the snout of a furry dog or a splintered tree branch. (More absurdities inside the studio included testing gravity, making targets and throwing snowballs, shoveling snow, etc.). I was comparing new and old technologies by simply using what I had and what I discovered in the studio.

A friend at MacDowell compared this work in my studio with Bruce Nauman’s Mapping the Studio (Fat Chance John Cage). I found that a helpful comparison. Again, the space is a very important factor in my work.

In terms of cutting edge vs. old technologies, the cutting edge technologies that I use are consumer level, i.e., mundane, everyday, non-precious. In Seen, I consciously used etching and cell phone video as a way of investigating the differences between old and new. For example, the amount of time it takes to shoot a video (15 seconds) vs. the time it takes to create and print an etching (days). In my recent research, writing, teaching, and art, I am immersed in the current consumer (i.e. mundane) technology of smartphones.

Wendy Richmond, Seen. (2005-2006).

LT Can you talk about your recent ICP course, "Fifteen Second Videos on your Cell Phone" What surprised you about the course?

WR The social media aspect of the class was crucial. We all shot videos using Vine and Instagram, and posted them. In this way, we were always seeing each other’s work. Sharing peeks into one another’s real-time place and process engendered a sense of closeness and collaboration.

An example: After I saw a post by one of my students, I "liked" it and commented on it with a suggestion about lighting. A few minutes later, I saw her new post: a short clip using shadows. Another student recorded his own surroundings, playing off the shapes in the previous student’s video, and that got a visual repartee going. It felt like a cross between a classroom critique and a social media exquisite corpse. When the class ended we immediately started meeting for "reunions". We still follow each other’s posts. It became a physical/digital community.

So, although this class started as a way to create compelling short cell phone videos, it also became a class about understanding short video in the context of twenty-first century communities.

LT How does teaching courses like this one, and writing, affect your practice?

WR My writing, teaching, and art making are completely intertwined. Each one helps me to understand the other.

LT What’s the line between surveillance and observation in these works? I’m also thinking of Public Privacy (2009).

WR I’ll describe the difference between surveillance and observation with some thoughts about community:

I’ve been spending some time at BRIC, a center for community arts and media in Brooklyn. (BRIC’s new building houses 2 theaters, classrooms, a public access TV center, and a 3,000-square foot gallery, which also acts as a performance venue. All of its spaces are wired, with the intention of broadcasting events to Brooklyn households and beyond.)

There is a sign near the entrance informing people that they "voluntarily agree to allow (their) photograph and likeness to be used in any media." To me, the sign is a metaphor. It tells me that I am part of a community that wants to be celebrated and announced. Many activities go on here and we want to tell the world about it without worrying about who owns what, or copyrights, etc. It also means that I can take pictures and send them out into the world (which I do). In other words, it is the opposite of what we normally see: discreet/elevated surveillance cameras.

Wendy Richmond, Public Privacy. 2005-2007.

LT I love this comment. Surveillance is almost always discussed in a negative light, but in this context, when it’s agreed upon, it’s empowering.

WR One last thought:

When I am in the middle of a project, I have a sort of mantra: "What question is this column asking?" "What question is this artwork asking?" "What question is this class asking?" In other words, finding the question is the most important step in finding any answer.

Here’s an example from my Sept/Oct 2013 Communication Arts column "The Long Reach of the Very Short Video."

The question that this column is asking is: "Why is the short video important?"

As artists and designers, if we want to be innovative, or even relevant, we cannot ignore the framework that our work lives in. If we’re creating video work, we need to consider all of its contemporary contexts, from tools to audiences to digital and virtual venues. Remember Marshall McLuhan’s famous line "The medium is the message"? Today, the medium of video is most active in the realm of social media and smartphones. The short video’s potential for innovation and uniqueness lies in its mobility, brevity, easy-to- use tools, virality and the size and breadth of its audience. Together, this produces a frenzy of participation, a desire to follow and be followed. It’s the combination of all these characteristics that forms the new context.

So, the intersection of my writing and teaching and art practice is basically this question:

What is an artist in the twenty-first century?

Wendy Richmond, Overheard. 2008-2010.

- Wendy Richmond, Overneath cover. 2002-2003.

- Wendy Richmond, Public Privacy. 2005-2007.

- Wendy Richmond, Wendy Richmond Rocks TVs. 2013.

- Wendy Richmond, Seen. (2005-2006).

- Wendy Richmond, Navigating the Personal Bubble. 2012.

- Wendy Richmond, Overheard. 2008 – 2010.