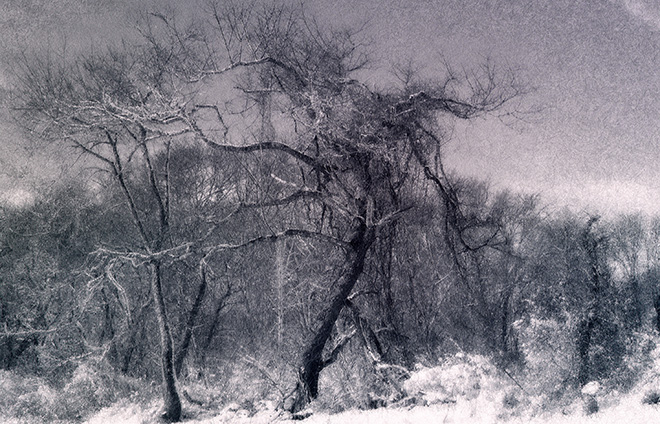

Great Neck Snow Tree, Harvey Goldman, 2013, archival digital print, 26"x36." Image courtesy of Harvey Goldman and Dedee Shattuck Gallery.

Great Neck Snow Tree, Harvey Goldman, 2013, archival digital print, 26"x36." Image courtesy of Harvey Goldman and Dedee Shattuck Gallery.Utilizing digital photography to carefully layer graphic elements of the natural world, Goldman’s images blurs the boundaries between still and moving images, painting and photography, realism and fantasy. These tensions form the basis of his Veiled Ancestors series, a body of work that originates from the vast catalogue of photographs that the artist has collected from his daily walks in the woods. Patches of lichen on the side of a tree, the vague outline of a fallen branch pressing through a thin sheet of snow, and the intersecting rings of mushrooms are all photographed and collected by the artist for their intimations of facial features or other intriguing formal qualities. Goldman spends extended periods of time staring into these images, attempting to isolate those patterns, textures or shapes that might be integrated into a larger whole. He then begins what he calls "improvising off the imagery," introducing symmetries around various patterns so that eyes, nose and mouth begin to appear. The process and the images it produce speak to the constructive power of vision, which in Goldman’s work is involved in constituting rather than passively reflecting the world.

Yet, as the firsthand experience of works such as Terra Vellum 03 attests, these works do not simply anthropomorphize nature by imposing a human face upon it. Rather, these faces seem to come out of the darkness and gaze at us of their own accord; they stare back. The effect for the viewer is of an encounter with something foreign and incomprehensible, despite the familiar spatial relations of the human face. In this, the series undoubtedly reflects the artist’s interest in African masks and tribal face painting, both of which center on transformation of the everyday into the extra-ordinary. More broadly, however, these works interrogate the tendency of images to present the natural world in terms of knowable conventions and recognizable forms. Nature is instead presented as wielding its own agency, one which operates and desires independent of the human sphere.

The wide arcs of history that the artist often evokes in his work are built into the processes by which Goldman’s images come into being. Indeed, if for Marey it was the visual richness of a single fleeting event which organized the image in linear fashion, for Goldman this operation works across larger expanses of time, unraveling the tidy narratives through which we tend to perceive nature. This is most evident in his Coincidentia Oppositorum series, which not only brings together disparate objects of the natural world, but conflicting seasons within a single frame, creating dynamic palimpsests that undercut the linearity of time. Coincidentia Oppositorum 02, for example, is organized graphically around a photograph of a sheet of melting ice that is shot through with holes as drops of rain break through its surface. As these cavernous hollows are superimposed upon what appears to be a late autumn scene, time loses its arrow. Winter is both ending and about to begin in the image as the camera is called upon not to suspend or freeze time but to expand its reach, accumulating multiple moments within its frame. The overall effect is somewhere between the enigmatic spirituality of Jerry Ueslmann’s photo-collages and those Romantic landscapes of Caspar David Friedrich or J.W.M. Turner which render the viewer’s relation to the natural world uncertain or tenuous.

Gratitude, Harvey Goldman, 2014, archival digital print, 36"x26." Image courtesy of Harvey Goldman and Dedee Shattuck Gallery.

Gratitude, Harvey Goldman, 2014, archival digital print, 36"x26." Image courtesy of Harvey Goldman and Dedee Shattuck Gallery.In his Extremities and Digits series, Goldman shifts gears a bit and interrogates the inner workings of his primary tool, the hand. Gratitude, for example, displays x-rays from the artist’s own hand at various stages of recovery after a recent surgery to treat carpal tunnel syndrome. The top registers are arranged so that images of the surgical views of the process mirror the lunar cycle below. The center panel of pointed arches crescendos with a triumphant fully-formed hand, which is both the subject and creator of the image. Despite never actually disclosing the artist himself, the work comprises a self-portrait of sorts. In the traditional of Rembrandt and Parmigianino, it is a meditation on the mystery of the creative process and the interconnectedness between the artist’s identity and his or her daily work.

The show’s pairing of Goldman’s early ceramic work with these digital composites draws out the artist’s enduring interest in texture and surface. Prone to firing his early pieces over a dozen times to create a three-dimensional surface of cracks, pinholes and pits (implied or actual), the artist’s photographs can be seen as continuing this practice in two dimensional form. For example, in his Great Snow Neck Tree series the branches of a tree reverberate through the frame, cracking the surface of the image with a fibrous network that emulates processes of "crazing" that result from excessive firing of pottery. As the photographic series is composed around the artist’s observation of a single tree over the period of three winters, these formal processes allow the processes of entropy and decay which envelop the tree to be written into the tactile surfaces of the image. Along with his Extremities and Digits series, these works oppose the recurring diagnosis of the digital as the engine behind a larger narrative of dematerialization and disconnect. Goldman’s deployment of this technology leads to a practice that is heavily grounded in physicality, tactility and gesture, even while it takes full advantage of the imaginative potential of the new medium.

The larger takeaway from this unique body of work is a defamiliarizing of the everyday, a way of opening up perception to textures, surfaces and processes which litter the visual landscape, but which often go unnoticed. In the hands of Goldman, these seemingly banal events and/or graphic features are imbued with an enigmatic presence, which force the viewer to keep looking.

The Apophenia: Harvey Goldman exhibition is on display at the Dedee Shattuck Gallery in Westport, MA through June 1. On May 24th, there will be a special screening of the Goldmans film Brahmanda at 2:00pm.