It was a tripartite collaboration that happened only once: in 1979 choreographer Lucinda Childs, composer Philip Glass, and artist Sol LeWitt came together to create the signature performance work of the minimal period, DANCE. Of course, with hundreds of steps, thousands of feet of 35 mm black-and-white film, and millions of notes, "minimalism" is a persistent but hardly apt label. Glass has preferred to describe the music from this early period as "working with repetitive structures." Childs' dance at the time was largely non-narrative and plainly dressed, and LeWitt's drawings and paintings often restricted to series of lines drawn with or without a ruler. But when people (most often critics) use the term "minimalism,' they usually mean work that is not florid. This does not mean, however, emotion-less. Emotion and expressivity are most evident then they are contained within and supported by a form, and thus DANCE is a deeply emotional work.

Recent various funding efforts have permitted Childs to digitally restore the late LeWitt's films and revive the piece for a modest tour of the U.S. and France. As I write, she is in Gainesville preparing her company for performances at The University of Florida. You could also see DANCE later this month at the Joyce Theater in New York and the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago (this historic collaboration is also the subject of a current exhibit at The Whitney Museum).

The venue in Williamstown was auspicious, since the performances coincided with the recent opening of a 25-year installation of LeWitt's wall drawings, contained in three enormous galleries at Mass MoCA. Wandering through his works with no time constraints (they are voluminous and imposing, often running from floor to ceiling) it seemed I had stumbled on a key for better understanding Childs' choreography. (I saw it both nights that it was presented recently at Williams College and I will never forget the experience. At the end of the first show, I was starry-eyed and vertiginous; it seemed a spectacle beyond my comprehension. The second night I was better able to discern the structure and let my mind "inhabit" the work. Consequently, I consider it perhaps the greatest American dance of the late 20th century).

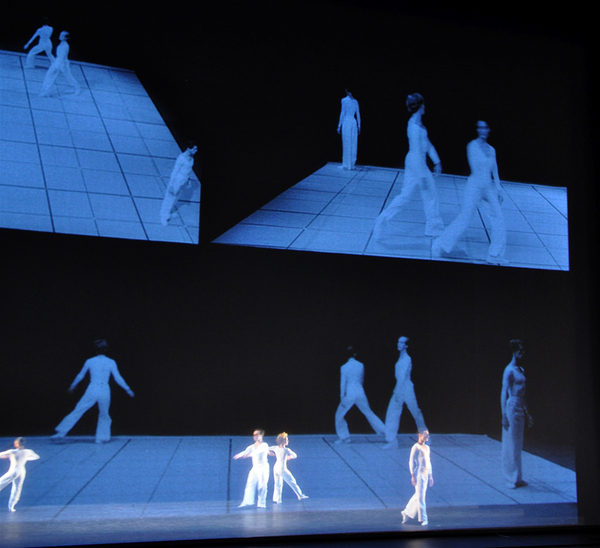

For his wall drawings, LeWitt worked often in combinative mode. He took "data sets" of lines or patterns and stated them in every possible pairing. The opening movement of DANCE is also for pairs of dancers, slightly staggered as they move always on a horizontal trajectory, until the element of a slight diagonal and subsequent direction change is introduced later on. They enter, cross the stage in gradually accumulating phrases of skips, hops, head tilts, and stay briefly in the air caught in a star shape, (think DaVinci's Vitruvian Man) and exit perhaps four to eight counts later. This happens again and again and again, until it feels like you are at the corner of an enormous field of activity and privy to only a glimpse of the full event. Yes, Childs' movement vocabulary is restrictive, but yet full of illusion. Like DaVinci, here LeWitt and Childs were involved in creating their own canons of proportion. LeWitt's black-and-white films for DANCE are exact recordings of the movement itself, a thrilling opportunity to see the original cast members.

- From Lucinda Childs’s DANCE. Image credit: Sally Cohn.

- From Lucinda Childs’s DANCE. Image credit: Sally Cohn.

- From a 1979 performance of Lucinda Childs’s DANCE. Image credit: Nathaniel Tileston.

"DANCE" was performed on September 25th at the '62 Center for Theatre, Williams College.

All images are courtesy of the Pomegranate Arts, Sally Cohn, and Nathaniel Tileston.