What does it mean to sell something that does not have a definitive form?

In my exploration of this question, I will focus on the generation that has led to many misconceptions about the commodity status of art: the Conceptualists from the 1960s and 1970s. For the next several Marketwatch columns, I will look at an artist from this generation and pair him/her with a contemporary who might share similar sensibilities.

Many early critics, such as Lucy Lippard, tended to exaggerate illusions about the "dematerialization of the art object" and the artist's ability to subvert its commodity status. Artists like Carl Andre and Robert Irwin sold many works comprised of common and industrial materials, and as their fame rose so did the complications involving the treatment of their "common" steel plates and florescent lights. This generation of artists have changed how art is collected in many ways, but I am most interested in the artists who managed to create a following of collectors, and yet, as their careers progressed sold them increasingly fewer materials.

In Lawrence Weiner's career, one can follow a gradual reduction of form, from painting to ephemeral text displays, that is unrivaled in the history of niche market formation. The works that Weiner began during the early 1960s called the Propeller paintings appropriated the motif of the TV test pattern. At the time compared to Jasper John's Flag paintings as well as Lichtenstein's cartoon works, reviews commonly said Weiner was more interested in the "idea" of a painting, as opposed to an actual painting. However, viewing some of Weiner's installation shots from his 1964 exhibition at Seth Siegelaub Fine Arts Gallery, decisions were made about the scale of the propeller in relation to the canvas size, how large the outlines around the propeller in each work related to the frame, not to mention his distinct color palette. In other words, Weiner was making painting decisions, not simply proposing ideas about paintings.

A body of work followed in which "painting" decisions were further limited. In each Removal painting, a small rectangular notch was removed from the bottom frame of the canvas. These, unlike the Propeller paintings, were not hand painted, but made with a spray gun and compressor, further removing the hand of the artist. In addition, Weiner gave instruction to anyone receiving the work: "The person who is receiving the painting would say what size they wanted, what color they wanted, how big a removal they wanted." [See Alexander Alberro's "Conceptual Art and the Politics of Publicity]. Weiner was including his patrons, the market he inhabited, in the evolution and creation of his work.

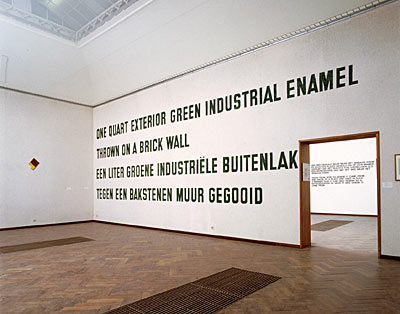

If Weiner could take out a corner of a painting, how would he devise the removal of a painting from itself? This delicate procedure can be found in works like One Quart Exterior Green Industrial Enamel Thrown on a Brick Wall and Two Minutes of Spray Paint Directly upon the Floor from a Standard Aerosol Can. The linguistic utterance becomes as important as the act itself. These works preceded his infamous "Statement of Intent" that guided the structure of his subsequent work:

1. The artist may construct the piece

2. The piece may be fabricated

3. The piece need not be built

Each being equal and consistent with the intent of the artist the decision as to condition rests with the receiver upon the condition of receivership.

Weiner's "Statement of Intent" carved himself a very niche market, presumably, the precise one he wanted to occupy. Over the course of almost a decade, Weiner managed to lead a handful of collectors and patrons to buy and sell immaterial works of arts. Alberro states that Weiner, along with Joseph Kosuth, Carl Andre and Dan Flavin presented "one of the most radical critiques of the commodity status of art in the twentieth century." While I tend to agree, it is important to note that none of these artists wished, or even thought possible to abolish art's commodity status. Weiner was trying to occupy a different market than had previously existed. His increasingly spare and non-existent materials were not an abolishment of the art object, but an expansion of what could be bought and sold. Joe Scanlon suggested he "expanded the value system of art" by ultimately minimizing capitalization, production and exposure.

Many artists have since produced textual and "de-materialized" work, but none quite as rigorous as Tino Sehgal, who has found a seemingly inconceivable niche by "producing something and nothing at the same time." Sehgal, born 1976 and now based in Berlin, has gained notoriety in recent years for his choreographed "situations" in which paid participants act out instructions. In This Is New, an attendant quotes to a museumgoer a headline from that day's papers: only the visitor's response can trigger an interaction that concludes with the work's title being spoken. Other works include "This is So Contemporary," in which uniformed museum guards dance around the room singing, "This is so contemporary, contemporary, contemporary," that was shown as part of the Venice Biennial in the German pavilion in 2005.

Unlike many performance artists from the past few decades that have built lucrative careers off the slick documentation of their performances, Sehgal limits how his work is bought and sold in very disciplined ways. No material transformation can accompany any of his works: no photographs, videos, catalogs, written contracts or bill of sales. Purchasing is conducted orally, in the presence of a notary. His work operates within the "normal" conventions of commerce, yet he has drained any material from that convention.

Both Weiner and Sehgal occupy what could be a very advantageous position. Many museums have committed money and resources to housing the likes of Richard Serra, Jeff Koons, and other artists that demand extensive overhead costs to maintain. These costs cannot survive exponentially; which makes the likes of Tino Sehgal and Lawrence Weiner very effective in adapting with these works. Curator Yasmil Raymond described an encounter in which she did not know a Sehgal was on display: “He had a Dan Flavin, a Larry Bell and a Dan Graham in the corner," she explained to the New York Times. She continued: "The minute I entered the space, the guard came in and started stripping. I slowly crawled behind the Dan Graham. I was so embarrassed I didn’t know what to do with myself. I wanted to know the title of the piece, and I had to wait. At the end, when he takes off all this clothing, he says the title and then puts his clothes back on. It was called ‘Selling Out.’” In an economy that is only beginning to recover, the way Sehgal "sells out" never felt so necessary and liberating.

- Installation view of Lawrence Weiner’s One Quart Exterior Green Industrial Enamel Thrown on a Brick Wall.

- Image of Two Minutes of Spray Paint Directly upon the Floor from a Standard Aerosol Can.

- image of Tino Sehgal NOT performing one of his pieces’s with children.

All images are courtesy of the artist's and Google image search.